Yesterday was World Octopus Day — 10/8, don’t you know — but I didn’t celebrate it…because every day is a cephalopod day in my heart. And you don’t get to shackle my heart to beat only one day a year.

Yesterday was World Octopus Day — 10/8, don’t you know — but I didn’t celebrate it…because every day is a cephalopod day in my heart. And you don’t get to shackle my heart to beat only one day a year.

James May, one of the presenters on Top Gear, is trying his hand at providing a little science education. I want to say…please stop. Here he is trying to answer the question, “Are humans still evolving?” In the end he says the right answer — yes they are! — but the path he takes to get there is terrible.

It’s little things that make me wonder if anyone is actually editing his copy. For instance, he helpfully explains that you, the viewer, were produced by your parents having sex. Then he says:

That’s how evolution is driven: by reproduction. But is that still true?

Uh, yes? We haven’t stopped reproducing, so we should be able to stop right there then.

But no, he continues on. He tries to explain evolution, and does manage to verbally describe natural selection correctly as differential survival and reproduction, but it’s illustrated with a pair of goats with telescoping necks. That doesn’t help. He’s describing Darwinian selection and showing it as Lamarckian — it’s a very mixed signal. And as we’ll see, he still seems to be thinking like will and experience drive evolutionary changes.

And do I need to mention that he doesn’t seem aware of processes other than selection in evolution? You need to realize the importance of drift to answer the question of whether evolution is continuing in humans, especially when you’re prone to say glib nonsense like “humans have turned the process of natural selection on its head,” whatever that means.

He also claims along the way that Darwin “tracing this evolutionary process backwards proved that all life came from a common source.” No, he didn’t. A hypothesis is not proof. He found morphological evidence for the relatedness of some groups, but the evidence for common ancestry of all forms wouldn’t really become overwhelming until the molecular evidence linked animals and plants and mushrooms and bacteria together.

By the time he gets around to talking the details of human evolution, we’re mired in a hopeless mess. Apparently, one reason we’re still evolving is that “certain characteristics will improve your chances of breeding” but then he helpfully explains that “its not as if ugly and stupid people don’t get to have children”. So which is it? Is natural selection selecting away for chiseled abs, or whatever he regards as a significant advantage, or isn’t it? And if people he judges as unattractive are having children, that driving force of evolution, then isn’t that undermining his understanding of the process?

And please, if you can’t even get selection straight in your head, please don’t try to explain population structure. He has a weird discursion in which he explains that “the genetic mutations that drive evolution can be most commonly found in a small gene pool” and then somehow tries to argue that we’re “too cosmopolitan,” that the fact that people from all over the world can now intermarry somehow “cuts down on those mutations.” I have no idea what he’s talking about. I suspect he doesn’t either.

Then, as evidence that we have been evolving, he points to big screen TVs as proof that we’re smarter than Stone Age people. Great — we now have a new IQ test. Just measure the dimensions of the individual’s TV. It’ll probably work about as well as regular IQ tests.

He tries to get to specific traits: lack of wisdom teeth is evidence of human evolution, apparently. Never mind that the changes are recent and mixed, and that it’s more likely a plastic response to changes in our diet than a trait that’s been selected for specifically. It’s a very bad example, unless he’s going to argue for selection for people with fewer teeth in their jaws. Do you typically count your date’s molars?

His ultimate proof that humans are evolving is the appearance of lactose tolerance in adults. That is pretty good evidence, I’ll agree…but he messes it up completely.

10,000 years ago, before anybody had had the bright idea of milking a cow, no human could digest the lactose in milk beyond childhood. But now, after a hundred years of drinking cream and milk and squeezy cheese in a can, 99% of people can.

He doesn’t even get the numbers right. North Europeans have a frequency of lactose tolerance of about 90%; in South Europeans it is about 30%, and less than 10% in people of Southeast Asian descent. This is not a largely lactose tolerant world.

And of course, his explanation is screaming nonsense. We are not lactose tolerant because we’ve been drinking milk; we’ve been drinking milk because we’re lactose tolerant. It is not a trait that appeared in the last century.

Why is this guy babbling badly about evolution? Did he have any informed, educated scientists to consult who could tell him not to make such a ghastly botch of it all?

Randy Schekman and Thomas Südhof for their work in vesicle trafficking. We’re working through metabolism in my cell biology course right now, but clearly when we get to translation and export of proteins in a few weeks, I’m going to have to put together a new lecture to cover this subject.

I don’t know why Mary suddenly thinks highlighting a giant man-killing hornet would be appropriate…

…but I’m not going to argue with her.

We’re fostering this wicked little kitty, and one of the things we’re trying to do is get her adopted. To do that, we’re supposed to take a photo, but there’s a problem: she doesn’t hold still. She’s running around everywhere, mauling my squid toys, stuffing her snout in her food bowl, chasing her tail, whatever entertains the tiny brain of a small cat.

So I had to use one of my superpowers. True fact: I have a magical ability to put things to sleep, as my students can attest. But also when my kids were growing up, it almost never failed, put them in my arms and clonk, zzzzz, they were out. So I have tried it on the cat. And it still works. I managed to snap a quick one just as her eyes were closing.

So if you have your own somnolence distortion field, or if you don’t mind an energetic beast, contact the Stevens Community Humane Society, and tell them you want to rescue Ivy from that hellbound Myers household.

John Bohannon of Science magazine has developed a fake science paper generator. He wrote a little, simple program, pushes a button, and gets hundreds of phony papers, each unique with different authors and different molecules and different cancers, in a format that’s painfully familiar to anyone who has read any cancer journals recently.

The goal was to create a credible but mundane scientific paper, one with such grave errors that a competent peer reviewer should easily identify it as flawed and unpublishable. Submitting identical papers to hundreds of journals would be asking for trouble. But the papers had to be similar enough that the outcomes between journals could be comparable. So I created a scientific version of Mad Libs.

The paper took this form: Molecule X from lichen species Y inhibits the growth of cancer cell Z. To substitute for those variables, I created a database of molecules, lichens, and cancer cell lines and wrote a computer program to generate hundreds of unique papers. Other than those differences, the scientific content of each paper is identical.

The fictitious authors are affiliated with fictitious African institutions. I generated the authors, such as Ocorrafoo M. L. Cobange, by randomly permuting African first and last names harvested from online databases, and then randomly adding middle initials. For the affiliations, such as the Wassee Institute of Medicine, I randomly combined Swahili words and African names with generic institutional words and African capital cities. My hope was that using developing world authors and institutions would arouse less suspicion if a curious editor were to find nothing about them on the Internet.

The data is totally fake, and the fakery is easy to spot — all you have to do is read the paper and think a teeny-tiny bit. The only way they’d get through a review process is if there was negligible review and the papers were basically rubber-stamped.

The papers describe a simple test of whether cancer cells grow more slowly in a test tube when treated with increasing concentrations of a molecule. In a second experiment, the cells were also treated with increasing doses of radiation to simulate cancer radiotherapy. The data are the same across papers, and so are the conclusions: The molecule is a powerful inhibitor of cancer cell growth, and it increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to radiotherapy.

There are numerous red flags in the papers, with the most obvious in the first data plot. The graph’s caption claims that it shows a "dose-dependent" effect on cell growth—the paper’s linchpin result—but the data clearly show the opposite. The molecule is tested across a staggering five orders of magnitude of concentrations, all the way down to picomolar levels. And yet, the effect on the cells is modest and identical at every concentration.

One glance at the paper’s Materials & Methods section reveals the obvious explanation for this outlandish result. The molecule was dissolved in a buffer containing an unusually large amount of ethanol. The control group of cells should have been treated with the same buffer, but they were not. Thus, the molecule’s observed “effect” on cell growth is nothing more than the well-known cytotoxic effect of alcohol.

The second experiment is more outrageous. The control cells were not exposed to any radiation at all. So the observed “interactive effect” is nothing more than the standard inhibition of cell growth by radiation. Indeed, it would be impossible to conclude anything from this experiment.

This procedure should all sound familiar: remember Alan Sokal? He carefully hand-crafted a fake paper full of po-mo gobbledy-gook and buzzwords, and got it published in Social Text — a fact that has been used to ridicule post-modernist theory ever since. This is exactly the same thing, enhanced by a little computer work and mass produced. And then Bohannon sent out these subtly different papers to not one, but 304 journals.

And not literary theory journals, either. 304 science journals.

It was accepted by 157 journals, and rejected by 98.

So when do we start sneering at science, as skeptics do at literary theory?

Most of the publishers were Indian — that country is developing a bit of an unfortunate reputation for hosting fly-by-night journals. Some were flaky personal obsessive “journals” that were little more than a few guys with a computer and a website (think Journal of Cosmology, as an example). But some were journals run by well-known science publishers.

Journals published by Elsevier, Wolters Kluwer, and Sage all accepted my bogus paper. Wolters Kluwer Health, the division responsible for the Medknow journals, "is committed to rigorous adherence to the peer-review processes and policies that comply with the latest recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and the World Association of Medical Editors," a Wolters Kluwer representative states in an e-mail. "We have taken immediate action and closed down the Journal of Natural Pharmaceuticals."

Unfortunately, this sting had a major flaw. It was cited as a test of open-access publishing, and it’s true, there are a great many exploitive open-access journals. These are journals where the author pays a fee — sometimes a rather large fee of thousands of dollars — to publish papers that readers can view for free. You can see where the potential problems arise: the journal editors profit by accepting any papers, the more the better, so there’s pressure to reduce quality control. It’s also a situation in which con artists can easily set up a fake journal with an authoritative title, rake in submissions, and then, perfectly legally, publish them. It’s a nice scam. You can also see where Elsevier would love it.

But it’s unfair to blame open access journals for this problem. They even note that one open-access journal was exemplary in its treatment of the paper.

Some open-access journals that have been criticized for poor quality control provided the most rigorous peer review of all. For example, the flagship journal of the Public Library of Science, PLOS ONE, was the only journal that called attention to the paper’s potential ethical problems, such as its lack of documentation about the treatment of animals used to generate cells for the experiment. The journal meticulously checked with the fictional authors that this and other prerequisites of a proper scientific study were met before sending it out for review. PLOS ONE rejected the paper 2 weeks later on the basis of its scientific quality.

The other problem: NO CONTROLS. The fake papers were sent off to 304 open-access journals (or, more properly, pay-to-publish journals), but not to any traditional journals. What a curious omission — that’s such an obvious aspect of the experiment. The results would be a comparison of the proportion of traditional journals that accepted it vs. the proportion of open-access journals that accepted it… but as it stands, I have no idea if the proportion of bad acceptances within the pay-to-publish community is unusual or not. How can you publish something without a control group in a reputable science journal? Who reviewed this thing? Was it reviewed at all?

Oh. It’s a news article, so it gets a pass on that. It’s also published in a prestigious science journal, the same journal that printed this:

This week, 30 research papers, including six in Nature and additional papers published online by Science, sound the death knell for the idea that our DNA is mostly littered with useless bases. A decade-long project, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE), has found that 80% of the human genome serves some purpose, biochemically speaking. Beyond defining proteins, the DNA bases highlighted by ENCODE specify landing spots for proteins that influence gene activity, strands of RNA with myriad roles, or simply places where chemical modifications serve to silence stretches of our chromosomes.

And this:

Life is mostly composed of the elements carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus. Although these six elements make up nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids and thus the bulk of living matter, it is theoretically possible that some other elements in the periodic table could serve the same functions. Here, we describe a bacterium, strain GFAJ-1 of the Halomonadaceae, isolated from Mono Lake, California, that is able to substitute arsenic for phosphorus to sustain its growth. Our data show evidence for arsenate in macromolecules that normally contain phosphate, most notably nucleic acids and proteins. Exchange of one of the major bio-elements may have profound evolutionary and geochemical importance.

I agree that there is a serious problem in science publishing. But the problem isn’t open-access: it’s an overproliferation of science journals, a too-frequent lack of rigor in review, and a science community that generates least-publishable-units by the machine-like application of routine protocols in boring experiments.

The latest celebrity fad is getting pet lorises. They’re adorable! They have such big eyes and a funny face! And look, they like to get tickled!

Aww, so cute. I want one. At least, that seems to be the typical response in followers of pop culture. Anna Nekaris, a professor of primate conservation at Oxford Brookes University, has been documenting the loris fad and doing her best to expose the reality of the loris trade.

They created a Wikipedia page on loris conservation, and Nekaris appeared in a powerful BBC documentary, Jungle Gremlins of Java. The film paints a decidedly less cute picture of loris daily life. In addition to habitat loss, the bushmeat industry, and being used in traditional (read: unscientific) Chinese medicine, the pet trade claims countless lorises each year. Traffickers rip the animals out of their environment—often killing mothers to take their babies—and then isolate the animals in abysmal conditions. Because lorises have formidable canines, dealers pull their fangs or cut them out with nail clippers (and no, they don’t use Novocain on the streets of Java). Many lorises die before they can even be sold as pets.

But back to the case of Sonya, that beloved little tickle monster. Even if she was stolen from a jungle, even if her teeth had been snipped, didn’t she still look like she was enjoying her new home and loving the attention from her owners? Well, I’ll leave you with one last bummer: no, she wasn’t. A loris with its arms up is in a defensive position. The little fireface gets its venomous bite from patches of skin on its inner elbows that secrete an oily toxin. With elbows akimbo, the loris mixes the venom with its saliva and then delivers the powerful concoction with tiny, specially curved teeth on its lower jaw. The bite is extremely painful and takes a long time to heal. And in rare cases, the venom (which some say smells like sweaty socks) can bring on anaphylactic shock and death in humans.

Not so cute anymore, is it? That’s a pissed off loris that wants to bite you and poison you and see you dead.

You may have heard we’ve got this satanic feline padding about the house now, getting into mischief — she has discovered my collection of cephalopodiana, and her favorite toy is one of my stuffed octopuses that she wrestles and bats around the floor. It’s like she’s rubbing it in.

Anyway, a new paper in Nature Communications describes a comparative analysis of the genomes of tigers, lions, snow leopards, and…housecats. I’m not letting her read it, lest she acquire delusions of grandeur (oh, wait, she’s a cat — she already has that.)

There’s nothing too surprising in the data; as usual, we discover that mammals (well, animals, actually) have a solid core of shared genes and the divergence between species is accounted for by changes in a small number of genes. They also exhibit a high degree of synteny — the arrangement of genes on chromosomes are similar.

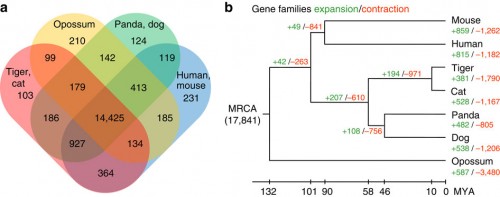

(a) Orthologous gene clusters in mammalian species. The Venn diagram shows the number of unique and shared gene families among seven mammalian genomes. (b) Gene expansion or contraction in the tiger genome. Numbers designate the number of gene families that have expanded (green, +) and contracted (red, −) after the split from the common ancestor. The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) has 17,841 gene families. The time lines indicate divergence times among the species.

But note the cladogram on the right, and this bit of information we must keep from the cats.

The tiger genome sequence shows 95.6% similarity to the domestic cat from which it diverged approximately 10.8 million years ago (MYA); human and gorilla have 94.8% similarity and diverged around 8.8 MYA.

The difference between a housecat and a tiger is a mere ten million years. If only they knew…

I plan to allow this cat to continue to play with my cephalopods. Distraction, you know.

Cho YS, Hu L, Hou H, Lee H, Xu J, Kwon S, Oh S, Kim H-M, Jho S, Kim S, Shin Y-A,Kim BC, Kim H, Kim C-u, Luo SJ, Johnson WE,Koepfli K-P, Schmidt-Küntzel A, Turner JA, Marker L et al. (2013) The tiger genome and comparative analysis with lion and snow leopard genomes. Nature Communications 4, Article number: 2433 doi:10.1038/ncomms3433