It’s always a boost to the self-esteem to hear how super-powerful-scary-awesome atheists are becoming. We have, apparently, been taking over the government, despite it being almost impossible to get an atheist elected to office.

Yet another theory that has been gaining traction and deserves serious consideration is that America’s massive science-industrial complex is attempting a most dangerous experiment. Since Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, we have seen a grave movement towards science-based strategic thinking in all forms of national policy. Whole swathes of government have been taken over by academic PhDs with an intense obsession with scientism. From the National Science Board to the Department of Education, from NASA to the National Institute of Standards, a powerful cadre of elite intellectuals is seizing control. A common thread amongst these activist bureaucrats is a love of science over God.

Fuck yeah, man, we have the National Institute of Standards!

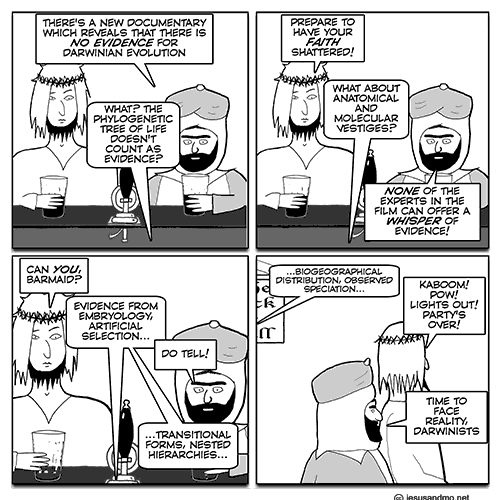

You may be asking yourself what we’re doing with this immense power. It was a secret, but this site has seen through to the awful truth and exposed us all. You know about the usual agenda:

President George W. Bush famously fought against the scientists entrenched in his administration. At many points they promoted evolution “theory” and “global warming” over good old-fashioned common sense. They tried to uproot Christianity in our schools through activist judges. And while President Bush fought the good fight, he ultimately did not win the battle. The long line of anti-theists ruling the inner halls of power since Lyndon Johnson remained in control.

Evolution and global warming are just the obvious distractions. Red herrings. Devious ploys to keep your eyes off the real assault by atheists on the American way of life.

That top secret mission, now revealed, is…chemtrails. We atheists are sending planes into the sky to spray a slimy haze all around the planet.

The American public has never quite grasped the purpose of all this spraying. Officials in the Obama administration have long refused to even talk about these efforts, though some have suggested that super spy Edward Snowden may leak details of this widespread project if forced against the wall by the international community. As we have seen with other government programs, the ultimate result here is not likely to be a beneficial one.

In various online communities there has been vigorous debate about what chemtrails actually mean. Some believe they spread barium as a highly-sensitive electromagnetic missile defense system. Others postulate they contain compounds that attack our blood cells and ultimately reduce populations, much like the fluoridation of our water supplies. The rise in disease and other unexplained medical phenomena does strangely coincide with the popularization of chemtrails.

Now you are asking, why would atheists be interested in hosing chemicals into the sky? You’re probably an atheist yourself, so you may find this difficult to grasp, but the goal is to poison all the angels.

Get the t-shirt!

So what is at the heart of this secret society of globalist atheism? One of their most significant concerns is the power of Faith. They despise the Glory of Jesus and the hope that He brings to countless Americans. The atheists are so insanely dedicated to their obscene cult they will try just about anything to destroy every remnant of Christian Love on this earth. As this sickening obsession was wed to advances in aerial spraying technology in the last century, one can surmise the evil compound that resulted. In this formula, it seems quite logical that the atheist’s next step would be to attempt the widespread murder of Jesus’s very Heavenly Agents of Love.

Angels. They are much more than a Christian bedtime story. They are much more than the sweet flutterings in the ears of believers. Angels are quite literally the factory workers of faith. They are tireless and everywhere. They accomplish innumerable feats, from minor pangs of guilt to the throbbing passions of love. The angels are there to guide us, to inspire us and, ultimately, to remind us of our obligation to Jesus. The fly through the air at His beckoning. They are gentle and ever willing. We would be far less human and humane were it not for the angels. And that is exactly why atheists fear the power of angels.

Atheists shake with contempt at the thought of love and decency. Their whole lives are dedicated to nothingness, to the gaping void of pain that nihilism defines. Indeed, atheists love pain. They love pain in their sexual rituals, in their drug addictions and in their secret globalist power schemes. Why do we have war? It’s the atheists who spread contempt of God and invite such reckless notions of communism and Islam.

Will Atheistic Science Annihilate Love and Prayer?

As secret atheist scientists in government pursue their goals of undermining Jesus in America, it only stands to reason that they would take their battle to the skies. The aerial dogfight is likely a vicious one. Who knows what advances they have made since the days of DDT and Agent Orange. Yet fight on they do, every single day! Our heavens are coated in a thick aerosol haze of spiritual hate and this nation’s faith is sinking.

I know some of you are going to browse that site and suggest that it’s a poe — that Hard Dawn is satirizing the far right wing. But think about it: that’s exactly what they want you to believe. And doesn’t that explanation make a heck of a lot of sense?