There’s another paper out debunking the ENCODE consortium’s absurd interpretation of their data. ENCODE, you may recall, published a rather controversial paper in which they claimed to have found that 80% of the human genome was ‘functional’ — for an extraordinarily loose definition of function — and further revealed that several of the project leaders were working with the peculiar assumption that 100% must be functional. It was a godawful mess, and compromised the value of a huge investment in big science.

Now W. Ford Doolittle has joined the ranks of many scientists who immediately leapt into the argument. He has published “Is junk DNA bunk? A critique of ENCODE” in PNAS.

Do data from the Encyclopedia Of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project render the notion of junk DNA obsolete? Here, I review older arguments for junk grounded in the C-value paradox and propose a thought experiment to challenge ENCODE’s ontology. Specifically, what would we expect for the number of functional elements (as ENCODE defines them) in genomes much larger than our own genome? If the number were to stay more or less constant, it would seem sensible to consider the rest of the DNA of larger genomes to be junk or, at least, assign it a different sort of role (structural rather than informational). If, however, the number of functional elements were to rise significantly with C-value then, (i) organisms with genomes larger than our genome are more complex phenotypically than we are, (ii) ENCODE’s definition of functional element identifies many sites that would not be considered functional or phenotype-determining by standard uses in biology, or (iii) the same phenotypic functions are often determined in a more diffuse fashion in larger-genomed organisms. Good cases can be made for propositions ii and iii. A larger theoretical framework, embracing informational and structural roles for DNA, neutral as well as adaptive causes of complexity, and selection as a multilevel phenomenon, is needed.

In the paper, he makes an argument similar to one T. Ryan Gregory has made many times before. There are organisms that have much larger genomes than humans; lungfish, for example, have 130 billion base pairs, compared to the 3 billion humans have. If the ENCODE consortium had studied lungfish instead, would they still be arguing that the organism had function for 104 billion bases (80% of 130 billion)? Or would they be suggesting that yes, lungfish were full of junk DNA?

If they claim that lungfish that lungfish have 44 times as much functional sequence as we do, well, what is it doing? Does that imply that lungfish are far more phenotypically complex than we are? And if they grant that junk DNA exists in great abundance in some species, just not in ours, does that imply that we’re somehow sitting in the perfect sweet spot of genetic optimality? If that’s the case, what about species like fugu, that have genomes one eighth the size of ours?

It’s really a devastating argument, but then, all of the arguments against ENCODE’s interpretations have been solid and knock the whole thing out of the park. It’s been solidly demonstrated that the conclusions of the ENCODE program were shit.

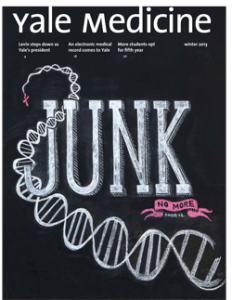

So why, Yale, why? The Winter edition of the Yale Medicine magazine features as a cover article Junk No More, an awful piece of PR fluff that announces in the first line “R.I.P., junk DNA” and goes on to tout the same nonsense that every paper published since the ENCODE announcement has refuted.

The consortium found biological activity in 80 percent of the genome and identified about 4 million sites that play a role in regulating genes. Some noncoding sections, as had long been known, regulate genes. Some noncoding regions bind regulatory proteins, while others code for strands of RNA that regulate gene expression. Yale scientists, who played a key role in this project, also found “fossils,” genes that date to our nonhuman ancestors and may still have a function. Mark B. Gerstein, Ph.D., the Albert L. Williams Professor of Biomedical Informatics and professor of molecular biophysics and biochemistry, and computer science, led a team that unraveled the network of connections between coding and noncoding sections of the genome.

Arguably the project’s greatest achievement is the repository of new information that will give scientists a stronger grasp of human biology and disease, and pave the way for novel medical treatments. Once verified for accuracy, the data sets generated by the project are posted on the Internet, available to anyone. Even before the project’s September announcement, more than 150 scientists not connected to ENCODE had used its data in their research.

“We’ve come a long way,” said Ewan Birney, Ph.D., of the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) in the United Kingdom, lead analysis coordinator for ENCODE. “By carefully piecing together a simply staggering variety of data, we’ve shown that the human genome is simply alive with switches, turning our genes on and off and controlling when and where proteins are produced. ENCODE has taken our knowledge of the genome to the next level, and all of that knowledge is being shared openly.”

Oh, Christ. Not only is it claiming that the 80% figure is for biological activity (it isn’t), but it trots out the usual university press relations crap about how the study is all about medicine. It wasn’t and isn’t. It’s just that dumbasses can only think of one way to explain biological research to the public, and that is to suggest that it will cure cancer.

As for Birney’s remarks, they are offensively ignorant. No, the ENCODE research did not show that the human genome is actively regulated. We’ve known that for fifty years.

That’s not the only ahistorical part of the article. They also claim that the idea of junk DNA has been discredited for years.

Some early press coverage credited ENCODE with discovering that so-called junk DNA has a function, but that was old news. The term had been floating around since the 1990s and suggested that the bulk of noncoding DNA serves no purpose; however, articles in scholarly journals had reported for decades that DNA in these “junk” regions does play a regulatory role. In a 2007 issue of Genome Research, Gerstein had suggested that the ENCODE project might prompt a new definition of what a gene is, based on “the discrepancy between our previous protein-centric view of the gene and one that is revealed by the extensive transcriptional activity of the genome.” Researchers had known for some time that the noncoding regions are alive with activity. ENCODE demonstrated just how much action there is and defined what is happening in 80 percent of the genome. That is not to say that 80 percent was found to have a regulatory function, only that some biochemical activity is going on. The space between genes was also found to contain sites where DNA transcription into RNA begins and areas that encode RNA transcripts that might have regulatory roles even though they are not translated into proteins.

I swear, I’m reading this article and finding it indistinguishable from the kind of bad science I’d see from ICR or Answers in Genesis.

I have to mention one other revelation from the article. There has been a tendency to throw a lot of the blame for the inane 80% number on Ewan Birney alone…he threw in that interpretation in the lead paper, but it wasn’t endorsed by every participant in the project. But look at this:

The day in September that the news embargo on the ENCODE project’s findings was lifted, Gerstein saw an article about the project in The New York Times on his smartphone. There was a problem. A graphic hadn’t been reproduced accurately. “I was just so panicked,” he recalled. “I was literally walking around Sterling Hall of Medicine between meetings talking with The Times on the phone.” He finally reached a graphics editor who fixed it.

So Gerstein was so concerned about accuracy that he panicked over an article in the popular press, but had no problem with the big claim in the Birney paper, the one that would utterly undermine confidence in the whole body of work, did not perturb him? And now months later, he’s collaborating with the Yale PR department on a puff piece that blithely sails past all the objections people have raised? Remarkable.

This is what boggles my mind, and why I hope some sociologist of science is studying this whole process right now. It’s a revealing peek at the politics and culture of science. We have a body of very well funded, high ranking scientists working at prestigious institutions who are actively and obviously fitting the data to a set of unworkable theoretical presuppositions, and completely ignoring the rebuttals that are appearing at a rapid clip. The idea that the entirety of the genome is both functional and adaptive is untenable and unsupportable; we instead have hundreds of scientists who have been bamboozled into treating noise as evidence of function. It’s looking like N rays or polywater on a large and extremely richly budgeted level. And it’s going on right now.

If we can’t have a sociologist making an academic study of it all, can we at least have a science journalist writing a book about it? This stuff is fascinating.

I have my own explanation for what is going on. What I think we’re seeing is an emerging clash between scientists and technicians. I’ve seen a lot of biomedical grad students going through training in pushing buttons and running gels and sucking numerical data out of machines, and we’ve got the tools to generate so much data right now that we need people who can manage that. But it’s not science. It’s technology. There’s a difference.

A scientist has to be able to think about the data they’re generating, put it into a larger context, and ask the kinds of questions that probe deeper than a superficial analysis can deliver. A scientist has to be more broadly trained than the person who runs the gadgetry.

This might get me burned at the stake worse than sneering at ENCODE, but a good scientist has to be…a philosopher. They may not have formal training in philosophy, but the good ones have to be at least roughly intuitive natural philosophers (ooh, I’ve heard that phrase somewhere before). If I were designing a biology curriculum today, I’d want to make at least some basic introduction to the philosophy of science an essential and early part of the training.

I know, I’m going against the grain — there have been a lot of big name scientists who openly dismiss philosophy. Richard Feynman, for instance, said “Philosophy of science is about as useful to scientists as ornithology is to birds.” But Feynman was wrong, and ironically so. Reading Feynman is actually like reading philosophy — a strange kind of philosophy that squirms and wiggles trying to avoid the hated label, but it’s still philosophy.

I think the conflict arises because, like everything, 90% of philosophy is garbage, and scientists don’t want to be associated with a lot of the masturbatory nonsense some philosophers pump out. But let’s not lose sight of the fact that some science, like ENCODE, is nonsense, too — and the quantity of garbage is only going to rise if we don’t pay attention to understanding as much as we do accumulating data. We need the input of philosophy.