I think the title is a double entendre in Australian, but it’s not a language I am fluent in. Anyway, a paper in Nature describes an assortment of organisms found in amber from Australia and New Zealand, ranging in age from 230 million years to 40 million years. It’s lovely stuff.

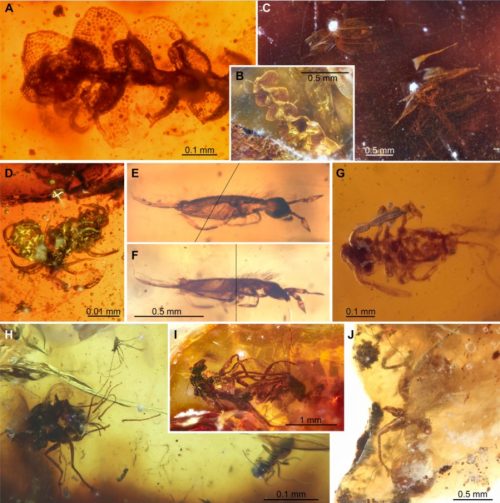

Significant bioinclusions of plants and animals in Southern Gondwana late middle Eocene amber of Anglesea, Victoria. (A to B) Liverworts of the genus Radula (Marchantiophyta: Radulaceae). (C) Two stems with perfectly preserved phyllids or leaf-like structures of mosses of the genus Racopilum (Bryophyta: Racopilaceae). (D) Juvenile individuals of spiders. (E to F) Springtail of the living genus Coecobrya (Entomobryomorpha: Entomobryidae) in two views. (G) A Symphypleona springtail. (H) Light photograph of large piece of yellow amber with two dipterans, Dolichopodidae at left and Ceratopogonidae at right, and at top of image a mite of the living genus Leptus (Arachnida: Acari: Trombidiformes: Erythraeidae). (I) Dipterans of the family Dolichopodidae (long-legged flies) in copula. (J) Worker ant of the living genus Monomorium or a “Monomorium-like” lineage (Hymenoptera: Formicoidea: Formicidae).

I don’t know about you, but I was most interested in D, the two juvenile spiders.

Wait, I do know about you — you’re most interested in I, the two flies caught in the act. So here’s a closeup.

Count yourself lucky. Now if you want to take a pornographic selfie, you just whip out your phone, capture the moment, and go on with your life. Forty million years ago, you had to say “Freeze! Look sexy!” and wait for a drop of sap to ooze over you, and then you had to hold the pose for tens of millions of years.