I think I saw this tree in a Dr Seuss book once upon a time. Unfortunately, all the source says about is that it is “typical habitat of the Western Clawless Upside-down Fly, Nothoastia clausa.” That belongs in Dr Seuss, too.

(Also on Sb)

I think I saw this tree in a Dr Seuss book once upon a time. Unfortunately, all the source says about is that it is “typical habitat of the Western Clawless Upside-down Fly, Nothoastia clausa.” That belongs in Dr Seuss, too.

(Also on Sb)

Salon has also picked up my Near death, rehashed article, which further abuses Mario Beauregard. Let’s see what New Agers come scuttling out of the woodwork again.

The latest Carnival of Evolution is at Evolving Thoughts, hosted by that guy Wilkins who usually covers the philosophical beat…but we’ll let him out of that cage this one time.

The Carnival of Evolution 48 will be held right here, on Pharyngula. You can submit entries via the carnival widget; get them in before 1 June, or I’ll ignore them and they’ll be passed on to the next carnival host, who doesn’t exist. And therefore doesn’t have a blog. Which means your carefully crafted science post will be shipped off to dev:null. So you might also consider volunteering for the hosting duties some time. The electrons you save might be your own.

(Also on Sb)

Cholera is an ugly little beast loaded with all kinds of nasty optimizations to kill human beings. Read this post for a nice summary of all the gory details, and then after explaining all the specific elements of the cholera toxin, asks this plangent question:

How would a Creationist or I.D. advocate explain all of this? They don’t believe that bacteria can develop significant new adaptations, so they’d have to attribute all these changes to recent surreptitious tinkering by an Intelligent Designer (who is presumably still tinkering with cholera bacteria to make it look like they’re evolving, of course). For the sake of argument, let’s assume for a minute that this unlikely explanation is true. If so, we could deduce at least three things about the Intelligent Designer (possibly more):

1) The Intelligent Designer does not like humans. (Why else would s/he/it design lethal pathogens?)

2) The Intelligent Designer is tricking us by surreptitiously intervening in a way that makes it look like bacteria are evolving in order to fool us.

3) The Intelligent Designer is not very smart. If you were an all-powerful Intelligent Designer that wanted to make bacteria that would kill lots of humans, you could do a much better job, because cholera bacteria don’t survive very well in highly acidic conditions. The vast majority of the cholera bacteria you ingest when you drink contaminated water will perish in your stomach acid. From an evolutionary perspective this makes perfect sense, because we know that cholera became a killer through a blind process of evolution by natural selection. From a Creationist or I.D. perspective, however, it makes no sense at all. Indeed, the only way a Creationist or I.D. advocate can explain cholera is to shrug and say that “God moves in mysterious ways”, which is just dodging the question altogether.

Some recognize the problem. I’ll recommend (!) Michael Behe’s book, The Edge of Evolution, which isn’t very good science but at least he comes right up to this problem of the parasites and nasty-man killing nature of Nature, and comes right out and says it: his Intelligent Designer had to have gone in to specifically engineer every brutal feature of every hostile microbe and protist. Further, his Designer is pursuing an ongoing project, and is intentionally introducing almost every significant set of mutations to make pathogens more lethal right now.

I’ve been amused to see the stunned and embarrassed silence of the creationist community to that book. They laud Behe still for Darwin’s Black Box, but The Edge of Evolution? Nah, let’s pretend that one didn’t happen.

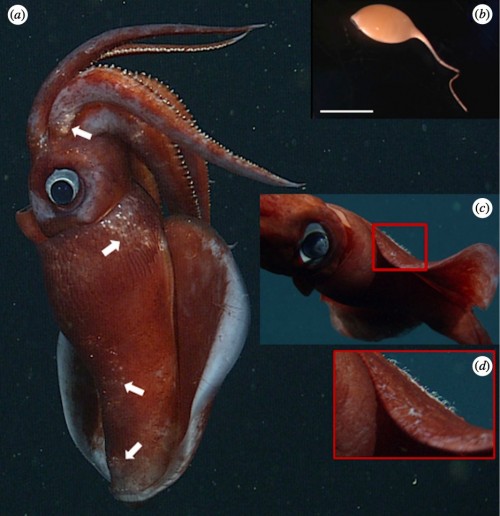

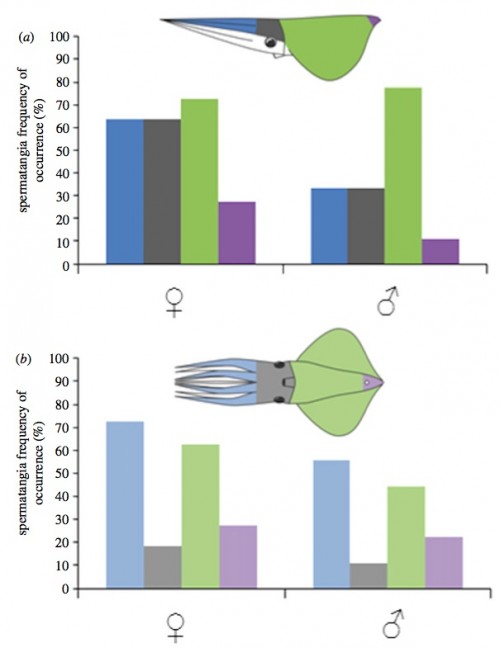

Some species of cephalopods are incapable of concealing their sexual history. The males produce packets of sperm called spermatangia that they grasp with a specialized arm that they then reach out and splat, poke into their mate. In Octopoteuthis deletron, a deep-sea squid, these spermatangia are large, pale, and distinctive, so every time a squid is mated it’s left with a little white dangling flag marking it — so sex is like a combination of tag and paintball. The males are loaded with ammo — 1646 were counted in the reproductive tract of one male — and the spermatangia can be counted using a video camera.

So a ROV went down deep into the Monterey Submarine Canyon and documented the profligate promiscuity of these squid. The females had been busy: individuals had between 21 and 147 spermatangia dangling from them.

The surprise was that the males were equally likely to have been inseminated multiple times in their life, between 15 and 25 times. They’re all manic bisexuals! They’re also creative in their sexual behavior; as you can see below, spermatangia are implanted everywhere, mantle, arms, ventrally, dorsally. It’s all one big gay orgy down there under the sea.

Most cephalopods, this species included, live short lives and the perpetuation of the species relies on rapid, successful mating. The authors explain this same-sex mating behavior as an adaptive response to a life-style in which discrimination is less important than simply getting the job done.

We have only observed them as solitary individuals. The combination of a solitary life, poor sex differentiation, the difficulty of locating a conspecific and the rapidity of the sexual encounter probably results in the observed high frequency of spermatangia-bearing males in this species. Apparently, the costs involved in losing sperm to another male are smaller than the costs of developing sex discrimination and courtship, or of not mating at all. This behaviour further exemplifies the ‘live fast and die young’ life strategy of many cephalopods.

I prefer to think of it as a brief happy life spent writhing constantly, passionately in the arms of love.

Hoving HJT, Bush SL, Robison BH (2011) A shot in the dark: same-sex sexual behaviour in a deep-sea squid. Biol. Lett. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0680.

(Also on Sb)

The story so far: Mario Beauregard published a very silly article in Salon, claiming that Near-Death Experiences (NDEs) were proof of life after death, a claim that he attempted to support with a couple of feeble anecdotes. I replied, pointing out that NDEs are delusions, and his anecdotal evidence was not evidence at all. Now Salon has given Beauregard another shot at it, and he has replied with a “rebuttal” to my refutation. You will not be surprised to learn that he has no evidence to add, and his response is simply a predictable rehashing of the same flawed reasoning he has exercised throughout.

In his previous sally, he cited the story of Maria’s Shoe, a tall tale that has been circulating in the New Age community for decades, always growing in the telling. This story is the claim that a woman with a heart condition was hospitalized, and while unconscious with a heart attack, her spirit floated out of the coronary care unit to observe a shoe on a third-floor ledge. As has been shown, she described nothing that could not be learned by mundane observation, no supernatural events required, and further, that the story is peculiarly unverifiable: “Maria” cannot be found, not even in the hospital records, and no one has been found who even knew this woman. The entire story is hearsay with no independent evidence whatsoever.

Beauregard attempts to salvage the story by layering on more detail. The description of the shoe was very specific, he says, right down to the placement of the laces and the pattern of wear, and she could not possibly have learned this by overhearing staff talking about it because “it would have been difficult for Maria to understand the location of the shoe in the hospital and the details of its appearance because she spoke very little English.” This is a curious observation; the claim is that she could not understand a description of the shoe, but she was able to describe the shoe herself to a woman, Kimberly Clark Sharp, who did not understand Spanish.

“When I got to the critical-care unit, Maria was lying slightly elevated in bed, eyes wild, arms flailing, and speaking Spanish excitedly,” recounts Sharp. “I had no idea what she was saying, but I went to her and grabbed her by the shoulders. Our faces were inches apart, our eyes locked together, and I could see she had something important to tell me.”

The question isn’t whether a seriously ill woman with poor command of English could see the shoe; it’s whether a healthy, ambulatory, English-speaking woman who has made a career out of the myth of NDEs could see the shoe. Beauregard’s additions to the anecdote do not increase its credibility at all.

Beauregard adds another anecdote to the litany, the story of another cardiac patient who was resuscitated and later recounted seeing a particular nurse while his brain was not functional. Seriously — more anecdotes don’t help his case. He threatens to have even more of these stories in a book he’s in the process of publishing, but there’s no point. He could recite a thousand vague rumors and poorly documented examples with ambiguous interpretations, and it wouldn’t salvage his thesis.

This new anecdote is more of the same. The patient is comatose and with no heart rhythm when brought into the hospital; over a week later, he claims to recognize a particular nurse as having been present during his crisis, and mentions that she put his dentures in a drawer.

I am underwhelmed. I must introduce Beauregard to two very common terms that are well understood in the neuroscience community.

The first is confabulation. This is an extremely common psychological process in which we fill in gaps in our memory with fabrications. I described this in my previous response, but Beauregard chose to disregard it. The patient above has a large gap in his memory, but he knows that he existed in that period, and something must have happened; he knows that he was resuscitated in a hospital, so can imagine a scene in which he was surrounded by doctors and nurses; he knows that his dentures are missing, so he suspects that someone put them somewhere, likely one of the people surrounding him during the emergency. So his brain fills in the gap with a plausible narrative. This whole process is routine and unsurprising, and far more likely than that his mind went wandering away from his brain.

The second term is confirmation bias. Only positive responses that confirm Beauregard’s expectations are noted. The patient guessed that a nurse he met during his routine care was also present during his episode of unconsciousness, and he was correct. What if he’d guessed wrongly? That event would be unexceptional, nobody would have made note of it, and Beauregard would not now be trotting out this incident as a vindication of his hypothesis. This is one of the problems of building a case on anecdotes; without knowledge of the range and likelihood of various results, one can’t distinguish the selective presentation of chance events from a measurable phenomenon.

While unaware of basic concepts in science, Beauregard seems to readily adopt the most woo-ish buzzwords. His explanation for this purported power of the mind to exist independently of any physical substrate is, unfortunately and predictably, quantum mechanics. Every charlatan in the world seems to believe that attaching “quantum” to a word makes it magical and powerful and unquestionable. I have to accept Terry Pratchett’s rebuttal: “‘Let’s call it Quantum!’ is not an explanation.” And neither is Beauregard’s feeble insistence that the universe possesses quantum consciousness, that psychic powers represent quantum phenomena, or that there is an infinitely loving Cosmic Intelligence.

Beauregard then accuses me of having an ideological bias, and that I’m a fanatical fundamentalist. He, of course, is the dispassionate, objective observer with no axe to grind, only interested in reporting the scientific facts. Unfortunately, his book The Spiritual Brain reveals to the contrary that he has some very, very strange beliefs.

“Individual minds and selves arise from and are linked together by a divine Ground of Being (or primordial matrix). That is the spaceless, timeless, and infinite Spirit, which is the ever-present source of cosmic order, the matrix of the whole universe, including both physics (material nature) and psyche (spiritual nature). Mind and consciousness represent a fundamental and irreducible property of the Ground of Being. Not only does the subjective experience of the phenomenal world exist within mind and consciousness, but mind, consciousness, and self profoundly affect the physical world…it is this fundamental unity and interconnectedness that allows the human mind to causally affect physical reality and permits psi interaction between humans and with physical or biological systems. With regard to this issue, it is interesting to note that quantum physicists increasingly recognize the mental nature of the universe.”

If I am an ideologue, it’s only in that I demand that if you call something science, it bear some resemblance in method and approach to science, not mysticism. Beauregard insists on trying to endorse the babbling piffle above as science by reciting the number of publications he has made, and how much grant money he’s got, when I’m looking for verifiable, reproducible, measurable evidence.

I would also remind him that Isaac Newton, who was probably an even greater scientist than the inestimable Beauregard, wasted much of his later years on mysticism, too: from alchemy and the quest for the Philosopher’s Stone, to arcane Biblical hermeneutics, extracting prophecies of the end of the world from numerological analyses of Revelation. While his mechanics and optics have stood the test of time, that nonsense has not. That his mathematics and physics are useful and powerful does not imply that he was correct in his calculation that the world will end before 2060 AD; similarly, Beauregard’s success in publishing in psychiatry journals does not imply that his unsupportable fantasies of minds flitting about unfettered by brains is reasonable.

(Also on Sb)

You may recall that tantalizing photo of an octopus eating a seagull that I posted last month: now the whole series and the story behind them is online.

My favorite argument against Intelligent Design is the fact that the clitoris is located nowhere near the cervix — for women, reproduction and recreation are fairly effectively uncoupled. But that doesn’t stop some people from imagining the existence of a vaginal source of sexual pleasure, the G-spot. I don’t believe it exists; I do believe that individuals can be sexually stimulated by contact in all kinds of places, from vagina to toes to neck to belly-button, that it varies from person to person, and that you don’t need to find an excuse in sloppy anatomy to justify what makes you feel good.

But I also think it’s an interesting example of chance and contingency in evolution. It would optimize the likelihood of reproduction if women could only find sexual gratification by stimulation deep in the vaginal canal — they’d be more likely to encourage sexual penetration. But the homologous tissue to the penis in women is the clitoris, which is in a fine position for creative external stimulation, but less than optimal for stimulation during intercourse. It’s location is clearly the result not of selection for the function of encouraging female orgasm during reproduction, but as a byproduct of selection for males’ interest in penetration during sex (females have sensitive clitorises because males have sensitive penises), which does enhance reproduction.

So it’s a good article highlighting a weird masculine desire for the vaginal orgasm, but it also illustrates that a fortuitous feature of female anatomy isn’t there for baby-making: it’s there for fun. O happy kludge, I’m so glad you’re there.