I spend my weekends preparing the lectures for my coming week, and today the Far Side featured the perfect image for my title slide.

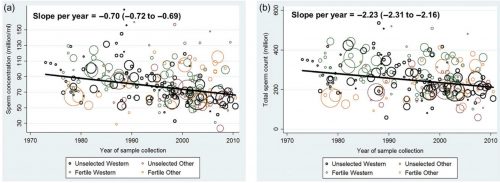

The subject? Aging and cancer as developmental diseases.

It is kind of awkward being a 67-year-old geezer talking to 19-21 year olds about aging. If this were a laboratory course I could just flop down on a table and let them dissect me.