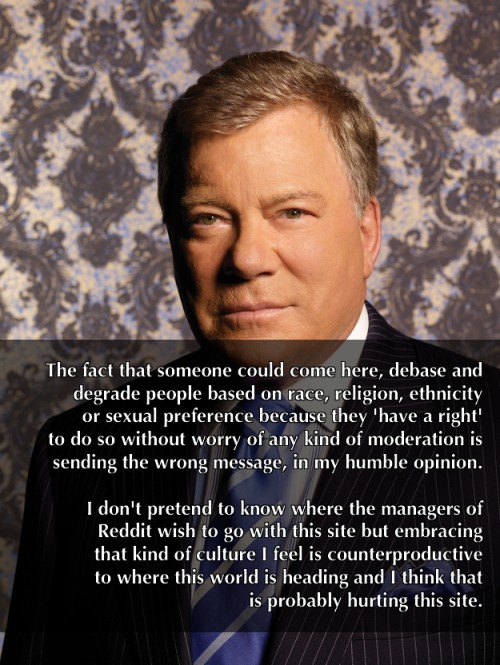

Captain Kirk always was willing to violate the Prime Directive when it suited him. He went on Reddit to do an IAmA, and guess what he did? Shatner dissed Reddit and the whole idea of irresponsible speech!

Now watch: I’m going to immediately derail the whole comment thread by starting a real nerd war: This just confirms that Star Trek TOS was the very best of all the Star Treks.