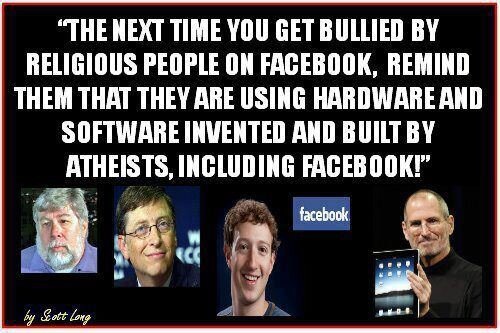

I got briefly drawn into a twitter argument with a fellow atheist who proudly flashed this image:

The next time you get bullied by religious people on facebook, remind them that they are using hardware and software invented and built by atheists, including facebook!

That is embarassingly bad. And when I pointed out a few of the flaws in that claim (briefly, ala twitter), he just repeated the claim and then accused me of trolling.

Look, it’s a terrible argument. It annoys me in multiple ways.

-

Have you ever heard Christians claim that all of science is built on a Judeo-Christian foundation? I sure have (WARNING: Creationist video on autoplay at link!). I’ve been told many times that Newton didn’t believe in evolution. It sounds stupid when they say it, it sounds stupid when atheists say it.

-

What, do you really think there are no religious scientists and engineers? Tim Berners-Lee is a Unitarian Universalist. Guglielmo Marconi was both a Catholic and an Anglican. James Clerk Maxwell was a Baptist. I mean, seriously, you’re going to claim our modern technological world is the product of atheists, and you’re going to ignore Maxwell? Jebus. Pretty strong selection bias you’ve got there.

-

I die a little bit inside when you tell me that your paragon of techno-atheist excellence is Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook. Who thinks that Facebook was something that couldn’t possibly have been invented by a devout Christian?

-

All anyone needs to do is cite one Christian who worked on the development of the internet, and your argument dies. Is it wise to stake your claim to something all it takes is one counterexample to shoot down?

-

I notice all the exemplars in the picture are white men. Keep using this logic; let’s start bragging to everyone on the internet that they are using hardware and software invented and built by white people. It’s the same argument. Do you see the flaws yet?

-

We are living in an interesting little bubble of time in which our best educated, most economically stable people are drifting into more secular ways of thinking. Odds are that if you’re sufficiently secure economically that you can go to Harvard in a tech field, even so secure that you can drop out of Harvard, you’re also likely to be secular or liberally religious, and you’re also more likely to be white. Do not confuse cause and effect. You are succeeding because being godless and pale-skinned gives you an edge — you’re looking at people who started out on third base. It’s not because being godless gives you special science powers.

You are not going to find many people who are more adamant than I am that religion and science are incompatible — they are fundamentally different ways of determining the validity of truth claims, and one works while the other perpetuates garbage — but I am not going to confuse that with an incompatibility between religious people and science. Scientists who are religious are quite capable of setting aside supernatural beliefs to work well and succeed in the lab. Being an atheist doesn’t turn you into a scientist or engineer. Avoiding church doesn’t make you a better scientist or engineer — practicing science, no matter how silly the hobbies you practice in your spare time, does that.