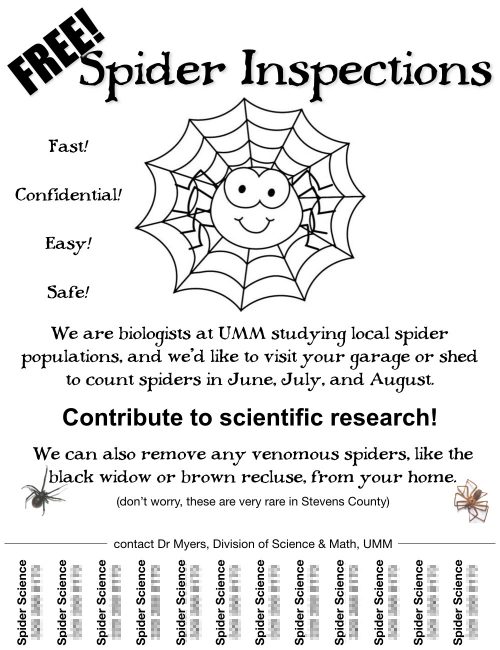

I survived my first day of field work, although right now I’m feeling every square millimeter of my left trapezius muscle — all that stooping and stretching and poking exacerbated all my existing aches and pains. Also, it was hot, up around 30°C, which I think is the major limiting factor in how long we can keep it up. Did you know that most people don’t have air-conditioned garages? It’s true!

We surveyed half a dozen houses, which is what I hoped we could accomplish, so we’re right on track. I’m hoping to reach around 30 houses this week. There’s not much we can say from such a preliminary sample, but we have a couple of suggestive observations. The older the house, the more spiders. The most heavily populated garage had 37 active spiders on the walls, and 17 egg cases — we’re looking forward to seeing the population explosion there next month. The most sparsely populated had 1.

Almost all the spiders were either Pholcidae or Theridiidae, and curiously, their numbers were inversely correlated to one another. It could be a sign of a competitive interaction, or some subtle detail in the environment of these buildings that favors one over the other. Or it could just be our tiny sample size so far. We found only three spiders total that didn’t belong to those two families — I have to key them out this evening.

I also have to plug all the data into the computer, too. I’m practicing a little data security: there’s one key sheet with the addresses and a code, and then the data for each house is stored in paper files under that code, and also recorded in a database. I didn’t know if that would be necessary, but two people asked me if we’d keep the numbers confidential — I guess there’s some concern that one doesn’t want one’s home known as spider-infested. I would think that would increase the property value, but that’s just me.

Now I have to recover over night, and do it again tomorrow and the day after. Sunday shall be a day of rest, sort of. I’ve got about 30 spiders in the colony that will need some TLC that day.

Look at this beautiful beast! You’re missing out if you aren’t on our spider survey.