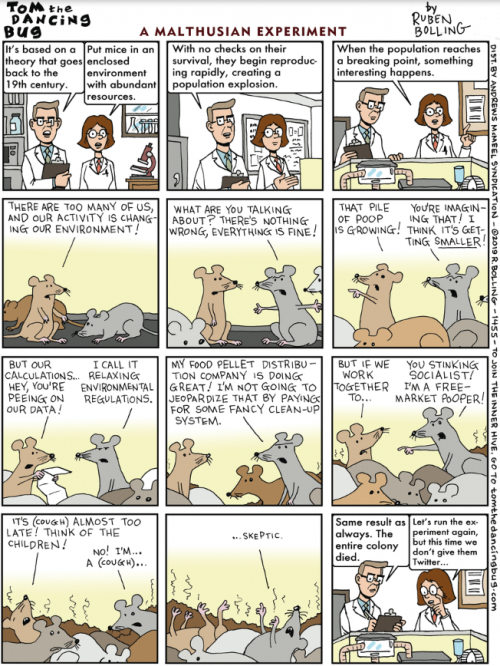

Why aren’t you?

It’s 53 seconds. Please watch and listen to all of this. It captures the absolute emergency we are facing, and how we have to stop dithering today. We all are in dire peril, but it’s not too late if we act quickly. pic.twitter.com/qsHP7cutKi

— Terry McGlynn (@hormiga) September 23, 2019

She seems to be the only one making an honest response to our situation.