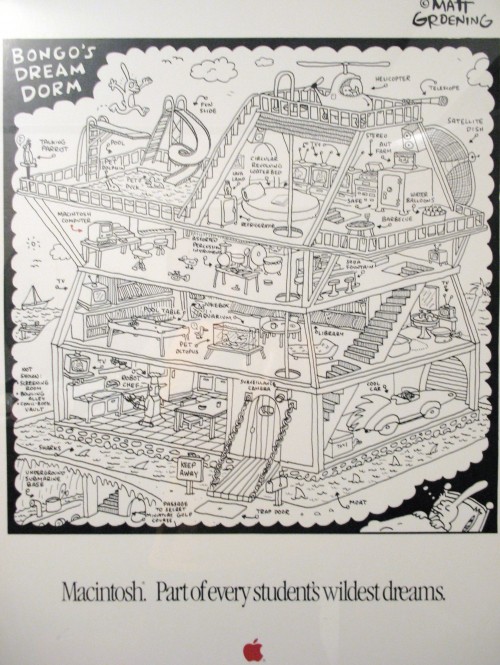

Back in the dim dark distant days of yore, Matt Groening actually did some promotional artwork for Apple — all at about the same time he started up with some little show called the Simpsons, and when he’d apparently doodle up a poster for them for the price of a Laserwriter.

Speaking of Groening and the Simpsons, Richard Dawkins will be making a cameo voice appearance this Sunday. Tune in!