Acanthaspis petax, a type of assassin bug, stacks dead ant bodies on its back to confuse predators. Photo by Mohd Rizal Ismail

Acanthaspis petax, a type of assassin bug, stacks dead ant bodies on its back to confuse predators. Photo by Mohd Rizal Ismail

Check it out: true stories of evolutionary theory.

Look it over, the Avail Programming Language was released to the public just today.

(What a random thing for me to mention, you might be thinking…until you look at the credits.)

You know, fear of holes…it doesn’t bother me at all, but about 20 seconds into this video, you’ll see a pocked surface suddenly erupt into mouths on wormlike stalks, and I wouldn’t want to be responsible for any trypophobia induced heart attacks. Oh, and everything after 1:50 — you might die.

(via Mother Nature Network)

Every time I go to Washington DC I try to find time to visit the fossil hall, which is damn good (not quite as good as the AMNH’s, though, which gets my highest marks for an informative dino experience). But now the bad news: it’s being closed for five long years. The good news, though, is it will reopen with a complete renovation and a new and very complete T. rex skeleton.

Now I guess I have to stay alive for five more years to see if DC can have a better exhibit than New York. One more reason to not die…

We’ve had a creationist named “biasevolution” babbling away in the comments. He’s not very bright and he’s longwinded, always a disastrous combination, and he tends to echo tedious creationist tropes that have been demolished many times before. But hey, I’m indefatigable, I can hammer at these things all day long.

He brings up irreducible complexity (IC), Behe’s ever-popular contribution to the creationism debate. Behe’s version of the idea was published in 1996, so we’ve had almost 20 years to refute it — successfully! — so it gets a little old seeing it brought up again and again.

If you really, really understood IC you WOULD NOT argue with it. You would find that it would be as silly as say arguing against variation or heredity, or the principle of flotation. The reason is this: if you must design a system towards some given function or set of function you would need critical parts. For one, you must have a source of energy for that system. Two, it must have a set of interacting parts that work towards the function you want, you can even add parts to fine-tune it to better perform that function (eg adding capacitors to fans to smoothen out voltage reduced). To then argue that an eye ain’t IC is laughable. All the accounts supposedly falsifying IC or showing how it evolved routinely assume simple IC precursors or point to other IC systems lacking a part and say IC is refuted for a system as Miller did in the blood clotting cascade (akin to arguing because some cars don’t use clutches cars ain’t IC).

I do understand IC quite well. I’ve read Behe’s books. I’ve had it thrown in my face many times, often by creationists who don’t understand it (Jerry Bergman’s claim that carbon all by itself is irreducibly complex was particularly memorable). Biasevolution’s version isn’t quite that bad, but it’s still awful.

And it’s wrong.

First, there’s the problem of begging the question: if you must design a system towards some given function

. You’re trying to argue that something is designed, and the first thing you do is demand that we accept the premise that it is designed?

The whole point of the IC concept is that if you examine a final ‘design’, and there’s no way to remove a piece of the structure without destroying its function, then it could not have evolved in a stepwise fashion, as evolution would predict. That’s really all it says: that evolution is falsified if you identify a pathway, for instance, that would not be functional if you removed a piece. It’s naively appealing — but only if you think evolutionary change must be symmetrical and reversible. But we actually evolve irreducibly complex systems all the time.

Let’s work through a simple example. Here’s a pathway, or circuit: a battery, a switch, and a light bulb (I’ve left out the one wire to complete the circuit, just to simplify it all; don’t take it too literally.) You close the switch, the bulb lights up. Simple.

Here’s a simple expansion of that circuit. I’ve merely duplicated the switch, so now there’s two of them: close either one, the bulb lights up. This might not be a trivial change to an electrician, but it is to a geneticist — genes get duplicated all the time, and typically all it would do is add a redundant element. So this is a routine variation of a kind that is frequently observed in biological systems.

Now we change one wire, shifting the output of the first switch from directly activating the effector (the bulb) to feeding into the second switch. Now to light up the bulb, you must close the second switch, but the first switch is redundant.

The biological analog to this would be if, for instance, a protein in a biochemical pathway lost its ability to bind a terminal substrate, but could still activate an intermediate protein. Again, this happens.

Now you could imagine a mutation that destroyed the first switch, and the whole system would simply revert to the initial condition, in which a single switch controls the bulb. That happens, too — we find dead genes (called pseudogenes) all over the genome.

Or, just as possible, what if you kept the first switch but lost another wire?

This is an interesting change. Now, to light up the bulb, you have to close both the first and second switch. It also fits Behe’s description of an irreducibly complex system, because removing any part, the battery, the first switch, or the second switch, produces a pathway that cannot light up the bulb. It’s a dead system. It is most definitely irreducibly complex by any reading of Behe’s hypothesis.

But does that mean it could not have evolved by the incremental addition or subtraction of parts, with every step retaining the full capability of lighting up the bulb? Of course not. I just led you through each step, and in all four of the cartoons above, you can turn the lightbulb on. The fact of ICness does not vitiate the idea of incremental evolution.

So naive creationists will look at the fact of the organization of the eye, that you cannot remove the optic nerve or the retina and still have a functional eye, and fallaciously argue that that means it could not have evolved. This is logically false. I can point to lots of biological systems that can be called irreducibly complex: I am personally irreducibly complex, for instance, because I would stop functioning if you cut out my heart or gave me a brainectomy or deleted a big chunk of my immune system — but that fact is not sufficient to demonstrate that evolution couldn’t have done it.

I’ve been pointing this out to creationists for well over a decade, and all I ever get from them is stupefied stares and the occasional splutter. I don’t expect it will sink in this time, either. But I do derive a certain rude satisfaction from the fact that creationists repeatedly exhibit that same dumb incomprehension every time, so I’ll keep puncturing them with it.

Recently, Carl Zimmer made a criticism of the computer animations of molecular events (it’s the same criticism I made 8 years ago): they’re beautiful and they’re informative, but they leave out the critical aspect of stochastic behavior that is important in understanding the biochemistry. He’s talking specifically about kinesin, a transport protein which the animators are particularly fond of illustrating.

Every now and then, a tiny molecule loaded with fuel binds to one of the kinesin “feet.” It delivers a jolt of energy, causing that foot to leap off the molecular cable and flail wildly, pulling hard on the foot that’s still anchored. Eventually, the gyrating foot stumbles into contact again with the cable, locking on once more — and advancing the vesicle a tiny step forward. This updated movie offers a better way to picture our most intricate inner workings…. In the 2006 version, we can’t help seeing intention in the smooth movements of the molecules; it’s as if they’re trying to get from one place to another. In reality, however, the parts of our cells don’t operate with the precise movements of the springs and gears of a clock. They flail blindly in the crowd.

The illusion of directed, purposeful movement is a simplifying shortcut: as Zimmer describes, there actually is a lot of noise in the system, it’s just that the thermodynamics of the interactions promote a directionality to the motion. This is Chemistry 101. I figured that everyone with an undergraduate level of understanding of molecules would be able to grasp this.

I did not take into account willful ignorance, however. Jonathan Wells is angry that anyone dared to question the perfect “stately grace” of molecular machines, and accuses proponents of stochastic motion of Flailing Blindly: The Pseudoscience of Josh Rosenau and Carl Zimmer. He has a Ph.D. in biology, and he doesn’t understand what I just said was Chem 101? For shame.

But that’s not what the biological evidence shows. In fact, kinesin moves quickly, with precise movements, to get from one place to another. A kinesin molecule takes one 8-nanometer “step” along a microtubule for every high-energy ATP molecule it uses, and it uses about 80 ATPs per second. On the scale of a living cell, this movement is very fast. To visualize it on a macroscopic scale, imagine a microtubule as a one-lane road and the kinesin molecule as an automobile. The kinesin would be traveling over 200 miles per hour!

The speed of the reaction doesn’t say anything about the specifics of the molecular movement…and it’s especially not convincing when your trick is to multiply the actual speed in the cell by approximately 1012 to scale it up to the size of a car. The flow rate of the Mississippi river is about 1.5 miles per hour here in Minnesota — if you multiply that by 1012, oh my god, the water is moving at about 2000 times the speed of light!

But let’s set aside the stupid inflation for a minute. Wells cites a couple of papers to back up his claim of the rate of ATP consumption. It’s true. But it doesn’t show that the movement is steady and machine-like and precise at all. He must be trusting us to not bother even reading the paper.

Here’s the deal: we can actually watch single molecules of kinesin behaving. The typical trick is to use a fluorescent bead, attach that to kinesin, and then record the glowing bead’s movement as it is moving along with optical-trapping interferometry. That’s the problem with Wells’ accusation: we actually see the behavior, and it’s not linear, smooth, and graceful.

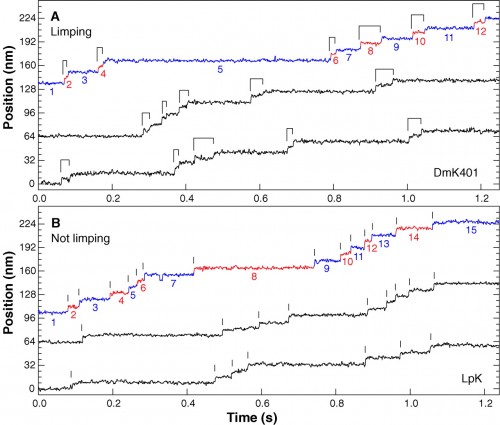

This is the data that the paper used to measure the quantum, jerky behavior of kinesin. Just look at the top graph: that’s a record of the bead’s movement over time. You should be able to see that the line holds steady at one distance for variable lengths of time, and then jerks upward. The “jerks” are distances of about 8nm, and the other graphs are power spectra to show that there is a peak periodicity of 8nm. It shows the opposite of what Wells claims; there are long pauses and sudden shifts in the directly observed track of kinesin movement. The 8nm emerges because when one “foot” of kinesin releases and wobbles forward to connect to tubulin, it has an 8nm step.

Horizontal grid lines (dotted lines) are spaced 8 nm apart. Data were median-filtered with a window width of 60 ms. b, Normalized histogram of pairwise distances between all pairs of data points in this record, showing a clear 8-nm periodicity. c, Normalized power spectrum of the data in b, displaying a single prominent peak at the reciprocal of 8 nm (arrow). d, Variance in position, averaged over 28 runs at 2 microM ATP (dots), and line fit over the interval 3.5 ms to 1.1 s. The y-intercept of the fit is determined by equipartition, left fencex2right fence = kT/alpha, where alpha is the combined stiffness of the optical trap and bead–microtubule linkage. The rapid rise in variance at short times reflects the brownian correlation time for bead position.

You can find lots of papers with direct observations of kinesin movement. Here’s data from another paper that essentially shows that the two ‘feet’ of kinesin alternate in their movement, because they made recombinant, asymmetric kinesin with slightly different step distances. Again, note the long dwell times punctuated with surges of movement.

Representative high-resolution stepping records of position against time, showing the single-molecule behavior of kinesin motors under constant 4 pN rearward loads. (A) Limping motion of the recombinant kinesin construct, DmK401. The dwell intervals between successive 8-nm steps alternate between slow and fast phases, causing steps to appear in pairs, as indicated by the ligatures. (B) Nonlimping motion of native squid kinesin, LpK. No alternation of steps is apparent; vertical lines mark the stepping transitions. Slow and fast phase assignments, as described in the text, are indicated in color on the uppermost trace of each panel (blue and red, respectively), and the corresponding dwell intervals are numbered. All traces were median filtered with a 2.5-ms window.

The contrast is between “stately grace” and “jiggle and jump”. The evidence shows that it is the latter. Yet, somehow, Wells closes his weird series of non sequiturs with this question, as if he expects everyone to give him the answer he wants.

So, who are the pseudoscientists?

The answer is obvious. Wells and his cronies at the DI.

Asbury CL, Fehr AN, Block SM (2003) Kinesin moves by an asymmetric hand-over-hand mechanism. Science 302(5653):2130-4

Schnitzer MJ, Block SM (1997) Kinesin hydrolyses one ATP per 8-nm step. Nature388(6640):386-90.

By the way, I found about this because the Discovery Institute sent me email (silly season and all) proudly announcing that they were about to release evidence that would clearly rebut Zimmer’s assertion that kinesin “flails blindly” — they are making a computer animation showing that it doesn’t.

Yes, they are that stupid.

Do not search for information on getting sand in your genitals. It’s a morass of nonsense out there, with all kinds of bizarre pop culture notions. Most of it seems to be about getting sand in your vagina, which is treated as slogan to mock and trivialize women’s problems, but getting sand under your foreskin…oh, my. That’s no joke. That’s a very serious problem that must be dealt with surgically.

Remember Brian Morris, the Australian circumcision fanatic? One of his talking points is that getting sand in your penis is a major problem for uncircumcised men, and that in particular entire armies have been devastated in the desert by grains of sand getting caught up there, or laid flat in the jungles by all the damp rot and unhygienic conditions. He paints a grisly picture of the uncircumcised penis, and claims that it’s standard military policy to make sure you don’t have one of those dangerous folds of skin. How can you possibly fight if you’ve got a tiny, hideous bit of flesh attached to your penis?

I really had no idea. I may be a flabby old college professor, but apparently because I was born in America in the 1950s, when every boy baby was given cosmetic surgery practically as soon as they were born, I can whip the ass of every anteater boy out there. Good to know.

Morris is rather insistent. He claims that circumcision is a serious medical issue for the military.

In attempting to ridicule the notion that circumcision arose in the Middle East to solve problems caused by ‘sand and dust’, Vernon cites an article by Robert Darby, an anti-circ activist. Darby’s claims stemming from ‘medical records’ ‘he analyzed’ are false. Infections, initiated by the aggravation of dirt and sand, are not uncommon under desert conditions, and have even crippled whole armies of uncircumcised soldiers. It is difficult to achieve sanitation during prolonged battle. To contradict Darby, and thus Vernon, a US Army report by General Patton stated that in World War II 150,000 soldiers were hospitalised for foreskin problems due to inadequate hygiene. To quote: “Time and money could have been saved had prophylactic circumcision been performed before the men were shipped overseas” and “Because keeping the foreskin clean was very difficult in the field, many soldiers with only a minimal tendency toward phimosis were likely to develop balanoposthitis”. The story was similar in Iraq during ‘Desert Storm’ in the early 1990s. In the Vietnam War men requested circumcision to avoid “jungle rot”.

Well, if General George Patton thought it was a serious problem, it must be so. “Old Blood and Guts” wouldn’t be put off by trivia.

Except, well, it turns out that Brian Morris is rather sloppy with the facts.

Attempting to refute my argument he cites “a US Army report by General Patton”, and lists a series of pages that are supposed to back up his claim. But when you actually check those pages you find that they have nothing to do with sand under the foreskin and fail to provide any support for the argument that Morris wishes to make. For a start he gets the details of the book wrong. It is not a “report by General Patton”, but a multi-author volume in the official history of U.S. medical services in World War 2, edited by John F. Patton MD. Secondly, there are only two occurrences of the word sand in the entire volume, neither of which has anything to do with foreskins or circumcision. The volume scarcely deals with the Middle Eastern or North African (desert) combat theatres, but mostly with the South-East Asian and Pacific theatres, characterized by dense jungles and wet, humid conditions that posed many intractable health problems, affecting many parts of the body, not just the penis. But in those conditions sand and dust were not an issue. There is not the slightest support for his hyperbolic claim that “Infections, initiated by the aggravation of dirt and sand, are not uncommon under desert conditions, and have even crippled whole armies of uncircumcised soldiers.”

I’m sure you uncircumcised men are quite pleased to hear this. You don’t need to get the tip lopped off in order to go kill people in the Middle East. And I’ve lost my last possible advantage in a bar fight.