Blood is life, you know. That’s been the lesson from science documentaries like Dracula and Mad Max: Fury Road.

Remember creepy weird Bryan Johnson, the middle-aged Silicon Valley techbro who want to live forever by gobbling down lots of supplements, slathering on the skin creams, and eating a strangely specific diet? Now he has decided that vampirism is the answer.

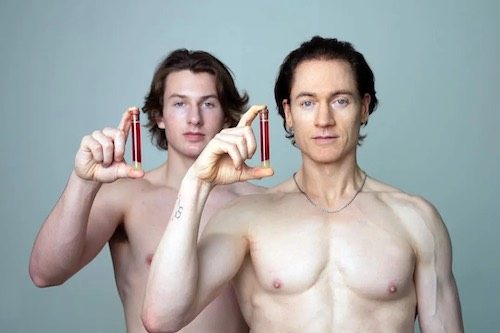

An anti-aging zealot who spends $2 million a year in a quest to turn back time has dragged his teenage son into being his personal “blood boy.”

Bryan Johnson, the 45-year-old tech tycoon who wants to keep his internal organs, including his penis and rectum, functioning youthfully — enlisted 17-year-old Talmage to provide blood transfusions, Bloomberg reported on Monday.

At a clinic near Dallas last month, Johnson, his 70-year-old dad, Richard, and Talmage showed up for an hours-long, tri-generational blood-swapping treatment, the outlet reported.

Johnson usually receives plasma from an anonymous donor, but this time Talmage provided a liter of his blood, which was converted into batches of piece parts — a batch of liquid plasma and another of red and white blood cells and platelets.

Ugh. This is creepy child abuse — although they did it in Texas, where they hate children, so he’ll probably get away with it. Even if this worked, I wouldn’t ask my children to ever do this for me.

I also notice the icky Elizabeth Holmes-style pose. It’s all quackery.