You’d think with all those arms they’d have at least one free to focus and set the exposure. This is a picture taken by an octopus who stole a divers’ camera.

The diver chased it and got the camera back. Otherwise, we’d be waiting for the octopus to get online and upload the pictures to youtube.

I rarely laugh out loud when reading science papers, but sometimes one comes along that triggers the response automatically. Although, in this case, it wasn’t so much a belly laugh as an evil chortle, and an occasional grim snicker. Dan Graur and his colleagues have written a rebuttal to the claims of the ENCODE research consortium — the group that claimed to have identified function in 80% of the genome, but actually discovered that a formula of 80% hype gets you the attention of the world press. It was a sad event: a huge amount of work on analyzing the genome by hundreds of labs got sidetracked by a few clueless statements made up front in the primary paper, making it look like they were led by ignoramuses who had no conception of the biology behind their project.

Now Graur and friends haven’t just poked a hole in the balloon, they’ve set it on fire (the humanity!), pissed on the ashes, and dumped them in a cesspit. At times it feels a bit…excessive, you know, but still, they make some very strong arguments. And look, you can read the whole article, On the immortality of television sets: “function” in the human genome according to the evolution-free gospel of ENCODE, for free — it’s open source. So I’ll just mention a few of the highlights.

I’d originally criticized it because the ENCODE argument was patently ridiculous. Their claim to have assigned ‘function’ to 80% (and Ewan Birney even expected it to converge on 100%) of the genome boiled down to this:

The vast majority (80.4%) of the human genome participates in at least one biochemical RNA- and/or chromatin-associated event in at least one cell type.

So if ever a transcription factor ever, in any cell, bound however briefly to a stretch of DNA, they declared it to be functional. That’s nonsense. The activity of the cell is biochemical: it’s stochastic. Individual proteins will adhere to any isolated stretch of DNA that might have a sequence that matches a binding pocket, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that the constellation of enhancers and promoters are present and that the whole weight of the transcriptional machinery will regularly operate there. This is a noisy system.

The Graur paper rips into the ENCODE interpretations on many other grounds, however. Here’s the abstract to give you a summary of the violations of logic and evidence that ENCODE made, and also to give you a taste of the snark level in the rest of the paper.

A recent slew of ENCODE Consortium publications, specifically the article signed by all Consortium members, put forward the idea that more than 80% of the human genome is functional. This claim flies in the face of current estimates according to which the fraction of the genome that is evolutionarily conserved through purifying selection is under 10%. Thus, according to the ENCODE Consortium, a biological function can be maintained indefinitely without selection, which implies that at least 80 − 10 = 70% of the genome is perfectly invulnerable to deleterious mutations, either because no mutation can ever occur in these “functional” regions, or because no mutation in these regions can ever be deleterious. This absurd conclusion was reached through various means, chiefly (1) by employing the seldom used “causal role” definition of biological function and then applying it inconsistently to different biochemical properties, (2) by committing a logical fallacy known as “affirming the consequent,” (3) by failing to appreciate the crucial difference between “junk DNA” and “garbage DNA,” (4) by using analytical methods that yield biased errors and inflate estimates of functionality, (5) by favoring statistical sensitivity over specificity, and (6) by emphasizing statistical significance rather than the magnitude of the effect. Here, we detail the many logical and methodological transgressions involved in assigning functionality to almost every nucleotide in the human genome. The ENCODE results were predicted by one of its authors to necessitate the rewriting of textbooks. We agree, many textbooks dealing with marketing, mass-media hype, and public relations may well have to be rewritten.

You may be wondering about the curious title of the paper and its reference to immortal televisions. That comes from (1): that function has to be defined in a context, and that the only reasonable context for a gene sequence is to identify its contribution to evolutionary fitness.

The causal role concept of function can lead to bizarre outcomes in the biological sciences. For example, while the selected effect function of the heart can be stated unambiguously to be the pumping of blood, the heart may be assigned many additional causal role functions, such as adding 300 grams to body weight, producing sounds, and preventing the pericardium from deflating onto itself. As a result, most biologists use the selected effect concept of function, following the Dobzhanskyan dictum according to which biological sense can only be derived from evolutionary context.

The ENCODE group could only declare function for a sequence by ignoring all other context than the local and immediate effect of a chemical interaction — it was the work of short-sighted chemists who grind the organism into slime, or worse yet, only see it as a set of bits in a highly reduced form in a computer database.

From an evolutionary viewpoint, a function can be assigned to a DNA sequence if and only if it is possible to destroy it. All functional entities in the universe can be rendered nonfunctional by the ravages of time, entropy, mutation, and what have you. Unless a genomic functionality is actively protected by selection, it will accumulate deleterious mutations and will cease to be functional. The absurd alternative, which unfortunately was adopted by ENCODE, is to assume that no deleterious mutations can ever occur in the regions they have deemed to be functional. Such an assumption is akin to claiming that a television set left on and unattended will still be in working condition after a million years because no natural events, such as rust, erosion, static electricity, and earthquakes can affect it. The convoluted rationale for the decision to discard evolutionary conservation and constraint as the arbiters of functionality put forward by a lead ENCODE author (Stamatoyannopoulos 2012) is groundless and self-serving.

There is a lot of very useful material in the rest of the paper — in particular, if you’re not familiar with this stuff, it’s a very good primer in elementary genomics. The subtext here is that there are some dunces at ENCODE who need to be sat down and taught the basics of their field. I am not by any means a genomics expert, but I know enough to be embarrassed (and cruelly amused) at the dressing down being given.

One thing in particular leapt out at me is particularly fundamental and insightful, though. A common theme in these kinds of studies is the compromise between sensitivity and selectivity, between false positives and false negatives, between Type II and Type I errors. This isn’t just a failure to understand basic biology and biochemistry, but incomprehension about basic statistics.

At this point, we must ask ourselves, what is the aim of ENCODE: Is it to identify every possible functional element at the expense of increasing the number of elements that are falsely identified as functional? Or is it to create a list of functional elements that is as free of false positives as possible. If the former, then sensitivity should be favored over selectivity; if the latter then selectivity should be favored over sensitivity. ENCODE chose to bias its results by excessively favoring sensitivity over specificity. In fact, they could have saved millions of dollars and many thousands of research hours by ignoring selectivity altogether, and proclaiming a priori that 100% of the genome is functional. Not one functional element would have been missed by using this procedure.

This is a huge problem in ENCODE’s work. Reading Birney’s commentary on the process, you get a clear impression that they regarded it as a triumph every time they got even the slightest hint that a stretch of DNA might be bound by some protein — they were terribly uncritical and grasped at the feeblest straws to rationalize ‘function’ everywhere they looked. They wanted everything to be functional, and rather than taking the critical scientific view of trying to disprove their own claims, they went wild and accepted every feeble excuse to justify them.

The Intelligent Design creationists get a shout-out — they’ll be pleased and claim it confirms the validity of their contributions to real science. Unfortunately for the IDiots, it is not a kind mention, but a flat rejection.

We urge biologists not be afraid of junk DNA. The only people that should be afraid are those claiming that natural processes are insufficient to explain life and that evolutionary theory should be supplemented or supplanted by an intelligent designer (e.g., Dembski 1998; Wells 2004). ENCODE’s take-home message that everything has a function implies purpose, and purpose is the only thing that evolution cannot provide. Needless to say, in light of our investigation of the ENCODE publication, it is safe to state that the news concerning the death of “junk DNA” have been greatly exaggerated.

Another interesting point is the contrast between big science and small science. As a microscopically tiny science guy, getting by on a shoestring budget and undergraduate assistance, I like this summary.

The Editor-in-Chief of Science, Bruce Alberts, has recently expressed concern about the future of “small science,” given that ENCODE-style Big Science grabs the headlines that decision makers so dearly love (Alberts 2012). Actually, the main function of Big Science is to generate massive amounts of reliable and easily accessible data. The road from data to wisdom is quite long and convoluted (Royar 1994). Insight, understanding, and scientific progress are generally achieved by “small science.” The Human Genome Project is a marvelous example of “big science,” as are the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (Abazajian et al. 2009) and the Tree of Life Web Project (Maddison et al. 2007).

Probably the most controversial part of the paper, though, is that the authors conclude that ENCODE fails as a provider of Big Science.

Unfortunately, the ENCODE data are neither easily accessible nor very useful—without ENCODE, researchers would have had to examine 3.5 billion nucleotides in search of function, with ENCODE, they would have to sift through 2.7 billion nucleotides. ENCODE’s biggest scientific sin was not being satisfied with its role as data provider; it assumed the small-science role of interpreter of the data, thereby performing a kind of textual hermeneutics on a 3.5-billion-long DNA text. Unfortunately, ENCODE disregarded the rules of scientific interpretation and adopted a position common to many types of theological hermeneutics, whereby every letter in a text is assumed a priori to have a meaning.

Ouch. Did he just compare ENCODE to theology? Yes, he did. Which also explains why the Intelligent Design creationists are so happy with its bogus conclusions.

How is it, living in the Anthropocene?

Sea levels will likely rise a few feet by the year 2100. Current fish wet biomass is about 2 billion tons, so removing them won’t make a dent either. (Marine fish biomass dropped by 80% over the last century, which—taking into consideration the growth rate of the world’s shipping fleet—leads to an odd conclusion: Sometime in the last few years, we reached a point where there are, by weight, more ships in the ocean than fish.)

The current world shipping fleet has a displacement of about 2.15 billion tons (most of which is oil and ore), so yeah, we humans are now bulking out more volume in the oceans than the fish do (we’ve got a long ways to go before we overtake invertebrates and bacteria, I suspect).

The other depressing point in the article is that global warming is adding more water to the oceans every second, and that every 16 hours we’re adding more than that 2 billion tons of water to the ocean.

I like reading David Roberts’ stuff on Grist, especially when I disagree with him. Sadly, there’s not a thing I disagree with in this piece rebutting Andrew Revkin on opposition to Keystone. (Perhaps excepting his characterization of Matt Nisbet as a “professional wanker,” which I find overly generous given that I have always found Nisbet sorely lacking in professionalism.)

This weekend, close to 50,000 people gathered for the biggest rally ever against climate change, a threat Revkin acknowledges is enormous, difficult, and urgent. Revkin and his council of wonks took to Twitter to argue that the rally and the campaign behind it are misdirected, absolutist, confused, and bereft of long-term strategy. They had this familiar conversation as the rally was unfolding.

As a result, Revkin suffered the grievous injury of a frustrated tweet from Wen Stephenson, a journalist who has crossed over to activism. This gave the wounded Revkin the opportunity to write yet another lament on the slings and arrows that face the Reasonable Man. He faced down the scourge of single-minded “my way or the highway environmentalism,” y’all, but don’t worry, he’s got a thick skin. He lived to tell the tale.

This is all for the benefit of an elite audience, mind you, for whom getting yelled at by activists is the sine qua non of seriousness. The only thing that boosts VSP cred more is getting yelled at by activists on Both Sides.

Nice line, that last one. Useful in SO many contexts.

Roberts’ casual slam against the Frameinator comes in response to this tweet, in which Nisbet chides 350.org types for not hewing to his own special brand of 13-dimensional chess:

@globalecoguy @revkin @levi_m @philaroneanu @350 Strategy distracts, limits ability for Obama et al to broker path forward, even w/ Dems.

— Matthew C. Nisbet (@MCNisbet) February 18, 2013

What struck me about the thread that tweet came in was the overwhelming criticism of Keystone pipeline opponents for not having an overarching strategy that extends past stopping the Keystone pipeline as they mobilize people to oppose the Keystone pipeline. That criticism isn’t quite true: 350.org, for instance, is full of local student groups putting pressure on their colleges to divest from fossil fuel companies, in much the same fashion as the anti-apartheid divestment movement that hit U.S. campuses in the 1980s.

But there’s also an uncanny similarity between the objections voiced in that thread to Keystone opponents’ lack of a formal program, and objections we heard to the Occupy Wall Street folks way back in 2011. We heard back then that because OWS didn’t have, say, a 13-point program to adjust the schedule of lunches at quarterly SEC hearings, that they weren’t Very Serious People.

Which, of course, essentially translates to “your genuine groundswell of concern and subsequent activism threatens to undermine our position as experts.”

I used to get lots of letters and emails when I worked at Earth Island Institute from helpful people who thought somebody ought to start a campaign to do something. That something varied: take on the issue of overpopulation, plant redwood trees along the shore of San Francisco Bay, teach inner city children about marmots, whatever. The problem was that very few of these missives were phrased in the first person: “I would like to do this work.” It was almost always “…you should do this thing I think is important.”

I roundfiled those letters, but they kept coming.

Which all raises two questions for me:

From Jacquelyn’s fine blog The Contemplative Mammoth, a bit of context:

You’re enjoying your morning tea, browsing through the daily digest of your main society’s list-serv. Let’s say you’re an ecologist, like me, and so that society is the Ecological Society of America*, and the list-serv is Ecolog-l. Let’s also say that, like me, you’re an early career scientist, a recent graduate student, and your eye is caught by a discussion about advice for graduate students. And then you read this:

too many young, especially, female, applicants don’t bring much to the table that others don’t already know or that cannot be readily duplicated or that is mostly generalist-oriented.

I’m not interested in unpacking that statement beyond saying that “don’t bring much to the table that others don’t already know” is basically a really sexist way of saying that they female applicants “are on par with or even slightly exceed others.” There is abundant evidence that perception, not ability, influences gender inequality in the sciences– it’s even been tested empirically.

What I am interested in is why other people in my community don’t think those kinds of comments are harmful and aren’t willing to say something about it if they do.

And then the question:

After the sexist comments were made, some did in fact call them out. This was immediately followed up with various responses that fell into two camps: 1) “Saying female graduate students are inferior isn’t sexist” (this has later morphed into “she was really just pointing out poor mentoring!”), and 2) “Calling someone out for a sexist statement on a list-serv is inappropriate.” Some have called for “tolerance” on Ecolog-l; arguably, more real estate in this discussion has gone into chastising the people who called out Jones’ comments. These people are almost universally male. To those people, I ask:

Why is it more wrong to call someone out for saying something sexist than it was to have said the sexist thing in the first place?

That is a really good question.

[Updated to add:] Apologies to Jacquelyn for misspelling her name at first. Need moar coffee.

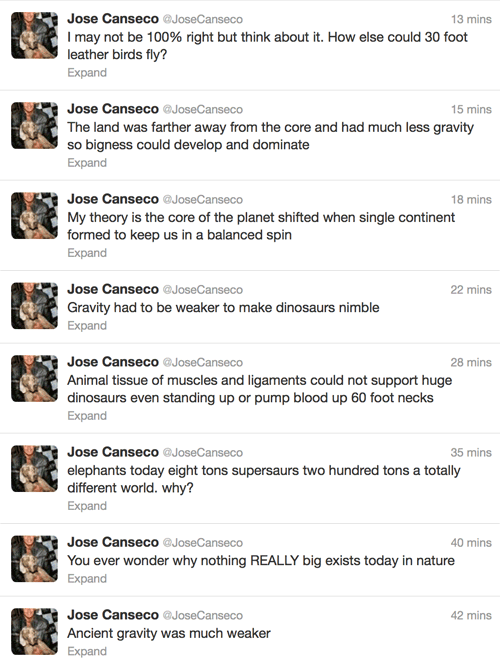

The baseball player Jose Canseco made a remarkable series of tweets yesterday.

I may not be 100% right but think about it. How else could 30 foot leather birds fly?

The land was farther away from the core and had much less gravity so bigness could develop and dominate

My theory is the core of the planet shifted when single continent formed to keep us in a balanced spin

Gravity had to be weaker to make dinosaurs nimble

Animal tissue of muscles and ligaments could not support huge dinosaurs even standing up or pump blood up 60 foot necks

elephants today eight tons supersaurs two hundred tons a totally different world. why?

You ever wonder why nothing REALLY big exists today in nature

Ancient gravity was much weaker

Deja vu, man, deja vu. Any old regulars from the talk.origins usenet group will remember this one: Ted Holden and his endless arguments for Velikovskian catastrophism. Holden also claimed that earth’s gravity had to have been much lower for dinosaurs to stand up.

Ted Holden has been repeatedly posting the claim that sauropod dinosaurs were too large to have existed in 1g acceleration. His argument is based on simple square-cube scaling of human weightlifter performance (in particular, the performance of Bill Kazmaier). His conclusion is that nothing larger than an elephant is possible in 1g. His proposed solution is a “reduction in the felt effect of gravity” (by which he seems to mean the effective acceleration), due to a variant of Velikovskian Catastrophism, often called Saturnism. Ted’s materials in their current form can be found on his web pages dealing with catastrophism.

For those not familiar with Velikovsky, he was a pseudoscientist whose claim to fame was that he so nimbly straddled two disciplines and befuddled people on either side. He was a classical scholar who used his interpretations of ancient texts to claim there was evidence of astronomical catastrophes in Biblical times (his scholarship there impressed astronomers and left the real classical scholars laughing), while also peddling an astronomical model that had planets whizzing out of their orbits and zooming by Earth in near-collisions that caused the disasters in the Bible and other ancient civilizations (his physics dazzled the classical scholars but had physicists gawping in astonishment at their absurdity).

Holden at least tried to do the math; he just flopped and did it wrong. Canseco hasn’t even done that much. Vague and uninformed impressions are not justifications for rejecting science. Here are some quick arguments against this nonsense of dinosaurs living in reduced gravity.

Dinosaurs exhibit the adaptations required for their mass: limbs are thicker in proportion to their length, bones show large muscle insertions, bones are thick and dense, etc. The biology clearly obeys the scaling laws we can see in extant animals.

Holden’s mechanism for reducing gravity is ridiculous: he postulates, for instance, that Mars hovered above the Earth and that its gravitational pull countered part of the Earth’s pull. It would have to be very close to have that effect, and while it’s true that could reduce the ‘felt effect of gravity’, it would only do so briefly before the two planets collided and destroyed all life, and also, you wouldn’t be alive to experience that brief easing of the gravitational load — you’d have been killed in the destructive chaos during the approach, and your body’s behavior would probably be dominated by atmospheric and geological upheavals anyway.

Canseco’s mechanism is pathetic. We already have gravitational variations on the planet, with primary differences between the equator and the poles. These amount to a roughly 0.5% difference in weight — so a 200 pound person weighs 199 pounds at the equator, and 201 pounds at the North Pole. So, most optimistically, if all the gravitational anomalies happened to be piled up on one side of the planet, let’s assume that the Mesozoic variation was greater, all the way up to 1% less on the supercontinent. So that 200 ton supersaur Canseco is concerned about would instead weigh…198 tons. Oooh. That’s enough to make his objections disappear?

At least Canseco is not as delusional as Holden. But if he starts tweeting about giant teratorns carrying Neandertals on their backs, who then fly to Mars and build giant monuments in Cydonia, get him some help, OK?

Hey, go look: Carl Zimmer has a gallery of Cambrian beasties!

My students are also blogging here:

Today was the due date for the take-home exam, which meant everything started a bit late — apparently there was a flurry of last-minute printing and so students straggled in. But we at last had a quorum and I threw worms and maggots at them.

The lab today involves starting some nematode cultures so I gave them a bit of background on that. They’re small, transparent hermaphrodites that can reproduce prolifically and will be squirming about on their plates this week. They’re models for the genetic control of cell lineage and also for inductive interactions: I gave them the specific example of the development of the vulva, in which a subset of cells in close proximity to a cell called the anchor cell develop into the primary fate of forming the walls of the vulva, cells slightly further away follow a secondary fate, forming supporting cells, and cells yet further away form the hypodermis or skin of the worm. I had them make suggestions for how we could test that the anchor cell was the source of an inductive signal, and yay, they were awake enough at 8am to propose some good simple experiments like ablation (should lead to failure of the vulva to form) or translocation (should induce a vulva in a different location). I also brought up genetic experiments to make mutants in the signal gene, in the receptors, and deeper cell transduction pathways.

All those experiments work in the predicted ways, and I was able to show them an epistasis map of the pathways. Two lessons I wanted to get across were that we can genetically dissect these pathways in model organisms, and that when we do so, we often find that toolkit Sean Carrol talks about exposed. For instance, in the signal transduction pathway for the worm vulva, there are some familiar friends in there — ras and raf, kinases that we’ll see again in cancers. And of course there are big differences: mutations in ras/raf in us can lead to cancer rather than eruptions of multiple worm vulvas all over our bodies, because genes downstream differ in their specific roles.

Then we started on a little basic fly embryology: the formation of a syncytial blastoderm, experiments with ligation and pole plasm manipulation in Euscelis that led to the recognition of likely gradients of morphogens that patterned the embryos. From there, we jumped to the studies of Nusslein-Volhard and Wieschaus that plucked out the genes involved in those interactions and allowed whole new levels of genetic manipulation. As the hour was wrapping up, I gave them an overview of the five early classes of patterning genes: the maternal genes that set up the polarity of the embryo; the gap genes that read the maternal gene gradient and are expressed in wide bands; the pair-rule genes that respond to boundaries in gap gene expression and form alternating stripes; the segment polarity genes that have domains of expression within each stripe; and the selector genes that then specify unique properties on spatial collections of segments.

And that’s what we’ll be discussing in more detail over the next few weeks.