The coelacanth genome has been sequenced, which is good news all around…except that I found a few of the comments in the article announcing it disconcerting. They keep calling it a “living fossil” — and you know what I think of that term — and they keep referring to it as evolving slowly

The slowly evolving coelacanth

The morphological resemblance of the modern coelacanth to its fossil ancestors has resulted in it being nicknamed ‘the living fossil’. This invites the question of whether the genome of the coelacanth is as slowly evolving as its outward appearance suggests. Earlier work showed that a few gene families, such as Hox and protocadherins, have comparatively slower protein-coding evolution in coelacanth than in other vertebrate lineages.

Honestly, that’s just weird. How can you say its outward appearance suggests it is slowly evolving? The two modern species are remnants of a diverse group — it looks different than forms found in the fossil record.

And then for a real WTF? moment, there’s this from Nature’s News section.

It is impossible to say for sure, but the slow rate of coelacanth evolution could be due to a lack of natural-selection pressure, Lindblad-Toh says. Modern coelacanths, like their ancestors, “live far down in the ocean, where life is pretty stable”, she says. “We can hypothesize that there has been very little reason to change.” And it is possible that the slow genetic change explains why the fish show such a striking resemblance to their fossilized ancestors.

Snorble-garble-ptang-ptang-CLUNK. Reset. Does not compute. Must recalibrate brain.

None of that makes sense. The modern fish do not show a “striking resemblance” to their fossilize ancestors — they retain skeletal elements that link them to a clade thought to be extinct. This assumption that Actinistian infraclass has been unchanging undermines their conclusions — the modern species are different enough that they’ve been placed in a unique genus not shared with any fossil form.

Then the argument that they must live in a stable environment with a lack of natural-selection pressure is absurd. Selection is generally a conservative process: removing selection pressures from a population should lead to an increase in the accumulation of variability. Do they mean there has been increased selection in a very narrowly delimited but stable environment?

But even that makes no sense. We should still be seeing the accumulation of neutral alleles. Increased selection is only going to remove variability in functional elements, and most of the genome isn’t. I suppose one alternative to explain slow molecular evolution would be extremely high fidelity replication, but even that would require specific selection constraints to evolve.

This article broke my poor brain. I couldn’t see how any of this could work — it ignored the fossil evidence and also seemed to be in defiance of evolutionary theory. It left me so confused.

Fortunately, though, the journal BioEssays came to my rescue with an excellent review of this and past efforts to shoehorn coelacanths into the “living fossil” fantasy, and that also explained the molecular data. And it does it plainly and clearly! It’s titled, “Why coelacanths are not ‘living fossils’”, and you can’t get much plainer and clearer than that.

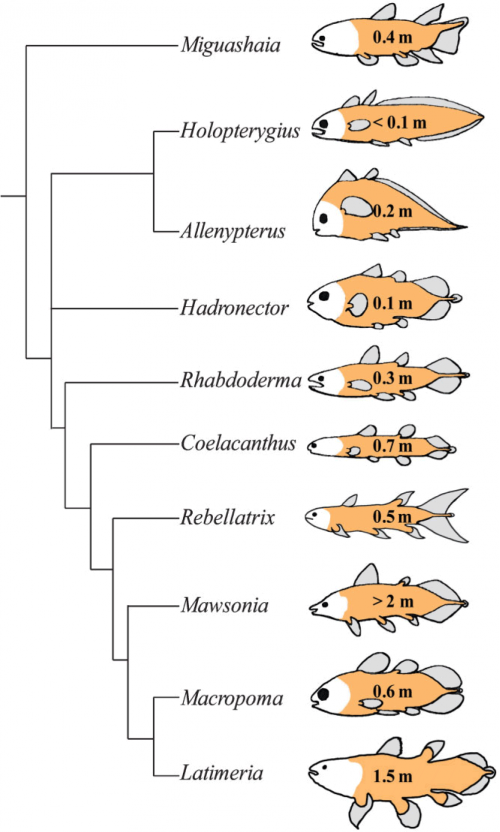

First, let’s dismiss that myth of the unchanging Actinistian. Here’s a phylogeny of the coelacanth-like fossils and their one surviving species.

Comparison of extant and selected extinct actinistians, commonly known as coelacanths. A phylogeny of Actinistia; schematic sketches of body outlines and approximate body length (given in metre) illustrate the morphological diversity of extinct coelacanths: some had a short, round body (Hadronector), some had a long, slender body (Rebellatrix), some were eel-like (Holopterygius) whereas others resembled trout (Rhabdoderma), or even piranha (Allenypterus). Note that the body shape of Latimeria chalumnae differs significantly from that of its closest relative, Macropoma lewesiensis.

Love it. I’ve been looking for a diagram like this for a long time; creationists often trot out this claim that coelacanths haven’t changed in hundreds of millions of years, and there you can see — divergence and variation and evolution, for hundreds of millions of years.

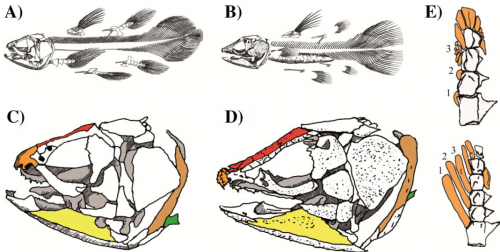

In addition, we can look in more detail at the skull and limbs of these animals. This drawing is comparing modern Latimeria with its closest fossil relative, and even here there are dramatic differences in structure.

Comparison of the skeleton of extant and selected extinct coelacanths. A–D: Latimeria and its sister group Macropoma show numerous skeletal differences. A, B: Overall view of the skeletal organisation of the extant coelacanth and of its closest relative. A: Latimeria chalumnae. B: Macropoma lewesiensis. Relative to the body length, in L. chalumnae the vertebrae are smaller, the truncal region of the vertebral column is longer and the post anal region is shorter than in M. lewesiensis. In the latter region, the hemal arches (ventral spines) extend more ventrally in M. lewesiensis than in L. chalumnae. In addition, the swim bladder is ossified in Macropoma but not in Latimeria, and the basal bone of the first dorsal fin is characteristic of each genus. C, D: Comparison of the skulls of L. chalumnae and M. lewesiensis. C: In L. chalumnae, the mouth opens upward, the articular bone (yellow) is long and narrow, the parietonasal shield (red) is short, the premaxillary bone (orange) is devoid of denticle ornamentation, the dorsal part of the cleithum (light brown) is spiny, and the scapulocoracoid (green) is located on the ventral side. D: In contrast, in M. Lewesiensis, the mouth opens forward, the angular bone (yellow) is triangular, the parieto-nasal shield (red) is long, the premaxillary (orange) protrudes and forms a hemispherical snout which is ornamented with prominent denticles, the dorsal part of the cleithrum (light brown) is thick, and the scapulocoracoid, (green) is located more medially. Modified from [3]. E: Pectoral fin skeleton of L. chalumnae (above) and Shoshonia arctopteryx (below). The three first preaxial radials are numbered from proximal to distal. In L. chalumnae the fin appears nearly symmetrical because radial bones (orange) are arranged nearly symmetrically about the fin axis. The proximal preaxial radials 1-2 are extremely short and bear no fin ray, and the preaxial radial 3 is short and fractionated. In contrast, in S. arctopteryx the fin is strongly asymmetrical chiefly because proximal preaxial radials are long and all bear fin rays.

The authors make it clear that this idea of morphological conservation of the Actinistians is simply bogus.

In addition, an examination of the skeleton of the fossil genus Macropoma (approximately 70 Ma), the sister group of Latimeria and the only known fossil actinistian record from the Cretaceous to the present, shows some interesting differences. Not only are the extant coelacanths three times larger than their closest extinct relatives (about one and a half metres vs. half a metre), but there are also numerous structural differences. The swim bladder is ossified in Macropoma but filled with oil in Latimeria, indicating they were probably found in different types of environments. There are also noticeable differences in the vertebral column (the post anal region is shorter and ventral spines extend less ventrally in M. Lewesiensis compared with L. chalumnae), and in the attachment bones of the fins. In addition, Macropoma and Latimeria have distinctly dissimilar skull anatomies, resulting in noticeable differences in head morphology.

Finally, it should not be forgotten that external morphological resemblances can be based on a very different internal anatomical organisation. The most often emphasised resemblance between coelacanths is that they all have four fleshy-lobed-fins. Until recently, the anatomy of the lobed fins of coelacanths was only known in Latimeria, in which the pectoral fin endoskeleton is short and symmetrical. In 2007, Friedman et al. described the endoskeleton of the pectoral fin of Shoshonia arctopteryx, a coelacanth species from the mid Devonian, and therefore contemporary with Miguashaia. They showed that this earliest known coelacanth fin endoskeleton is highly asymmetrical, a characteristic that is probably ancestral since it resembles the condition found in early sarcopterygians such as Eusthenopteron, Rhizodopsis or Gogonasus. This result is additional support, if needed, that extant coelacanths have not remained morphologically static since the Devonian.

Well, so, you may be wondering, what about the molecular/genomic data? Doesn’t that clearly show that they’ve had a reduced substitution rate? No, it turns out that that isn’t the case. Some genes seem to be more conserved, but others show an expected amount of variation.

However, a closer look at the data challenges this interpretation [of slow evolution]: depending on the analysed sequence, the coelacanth branch is not systematically shorter than the branches leading to other species. In addition, most phylogenetic analyses – including analysis of Hox sequences – do not support the hypothesis that the Latimeria genome is slow evolving, i.e. they do not place coelacanth sequences on short branches nor do they detect low substitution rates. The clearest example, which involves the largest number of genes, is a phylogeny based study of forty-four nuclear genes that does not show a dramatic decrease, if any, in the rate of molecular evolution in the coelacanth lineage. What we know about the biology of coelacanths does not suggest any obvious reason why the coelacanth genome should be evolving particularly slowly.

So why is this claim persisting in the literature? The authors of the BioEssays article made an interesting, and troubling analysis: it depends on the authors’ theoretical priors. They examined 12 relevant papers on coelacanth genes published since 2010, and discovered a correlation: if the paper uncritically assumed the “living fossil” hypothesis (which I’ve told you is bunk), the results in 4 out of 5 cases concluded that the genome was “slowly evolving”; in 7 out of 7 cases in which the work was critical of the “living fossil” hypothesis or did not even acknowledge it, they found that coelacanth genes were evolving at a perfectly ordinary rate.

Research does not occur in a theoretical vacuum. Still, it’s disturbing that somehow authors with an ill-formed hypothetical framework were able to do their research without noting data that contradicted their ideas.

Maybe a start to correcting this particular instance of a problem is to throw out the bad ideas that are leading people astray. The authors strongly urge us to purge this garbage from our thinking.

Latimeria was first labelled as a ‘living fossil’ because the fossil genera were known before the extant species was discovered, and erroneous biological interpretations have grown and reports still show little morphological and molecular evolution. A closer look at the available molecular and morphological data has allowed us to show that most of the available studies do not show low substitution rates in the Latimeria genome, and furthermore, as pointed out by Forey [3] long before us, the supposed morphological stability of coelacanths from the Devonian until the present is not based on real data. As a consequence, the idea that the coelacanth is a biological ‘living fossil’ is a long held but false belief which should not bias the interpretation of molecular data in extant Latimeria populations. The same reasoning could be generalised to other extant species (such as hagfish, lamprey, shark, lungfish and tatuara, to cite few examples of vertebrates) that for various reasons are often presented as ‘ancient’, ‘primitive’, or ‘ancestral’ even if a lot of recent data has shown that they have many derived traits [58–64]. We hope that this review will contribute to dispelling the myth of the coelacanth as a ‘living fossil’ and help biologists keep in mind that actual fossils are dead.

But of course we also shouldn’t let that color our data. If analyses showed a significantly reduced substitution rate in the evolution of a species, it ought to get published. If nothing else, it would be an interesting problem for evolutionary theory. Coelacanths, though, don’t represent that problem.

Amemiya CT, Alföldi J, Lee AP, Fan S, Philippe H, Maccallum I, Braasch I, Manousaki T, Schneider I, Rohner N, Organ C, Chalopin D, Smith JJ, Robinson M, Dorrington RA, Gerdol M, Aken B, Biscotti MA, Barucca M, Baurain D, Berlin AM, Blatch GL, Buonocore F, Burmester T, Campbell MS, Canapa A, Cannon JP, Christoffels A, De Moro G, Edkins AL, Fan L, Fausto AM, Feiner N, Forconi M, Gamieldien J, Gnerre S, Gnirke A, Goldstone JV, Haerty W, Hahn ME, Hesse U, Hoffmann S, Johnson J, Karchner SI, Kuraku S, Lara M, Levin JZ, Litman GW, Mauceli E, Miyake T, Mueller MG, Nelson DR, Nitsche A, Olmo E, Ota T, Pallavicini A, Panji S, Picone B, Ponting CP, Prohaska SJ, Przybylski D, Saha NR, Ravi V, Ribeiro FJ, Sauka-Spengler T, Scapigliati G, Searle SM, Sharpe T, Simakov O, Stadler PF, Stegeman JJ, Sumiyama K, Tabbaa D, Tafer H, Turner-Maier J, van Heusden P, White S, Williams L, Yandell M, Brinkmann H, Volff JN, Tabin CJ, Shubin N, Schartl M, Jaffe DB, Postlethwait JH, Venkatesh B, Di Palma F, Lander ES, Meyer A, Lindblad-Toh K. (2013) The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution. Nature 496(7445):311-316.

Casane D, Laurenti P (2013) Why coelacanths are not ‘living fossils’: A review of molecular and morphological data. Bioessays 35: 332–338.