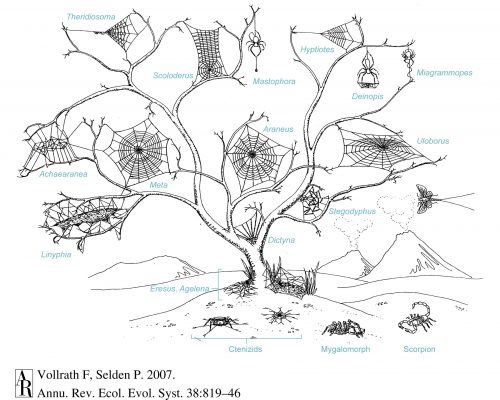

It’s been a while since I had anything new to report — the colony is just sitting there, waiting for me to provide the ladies with some males, since they ate all of them. But we’re gearing up for a field season, so there were a few things I was able to try.

I’ve written up a protocol for our summer spider survey. It’s mainly a series of steps we’re going to carry out as we scan a garage, because consistency is important. We’re not going to be able to see every spider in every place — they’re sneaky, quiet little buggers — so we need to survey each environment in the same way, so that we can compare the residences, even if we know we’re going to miss animals. So Mary and I put on headlamps, plunged into our frigid garage and went through the motions to see how practical my plan was.

We didn’t expect much. It’s been a hard winter, and while today felt much warmer and the snow is melting, it really is still only 2°C, hardly happy weather for spiders, and not any better for their prey. We went spider hunting anyway.

As expected, there wasn’t much alive out there, maybe. The only spiders we saw were cellar spiders, Pholcidae, and they didn’t seem to be up to much. In fact, they might have all been dead. They were all inert and unresponsive to touch, but were still strangely plump and life-like, if still. They could be little frozen corpsicles, or possibly estivating. We couldn’t tell. We counted them anyway, if they looked intact and like, maybe, they’re going to rise from the dead at some point. It was all practicing the protocol, anyway.

The end result is that our cold and unpleasant and rather cluttered garage, 5.3m wide and 6.1m deep, has walls that are all covered with cobwebs, especially any part of the wall that is more than just a bare surface. If there was so much as a nail sticking out of a sheet of fiberboard, there was a cobweb on it. We counted a total of 63 zombie pholcids in that little space, and also found 11 egg cases of at least 3 different types. We’re starting to think our biggest challenge will be counting all the spiders in a reasonable amount of time once summer arrives with the mosquito season and the happy little beasts start fornicating fiercely.

One neat little surprise: along a back wall, there’s an area with a rack of shallow shelves, and Mary excitedly tells me that she has discovered spiderlings! I was skeptical and thought that was metabolically improbable given the ambient temperatures, but when I looked, sure enough, there were sheets of webbing in all of those shelves, and in all of them there was an explosion of tiny white dots with itty-bitty hairlike protrusions. They were of the right size, and that was the kind of scattering I’ve seen in newly hatched spiders in the lab, but I couldn’t imagine they might have survived a Minnesota winter, and they didn’t.

I twirled a patch of cobweb with the putative spiderlings onto a brush, and brought it into the lab, and sure enough…spiderlings. Well, the molted cuticles of many adorable baby spiders. Here’s a photo.