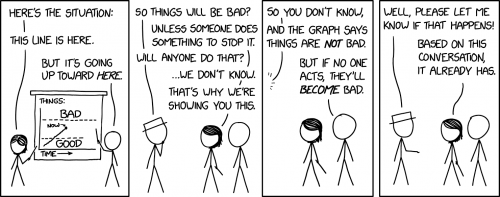

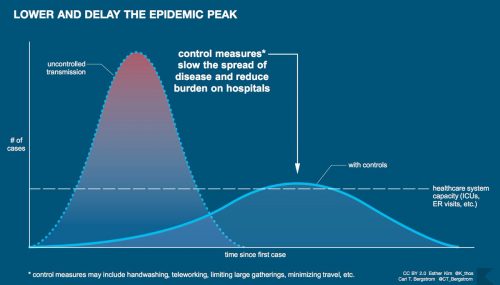

My university has closed all face-to-face classes until 1 April, when, I presume, they’ll reassess what should be done. I hope no one thinks everything will be over then, because it won’t be. We’re just getting started. I expect April is when the pandemic in the US will be just roaring into action.

40-70% of the US population will be infected over the next 12-18 months. After that level you can start to get herd immunity. Unlike flu this is entirely novel to humans, so there is no latent immunity in the global population.

[We used their numbers to work out a guesstimate of deaths— indicating about 1.5 million Americans may die. The panelists did not disagree with our estimate. This compares to seasonal flu’s average of 50K Americans per year. Assume 50% of US population, that’s 160M people infected. With 1% mortality rate that’s 1.6M Americans die over the next 12-18 months.]

The fatality rate is in the range of 10X flu.

This assumes no drug is found effective and made available.

The death rate varies hugely by age. Over age 80 the mortality rate could be 10-15%.

Don’t know whether COVID-19 is seasonal but if is and subsides over the summer, it is likely to roar back in fall as the 1918 flu did

There is no guarantee that this will be a replay of the 1918 pandemic, but we should prepare as if it is. I’m teaching cell biology in the fall, I’m going to spend the summer getting organized for possibly having to teach it online.

I hope that’s all I have to do, and we’re not going to end up preparing by digging trenches for mass graves.

This next recommendation is personally bothersome. My wife flew to Colorado before the extent of the crisis became unavoidably obvious. She was supposed to fly back next week. Flying is out of the question anymore, so we’ve been trying to come up with alternative methods of getting her back home.

We would say “Anyone over 60 stay at home unless it’s critical”. CDC toyed with idea of saying anyone over 60 not travel on commercial airlines.

Right now we’re considering that instead maybe she should stay in Boulder with my daughter for some indefinite period of time. Safety apart is smarter than travel together that maximizes our chance of infection.