There was something else that bugged me in that odd claim from Ben Radford that girls would just naturally like pink better than boys: it was the terrible evpsych rationale for it that just made no sense.

First was the argument that blue has always been associated with boys, and pink with girls, and therefore it was only natural to sustain the distinction.

The choice of blue for infants has its roots in superstition. In ancient times the color blue (long associated with the heavens) was thought to ward off evil spirits. Even today the tradition continues; in many parts of the world people paint their doorways and window frames blue. Originally [“Originally”? Like in Homo erectus, or are we going back to australopithecines?] only boys were swaddled in blue [apparently, no one cared if girls were possessed by evil spirits. By the way, what color were they swaddled in, “originally”?], and girls were later assigned the color pink for reasons that aren’t entirely clear. But the color distinction between the two genders dates back millennia [Oops. See below].

But what about pink toys for girls? It’s an interesting question, and there are several answers. One obvious reason is that dolls are by far the most popular toys for girls [And boys like fire trucks and little red sports cars and setting things on fire, so they ought to like red]. What color are most dolls? Pink, or roughly Caucasian skin-toned [Girls should favor beige, then]. There are, of course, dolls of varying skin tones and ethnicities (the popular Bratz dolls, for example, have a range of skin tones). But since most girls play with dolls, and most dolls are pink (a green- or blue-skinned doll would look creepy [And brown would be just horrible]), it makes perfect sense that most girls’ toys are pink [So their ovens and cooking utensils and cleaning tools and cosmetics all match their dolls’ complexions? That doesn’t make sense, that’s just weird].

Eh, what? The color distinction goes back millennia? Since when was 70 years equal to millennia?

The march toward gender-specific clothes was neither linear nor rapid. Pink and blue arrived, along with other pastels, as colors for babies in the mid-19th century, yet the two colors were not promoted as gender signifiers until just before World War I—and even then, it took time for popular culture to sort things out.

For example, a June 1918 article from the trade publication Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department said, “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boys, and blue for the girls. The reason is that pink, being a more decided and stronger color, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl.” Other sources said blue was flattering for blonds, pink for brunettes; or blue was for blue-eyed babies, pink for brown-eyed babies, according to Paoletti.

In 1927, Time magazine printed a chart showing sex-appropriate colors for girls and boys according to leading U.S. stores. In Boston, Filene’s told parents to dress boys in pink. So did Best & Co. in New York City, Halle’s in Cleveland and Marshall Field in Chicago.

Today’s color dictate wasn’t established until the 1940s, as a result of Americans’ preferences as interpreted by manufacturers and retailers. “It could have gone the other way,” Paoletti says.

Pink for girls is a convention of the baby boomer generation. We’ve only had a couple of generations since, and I don’t think there has been much selection pressure to generate a sex difference.

But let’s be charitable here. Maybe there actually is a sex difference in how men and women perceive the colors blue and pink; that we dress baby girls in pink isn’t causal, but a consequence of a bias in how men and women see the world. Maybe, just maybe, these color preferences are a byproduct of a more significant evolutionary bias. At least, if you’re an evpsych proponent you’d like to imagine so. Which leads us to Radford’s citation of an amazing evolutionary hypothesis from Time magazine.

According to a new study in the Aug. 21 [2007] issue of Current Biology, women may be biologically programmed to prefer the color pink—or, at least, redder shades of blue—more than men…. [Researchers] speculate that the color preference and women’s ability to better discriminate red from green could have evolved due to sex-specific divisions of labor: while men hunted, women gathered, and they had to be able to spot ripe berries and fruits. Another theory suggests that women, as caregivers who need to be particularly sensitive to, say, a child flushed with fever, have developed a sensitivity to reddish changes in skin color, a skill that enhances their abilities as the “emphathizer.”

Really? I read that and thought it had to be some invention of the journalist at Time, so I had to go find the original article, and no, that was taken straight from the paper itself. What disappointing tripe.

It is therefore plausible that, in specializing for gathering, the female brain honed the trichromatic adaptations,

and these underpin the female preference for objects ‘redder’ than the background. As a gatherer, the female would also need to be more aware of color information than the hunter. This requirement would emerge as greater certainty and more stability in female color preference, which we find. An alternative explanation for the evolution of trichromacy is the need to discriminate subtle changes in skin color due to emotional states and social-sexual signals; again, females may have honed these adaptations for their roles as care-givers and ‘empathizers’.

I weep for all the African children who died or failed to reproduce because the enhanced red sensitivity of their mothers’ brains was insufficient to compensate for the reduced contrast caused by the color of their skin; I pity the poor African adults who bumble about romantically, unable to read potential partners’ social-sexual signals as well as their European peers. It’s also sad that even European males are less able, and have less need, to read their fellow human beings’ emotional states.

The utility of being able to evaluate when fruit is ripe isn’t in question, and I can see where that is a likely factor in the evolution of our color vision. But both males and females have that ability; there’s no reason to think that females have been selected for a slightly stronger preference for red, and that there’s some deep biological cause for this preference that is found in women, but not their sons.

But hey, I’ve got the paper from Hurlbert and Ling, so let’s look at the data.

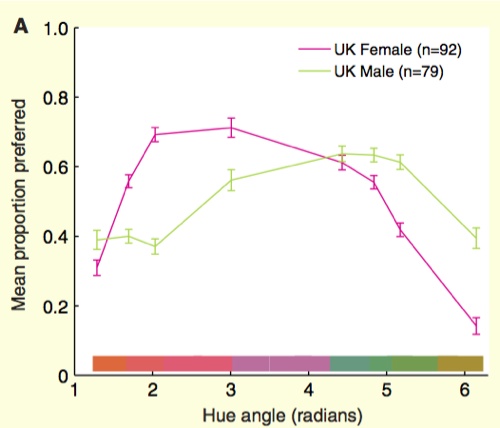

They do find a robust difference between the sexes in their study. It’s a simple experiment in which subjects are shown pairs of colored rectangles on a computer screen, and they are asked to select which of the two colors they like best. Do this many times, and you get a profile of favored colors. And what do you find? Most people like blue shades, but women tend to like a little more red in their colored rectangles.

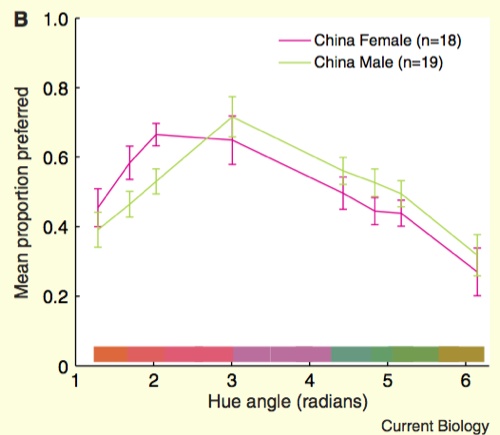

Now hang on, you might say — those data are all from British subjects, and there’s no way to sort out the accumulated cultural biases from the biology. Maybe those British women had been brought up by baby boomers who told them from babyhood on that pink was the color for girls, and so all we’re seeing here is a reflection of that bias. To correct for that, the researchers sought out native Han Chinese who were recent immigrants to the UK, and tested them separately. And look! They also show a consistent difference, with Chinese women showing more preference for reds than Chinese men!

From this, they somehow conclude that the differences are biological. If that’s true, though, they missed another major conclusion: compare the color preferences of Chinese men, in the bottom graph, to UK women, in the top graph.

One obviously must conclude that Chinese men have experienced a long history of selection for the ability to make finely tuned distinctions in the ripeness of fruit, to detect delicate blushes in the cheeks of their lovers, and to diagnose childhood diseases at the first flush. I’m impressed.

Oh, wait — there’s another possibility. Could it be that color preferences are actually affected by one’s culture? The researchers even admit this!

Yet while these differences may be innate, they may also be modulated by cultural context or individual experience. In China, red is the color of ‘good luck’, and our Chinese subpopulation gives stronger weighting for reddish colors than the British.

I see absolutely no evidence in the paper that the differences are innate, but lots of evidence that color preferences are plastic and responsive to environmental influences. Even the title of the paper looks wrong: it claims to find “biological components”, but nothing in the methodology or the results exhibits any way to separate biological components from environmental responsiveness.

It’s a fine collection of data, filtered by an unjustifiable evolutionary interpretation, processed yet again by a credulous journalist in a mass market magazine, and then regurgitated without question by Ben Radford. Sorry, guy, it’s bad science, and all you saw was the implausible unacceptable bit.

Hurlbert AC, Ling Y (2007) Biological components of sex differences in color preference. Curr Biol. 17(16):R623-5.

(Also on FtB)

Wouldn’t you know Ben Goldacre already addressed this paper back in 2007?

Radford doubles down. Ugh.