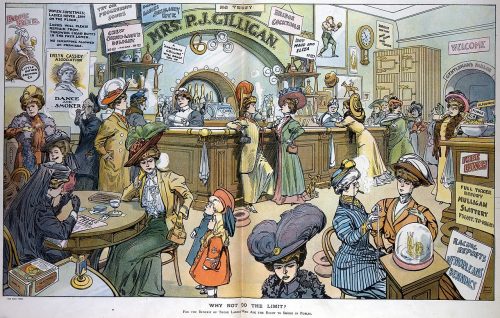

In 1908, Harry Dart was commissioned to produce an image of what horrors would be produced by the suffrage movement. I guess he succeeded?

Apparently, the worst thing he could imagine was that women might do the very same things men did all the time. I’m supposed to recoil from this unthinkable future…but it’s just fascinatingly detailed.