(via Loire Nature)

(Also on Sb)

Earlier, when I made that point about the limitations of what we can see, touch, hear, and smell, I sure wish I’d seen this cartoon, because I would have used it.

Baby lobsters are far more adorable than kittens!

I am currently staying at my daughter’s house, where our former cat Midnight now lives. There may be some epic battles today, which he will win by peeing on me.

(via Aquaviews)

One of the bonuses of having lots of legs is that you can go bipedal whenever you feel like it.

(via TONMO)

A fun suggestion: do a google image search for “Wonderpus”. Be prepared to go blind.

(Also on Sb)

Usually, first thing in the morning, I’m feeding you some fresh new outrage or foolishness. How about something to awe and inspire for once? Here, watch the gorillas, and think about your place in the universe.

(Also on Sb)

Menstruation is a peculiar phenomenon that women go through on a roughly monthly cycle, and it’s not immediately obvious from an evolutionary standpoint why they do it. It’s wasteful — they are throwing away a substantial amount of blood and tissue. It seems hazardous; ancestrally, in a world full of predators and disease, leaving a blood trail or filling a delicate orifice with dying tissue seems like a bad idea. And as many women can tell you, it’s uncomfortable, awkward, and sometimes debilitating. So why, evolution, why?

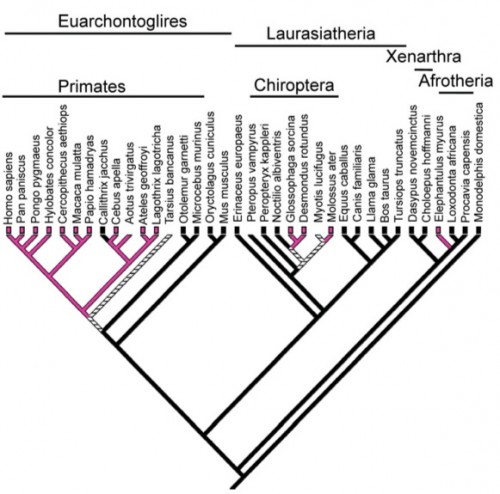

One assumption some people might make is that that is just the way mammalian reproduction works. This isn’t true! Most mammals do not menstruate — they do not cycle their uterine linings, but instead only build up a thickened endometrium if fertilization occurs, which looks much more efficient. Of the mammals, only most primates, a few bats, and elephant shrews are among the lucky animals that menstruate, and as you can see from the phylogeny, the scattered diversity of menstruating mammals implies that the trait was not present ancestrally — we primates acquired it relatively late.

Phylogeny showing the distribution of menstruation in placental mammals and the inferred states of ancestral lineages. Menstruating species/lineages are colored in pink, non- menstruating species/lineages in black. Species in which the character state is not known are not colored, and lineages of equivocal state are represented with black lines. Monodelphis represents the outgroup. Inference of ancestral states was performed in MacClade 4 by the parsimony method. Note that there is strong evidence for three independent originations of menstruation among placental mammals.

I suppose we could blame The Curse on The Fall, but then this phylogeny would suggest that Adam and Eve were part of a population of squirrel-like proto-primates living in the early Paleocene. That’s rather unbiblical, though, and what did the bats and elephant shrews do to deserve this?

There are many explanations floating around. One is that it’s a way to flush out nasty pathogens injected into the reproductive tract by ejaculating males — but that phenomenon is ubiquitous, so you have to wonder why only a few species bother. Another explanation is that it’s more efficient to get rid of the endometrium when not using it, than to maintain it indefinitely; but this is a false distinction, because other mammals don’t maintain the endometrium, they just build it up in response to fertilization. And finally, another reason is that humans have rather agressive embryos that implant deeply and intimately with the mother’s tissues, and menstruation “preconditions” the uterine lining to cope with the stress. There is, unfortunately, no evidence that menstruation provides any boost to the ‘toughness’ of the uterus at all.

A new paper by Emera, Romero, and Wagner suggests an interesting new idea. They turn the question around: menstruation isn’t the phenomenon to be explained, decidualization, the production of a thickened endometrial lining, is the key process.

All mammals prepare a specialized membrane for embryo implantation, the difference is that most mammals exhibit triggered decidualization, where the fertilized embryo itself instigates the thickening, while most primates have spontaneous decidualization (SD), which occurs even in the absence of a fertilized embryo. You can, for instance, induce menstruation in mice. By scratching the mouse endometrium, they will go through a pseudopregnancy and build up a thickened endometrial lining that will be shed when progesterone levels drop. So the reason mice don’t menstruate isn’t that they lack a mechanism for shedding the endometrial lining…it’s that they don’t build it up in the first place unless they’re actually going to use it.

So the question is, why do humans have spontaneous decidualization?

The answer that Emera suggests is entirely evolutionary, and involves maternal-fetal conflict. The mother and fetus have an adversarial relationship: mom’s best interest is to survive pregnancy to bear children again, and so her body tries to conserve resources for the long haul. The fetus, on the other hand, benefits from wresting as much from mom as it can, sometimes to the mother’s detriment. The fetus, for instance, manipulates the mother’s hormones to weaken the insulin response, so less sugar is taken up by mom’s cells, making more available for the fetus.

Within the mammals, there is variation in how deeply the fetus sinks its placental teeth into the uterus. Some species are epithelochorial; the connection is entirely superficial. Others are endotheliochorial, in which the placenta pierces the uterine epithelium. And others, the most invasive, are hemochorial, and actually breach maternal blood vessels. Humans are hemochorial. All of the mammalian species that menstruate are also hemochorial.

That’s a hint. Menstruation is a consequence of self-defense. Females build up that thickened uterine lining to protect and insulate themselves from the greedy embryo and its selfish placenta. In species with especially invasive embryos, it’s too late to wait for the moment of implantation — instead, they build up the wall pre-emptively, before and in case of fertilization. Then, if fertilization doesn’t occur, the universal process of responding to declining progesterone levels by sloughing off the lining occurs.

Bonus! Another process that goes on is that the lining of the uterus is also a sensor for fetal quality, detecting chromosomal abnormalities and allowing them to be spontaneously aborted early. There is some evidence for this: women vary in their degree of decidualization, and women with reduced decidualization have been found to become pregnant more often, but also exhibit pregnancy failure more often. So having a prepared uterus not only helps to fend off overly-aggressive fetuses, it allows mom a greater ability to be selective in which fetuses she carries to term.

The authors also have a proposed mechanism for how menstruation could have evolved, and it involves genetic assimilation. Genetic assimilation is a process which begins with an environmentally induced phenotype (in this case, decidualization in response to implantation), which is then strengthened by genetic mutations that stabilize the phenotype — phenotype first, followed by selection for the mutations that reinforce the phenotype. They make predictions from this hypothesis. In species that don’t undergo SD, embryo implantation triggers an elevation of cyclic AMP in the endometrium that causes growth of the lining. If genetic assimilation occurred, they predict that what happened in species with SD was the novel coupling of hormonal signaling to the extant activation process.

If either of these models were correct, we would expect an upregulation of cAMP- stimulating agents in response to pro- gesterone in menstruating species like humans, but not in non-menstruating species such as the mouse.

Results from experiments like those described above will elucidate the evolutionary pathway from induced to spontaneous decidualization, allowing us to answer long-unanswered questions about the evolutionary significance of menstruation. In addition, they will provide mechanistic insights that might be useful in the treatment of common reproductive disorders such as endometriosis, endometrial cancer, preeclampsia, and recurrent pregnancy loss. These disorders involve dysfunctional endometrial responses during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Thus, clarifying mechanisms of the normal endometrial response to maternal hormones, i.e. SD, will facilitate identification of genes with abnormal function in women with these disorders. An analysis of how SD came about in evolution can aid in identifying these critical molecular mechanisms.

Evolution, genetic assimilation, a prediction from an evolutionary hypothesis, and significant biomedical applications … that all sounds powerful to me.

Emera D, Romero R, Wagner G (2011) The evolution of menstruation: A new model for genetic assimilation: Explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness. Bioessays 34(1):26-35.

(Also on FtB)

Menstruation is a peculiar phenomenon that women go through on a roughly monthly cycle, and it’s not immediately obvious from an evolutionary standpoint why they do it. It’s wasteful — they are throwing away a substantial amount of blood and tissue. It seems hazardous; ancestrally, in a world full of predators and disease, leaving a blood trail or filling a delicate orifice with dying tissue seems like a bad idea. And as many women can tell you, it’s uncomfortable, awkward, and sometimes debilitating. So why, evolution, why?

One assumption some people might make is that that is just the way mammalian reproduction works. This isn’t true! Most mammals do not menstruate — they do not cycle their uterine linings, but instead only build up a thickened endometrium if fertilization occurs, which looks much more efficient. Of the mammals, only most primates, a few bats, and elephant shrews are among the lucky animals that menstruate, and as you can see from the phylogeny, the scattered diversity of menstruating mammals implies that the trait was not present ancestrally — we primates acquired it relatively late.

I suppose we could blame The Curse on The Fall, but then this phylogeny would suggest that Adam and Eve were part of a population of squirrel-like proto-primates living in the early Paleocene. That’s rather unbiblical, though, and what did the bats and elephant shrews do to deserve this?

There are many explanations floating around. One is that it’s a way to flush out nasty pathogens injected into the reproductive tract by ejaculating males — but that phenomenon is ubiquitous, so you have to wonder why only a few species bother. Another explanation is that it’s more efficient to get rid of the endometrium when not using it, than to maintain it indefinitely; but this is a false distinction, because other mammals don’t maintain the endometrium, they just build it up in response to fertilization. And finally, another reason is that humans have rather agressive embryos that implant deeply and intimately with the mother’s tissues, and menstruation “preconditions” the uterine lining to cope with the stress. There is, unfortunately, no evidence that menstruation provides any boost to the ‘toughness’ of the uterus at all.

A new paper by Emera, Romero, and Wagner suggests an interesting new idea. They turn the question around: menstruation isn’t the phenomenon to be explained, decidualization, the production of a thickened endometrial lining, is the key process.

All mammals prepare a specialized membrane for embryo implantation, the difference is that most mammals exhibit triggered decidualization, where the fertilized embryo itself instigates the thickening, while most primates have spontaneous decidualization (SD), which occurs even in the absence of a fertilized embryo. You can, for instance, induce menstruation in mice. By scratching the mouse endometrium, they will go through a pseudopregnancy and build up a thickened endometrial lining that will be shed when progesterone levels drop. So the reason mice don’t menstruate isn’t that they lack a mechanism for shedding the endometrial lining…it’s that they don’t build it up in the first place unless they’re actually going to use it.

So the question is, why do humans have spontaneous decidualization?

The answer that Emera suggests is entirely evolutionary, and involves maternal-fetal conflict. The mother and fetus have an adversarial relationship: mom’s best interest is to survive pregnancy to bear children again, and so her body tries to conserve resources for the long haul. The fetus, on the other hand, benefits from wresting as much from mom as it can, sometimes to the mother’s detriment. The fetus, for instance, manipulates the mother’s hormones to weaken the insulin response, so less sugar is taken up by mom’s cells, making more available for the fetus.

Within the mammals, there is variation in how deeply the fetus sinks its placental teeth into the uterus. Some species are epithelochorial; the connection is entirely superficial. Others are endotheliochorial, in which the placenta pierces the uterine epithelium. And others, the most invasive, are hemochorial, and actually breach maternal blood vessels. Humans are hemochorial. All of the mammalian species that menstruate are also hemochorial.

That’s a hint. Menstruation is a consequence of self-defense. Females build up that thickened uterine lining to protect and insulate themselves from the greedy embryo and its selfish placenta. In species with especially invasive embryos, it’s too late to wait for the moment of implantation — instead, they build up the wall pre-emptively, before and in case of fertilization. Then, if fertilization doesn’t occur, the universal process of responding to declining progesterone levels by sloughing off the lining occurs.

Bonus! Another process that goes on is that the lining of the uterus is also a sensor for fetal quality, detecting chromosomal abnormalities and allowing them to be spontaneously aborted early. There is some evidence for this: women vary in their degree of decidualization, and women with reduced decidualization have been found to become pregnant more often, but also exhibit pregnancy failure more often. So having a prepared uterus not only helps to fend off overly-aggressive fetuses, it allows mom a greater ability to be selective in which fetuses she carries to term.

The authors also have a proposed mechanism for how menstruation could have evolved, and it involves genetic assimilation. Genetic assimilation is a process which begins with an environmentally induced phenotype (in this case, decidualization in response to implantation), which is then strengthened by genetic mutations that stabilize the phenotype — phenotype first, followed by selection for the mutations that reinforce the phenotype. They make predictions from this hypothesis. In species that don’t undergo SD, embryo implantation triggers an elevation of cyclic AMP in the endometrium that causes growth of the lining. If genetic assimilation occurred, they predict that what happened in species with SD was the novel coupling of hormonal signaling to the extant activation process.

If either of these models were correct, we would expect an upregulation of cAMP- stimulating agents in response to pro- gesterone in menstruating species like humans, but not in non-menstruating species such as the mouse.

Results from experiments like those described above will elucidate the evolutionary pathway from induced to spontaneous decidualization, allowing us to answer long-unanswered questions about the evolutionary significance of menstruation. In addition, they will provide mechanistic insights that might be useful in the treatment of common reproductive disorders such as endometriosis, endometrial cancer, preeclampsia, and recurrent pregnancy loss. These disorders involve dysfunctional endometrial responses during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Thus, clarifying mechanisms of the normal endometrial response to maternal hormones, i.e. SD, will facilitate identification of genes with abnormal function in women with these disorders. An analysis of how SD came about in evolution can aid in identifying these critical molecular mechanisms.

Evolution, genetic assimilation, a prediction from an evolutionary hypothesis, and significant biomedical applications … that all sounds powerful to me.

Emera D, Romero R, Wagner G (2011) The evolution of menstruation: A new model for genetic assimilation: Explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness. Bioessays 34(1):26-35.

(Also on Sb)

P.S. The maternal-fetal conflict is also a conflict between males and females: it is in the man’s reproductive interests to have his genes propagated in any one pregnancy, while it is in the woman’s reproductive interests to bail out and try again if conditions aren’t optimal for any one pregnancy. This conflict is also played out in culture, as well as genetics — pro-choice is a pro-woman strategy, anti-abortion is a pro-man position. Sometimes, politics is a reflection of an evolutionary struggle, too.

How appropriate that one of the symbols of the season should be a parasite.

(Also on Sb)