Trivia fact: Edgar Rice Burroughs, in addition to his Tarzan and Mars books, also wrote a handful of pulp stories about Venus, which was called Amtor by the natives, and his intrepid hero, Carson Napier. They were a little different from the Mars series, where John Carter was teleported to Mars by some form of astral projection, in that Napier was a rocket pilot flying to Mars who made a tiny error in his calculation and crash-landed on Venus instead. Then it lapses into the usual formulaic adventure story where Napier finds a Princess (there’s always a princess), falls in love, and the two of them bumble about needing to rescue each other from pirates and communists. Amtor, by the way, is covered by oceans and continents of giant trees, and the cloud cover keeps the planet cool and liveable, except when the clouds briefly break and a brutal sun sets everything on fire beneath the gap.

Unfortunately, the real Venus has surface temperatures of 450°C and a dense and acidic atmosphere. Nothing lives there.

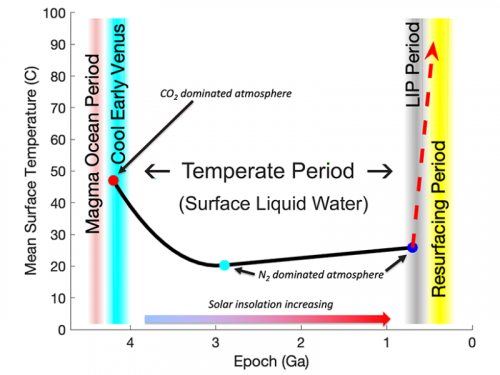

This recent modeling of the Venerian atmosphere suggests that there may have been a long period of relative coolth in the planet’s history. The runaway greenhouse effect wouldn’t have occurred until a period of intense volcanic activity that produced LIPs, Large Igneous Provinces, released even more CO2, and then the temperatures soared.

That surge occurred less than a billion years ago, so it’s easy to imagine warm (mean temperature of around ~20°C, compared to Earth’s current ~15°C) oceans in which life could have evolved before global warming slammed the hammer down and burnt the soup.

I think Carson Napier’s navigation error had to have been off by more than I thought: 150 million kilometers and a billion years. Even then he wouldn’t have found princesses, but at best the equivalent of single-celled prokaryotes, which would have been far more interesting than mere Amtorian princesses.