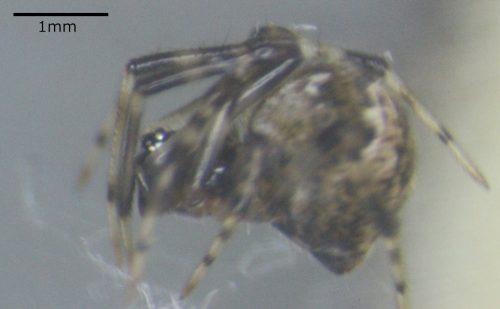

Steatoda triangulosa, hovering watchfully over her egg sac.

We also set up 8 Parasteatoda tepidariorum with mates today. For the most part, all went well, with the males approaching tentatively and plucking at the female’s web, as they should. One female went berserk when we added a male, chasing him all over the cage while he frantically scurried away. We were concerned that we ought to split them up, but they’d reached a cautious détente after about 20 minutes, so maybe their relationship will work out.

We’ll know in a week or two if we see more egg sacs.