In my development class, students have been blogging away for the last few weeks, and I asked them to send me links to ones they wouldn’t mind seeing advertised. I’ve told them that an important part of effectively blogging is to link and comment, so they’re supposed to write something this week that adds to one of these posts and links to it on their own blog, and they’re also supposed to leave a comment on their fellow students’ work.

I warned them too that I’d highlight these publicly and urge my readers to look and say a few things: so go ahead and comment, criticize, praise, whatever — I told them that the good will come with the bad.

I suspect I’ll have to explain to them how to kill spam and remove irrelevant or outrageous comments in the next class…

-

Our gross observations of nematode worms.

-

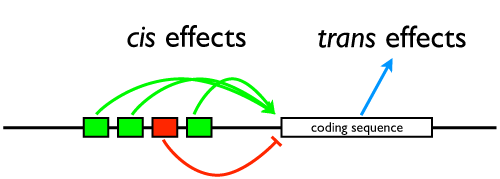

The concepts of mosaicism vs. regulation.

-

The concept of morphogens, specifically decapentaplegic.

-

The lab is a lot of photomicrography, and sometimes making photomontages is useful.

-

Spectacular gynandromorphy.