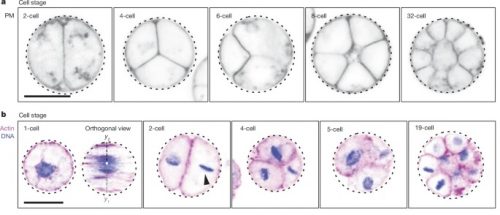

I know that a pile of bones of Tyrannosaurus or Triceratops gets all the attention and popular press, but what gives me a thrill is seeing a well-preserved Cambrian invertebrate, especially if it represents an early developmental stage. Here’s a real beauty, the phosphatized larva of Youti yuanshi, from Yunnan, China.

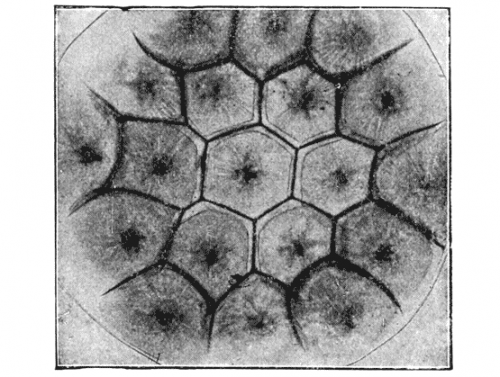

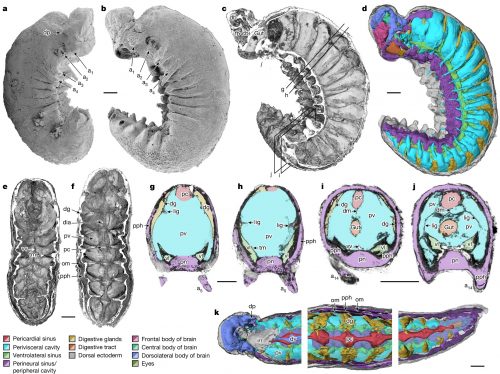

YKLP 12387. a, External scanning electron microscopy, right side. Damage to posterior epidermis exposes lining of perivisceral cavity, demonstrating blind gut. b, External scanning electron microscopy, left side. c,g–j, Median virtual dissection from X-ray computed tomography (XCT) data (c), showing location of transverse slices intersecting digestive glands (g,i) and transverse membrane (h,j). d, Semi-manual segmentation of internal chambers from XCT data, viewed from the left side. Dorsolateral aspects of the peripheral cavity are omitted for clarity. e,f, Virtual dissection parallel to coronal plane, looking ventrally (e) and dorsally (f), showing digestive glands, pericardial sinus, transverse membranes within perivisceral cavity, and oblique membranes within peripheral cavity. g–j, XCT sections at positions indicated in c at position of digestive glands (g,i) and at position of ventrolateral lacunae and transverse membrane (h,j). g,h, Sections close to the anterior trunk, reflecting segments at late developmental stage. i,j, Sections close to the posterior trunk, showing superior preservation of internal tissue. k, Segmentation of internal chambers from XCT data, viewed from the dorsal perspective at anterior, middle and posterior trunk. Aspects of peripheral cavity are omitted for clarity. a, appendage; cb, central body of brain; db, dorsolateral body of brain; dia, diagenetic grain; dg, digestive gland; dm, dorsal membrane; dp, dorsal projection; dv, dorsal vessel; fb, frontal body of brain; irr, irregular chamber; lig, ligament; om, oblique membrane; pc, pericardial sinus; pph, peripheral cavity; pn, perineural sinus; pv, perivisceral cavity; tm, transverse membrane; vl, ventrolateral sinus; vv, ventral vessel. Scale bars, 200 μm.

Superficially, it looks like a grub you might dig up in your garden, but this was found in marine sediments and was less than 4mm long, so you’d be unlikely to find anything like it today. It’s from a paper titled Organ systems of a Cambrian euarthropod larva by Martin R. Smith, Emma J. Long, Alavya Dhungana, Katherine J. Dobson, Jie Yang & Xiguang Zhang. The specimen is so well preserved that it can be studied at the level of organs and organ systems.

The Cambrian radiation of euarthropods can be attributed to an adaptable body plan. Sophisticated brains and specialized feeding appendages, which are elaborations of serially repeated organ systems and jointed appendages, underpin the dominance of Euarthropoda in a broad suite of ecological settings. The origin of the euarthropod body plan from a grade of vermiform taxa with hydrostatic lobopodous appendages (‘lobopodian worms’) is founded on data from Burgess Shale-type fossils. However, the compaction associated with such preservation obscures internal anatomy. Phosphatized microfossils provide a complementary three-dimensional perspective on early crown group euarthropods, but few lobopodians. Here we describe the internal and external anatomy of a three-dimensionally preserved euarthropod larva with lobopods, midgut glands and a sophisticated head. The architecture of the nervous system informs the early configuration of the euarthropod brain and its associated appendages and sensory organs, clarifying homologies across Panarthropoda. The deep evolutionary position of Youti yuanshi gen. et sp. nov. informs the sequence of character acquisition during arthropod evolution, demonstrating a deep origin of sophisticated haemolymph circulatory systems, and illuminating the internal anatomical changes that propelled the rise and diversification of this enduringly successful group.

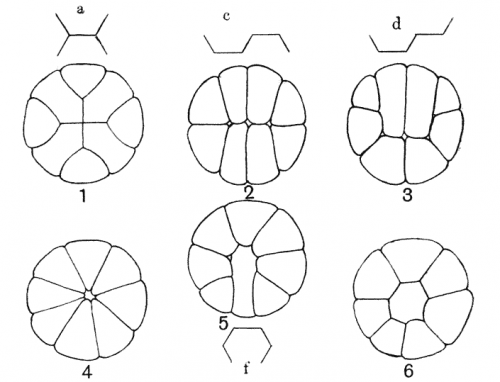

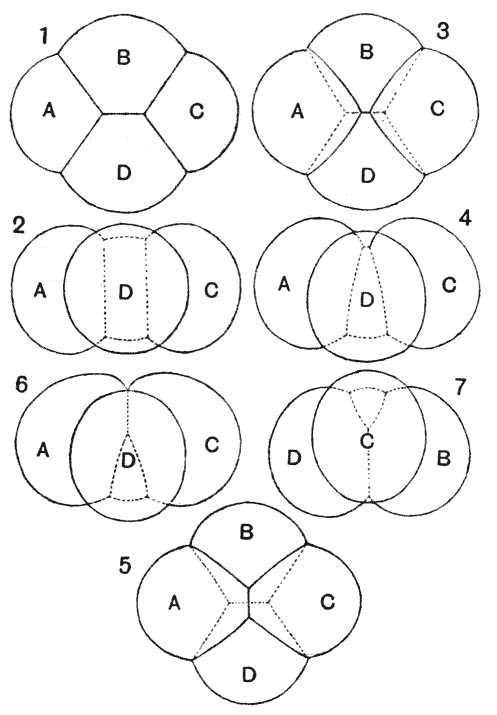

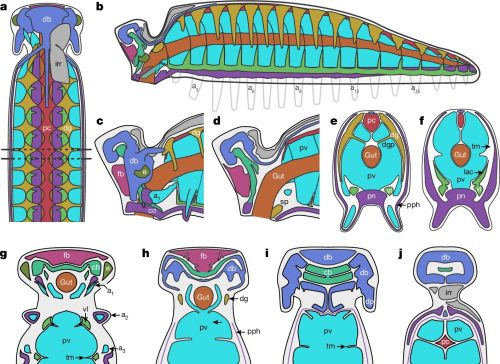

Here’s a helpful diagram to help sort out what’s going on inside the worm.

a, Organ system disposition in sagittal view. Dotted lines denote location of sections shown in e,f. b, Organ system disposition in transverse view. c,d, Head, from lateral perspective (c) and as medial transverse section (d). e,f, Transverse sections through trunk at location of digestive glands (e) and transverse membranes (f). g–j, Coronal sections through head, from ventral (g) to dorsal (j) planes. Colour scheme as in Fig. 1.

Most interesting is the comparative analysis with other Cambrian organisms, especially with regards to the organization of the nervous system.

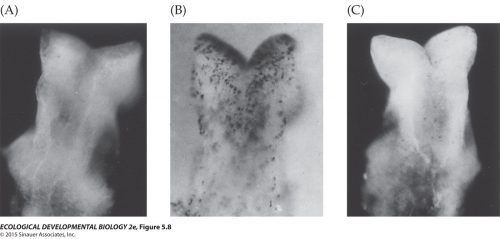

Phylogenetic analysis situates Youti yuanshi within the AOPK clade containing Anomalocaris, Opabinia, Pambdelurion and Kerygmachela. Under our preferred model, the circumoral brain ring of cycloneuralians corresponds to the panarthropod prosocerebrum, which innervates the first appendage pair (onychophoran antennae, tardigrade stylets or euarthropod labrum). We interpret the archicerebrum as a distinct development dorsal to the prosocerebrum, associated with sensory receptors: specifically the eyes, and the dorsal projections (Kerygmachela rostral spines, tardigrade cirri, crustacean frontal filaments or anterior paired projections of stem euarthropods; homology with the anteriormost onychophoran lip papillae is plausible, but may not be parsimonious). The taxa depicted in this figure are selected in order to depict the evolutionary context of Youti; the relationships shown are recovered under all analytical conditions.

Over half a billion years ago, the oceans were filled with diverse wormlike animals that were exploring different arrangements of their squishy bits — it was a complex ecology and every individual discovered should fill us with awe. Each of these forms has a deeper history that we need more fossils to decipher.