I got home lateish last night and just went to bed after a quick shower – a good end to a successful mission.

If you want more background about the quarry/pit I was working, there’s an article [newyorker] about a fairly cityfied journalist that went to the same spot and managed to find and shatter a pretty good trilobyte. Apparently this particular quarry is famous and was originally discovered by Charles Emerson Beecher in 1893. It’s from the same period as the more famous Burgess Shale, and has pretty much the same fauna, with the addition that the geologic conditions in the shale were right for pyritizing things. Atlas Obscura has some details about the history of the spot [atlas] and how it has changed hands over the years. I have to imagine that it’s hard to keep trespassers out (which is why I stripped GPS data out of the images]

I had not realized, until I was there for a while and was able to talk to Markus, my host for the day, that pyritized fossils aren’t just interesting because they look cool – the pyrite formation can preserve details of shapes that normally get lost. The petrified trilobytes from this particular pit have hugely important observable details under a microscope: scientists have observed eggs, nematodes in/on the trilobytes, as well as various exciting ancient activities of which the options are two: eating or having sex. Some of the trilobyte clusters from this region of shale have amounted to the Jeffrey Epstein of trilobytes (too soon?) parties frozen in mid-motion for millions of years.

The sheered surfaces of the stone are natural; to me it looks like it was cut with a machine. It’s all very fragile, though – you can stick a small hand-pick or rock hammer in, and just pull big chunks out. And that was the rest of my day. I sat on a nice pile of muddy shale rocks, and picked another spot of muddy shale rocks, pulled them out and ripped them apart, looking inside. Eventually and slowly my ass went completely numb, which I discovered only when I tried to stand up and wound up face-planting in the grave of the trilobytes.

You have to look inside the rock and not at the surface where it wants to break, because the fossils you’re looking for are lifeforms that got buried in sand/silt-slides and were preserved in their own private cavity in the rock. Anything that is on the surface gets washed away over the aeons. One of the other particularly valuable things about this shale bed is that the stone is very soft, so it’s comparatively easy to grit-blast the sand away and expose a fossil in all its detail.

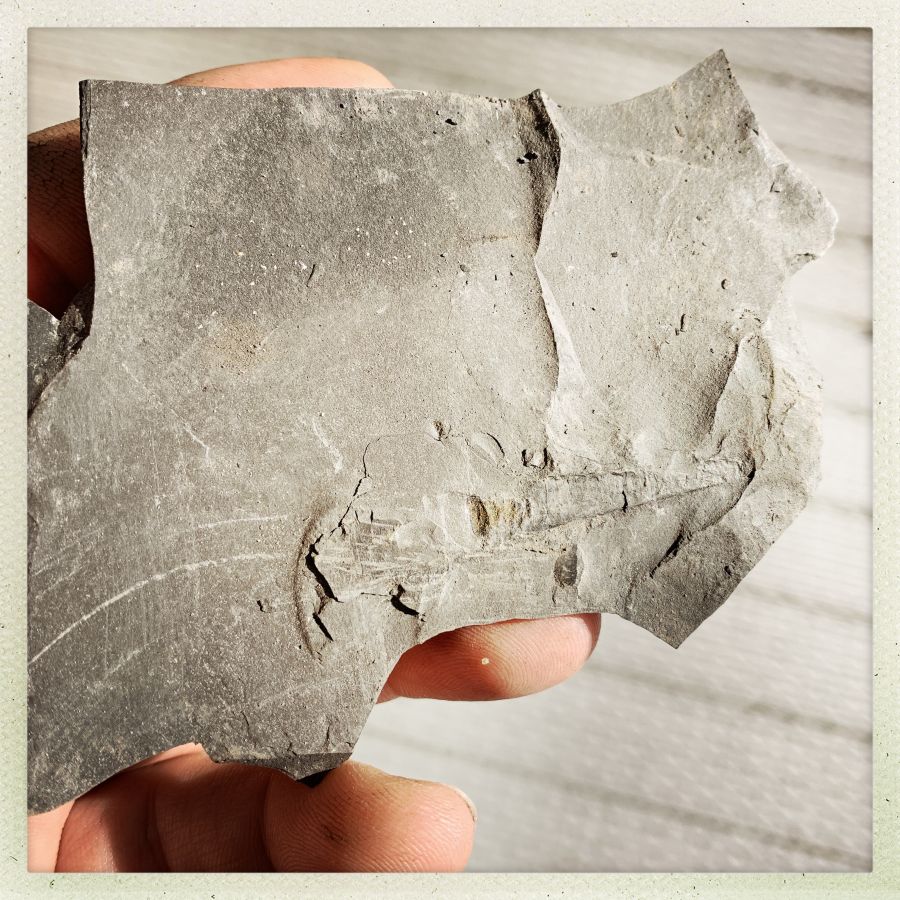

The surface looks sort of like pancake batter, poured on more layers of pancake batter, etc, etc. You can mostly pull it apart with your hands. The pancake batter look makes it especially easy to fool yourself by getting excited at something that appears to be an animal shape. Like that non-tadpole that’s sitting above the tip of my chisel; it’s just a bit of mud that got squeezed against another piece of mud, long ago.

I found a bunch of stuff that was uninteresting, or comparatively uninteresting. This pit is famous for its pyritized trilobytes, but people have also found lots of fossil sponges and cephalopods and even a few Pikaia Gracilens.

You sit with the rock on your knee and break little pieces off, looking at all of them from as many directions as you can, trying to find something unusual.

I did not know, for example, that trilobytes used to molt. There are lots of molted trilobyte parts but they are not considered “interesting.” Nor are the little sponges and cephalopods. Nor are the poop tracks. I got excited about poop tracks because: signs of life. Some creature, millions of years ago, crawled along that surface, and took a mighty waddling dump while it was doing so! Ah, the miracle of life!

All told I spent 5 hours picking apart a piece of rock that was about 2 cubic feet of volume. I could have covered a larger area, but less carefully, and I realized quickly that finding stuff is just a probability game. And you can’t just start hurling rocks around because you’ll miss stuff or break it.

I hadn’t realized how rare and valuable these pyritized trilobytes are – apparently a decently preserved one that has been cleaned up and reassembled (they often break) can fetch $1,500-$2,000 and there is a vigorous market for these sort of things. There are rockhounds who make a pretty good living digging fossils and cleaning them then selling them as artworks. So, once you find a piece of fossil, then the next step is to map that area and make sure you’ve got all the parts including the “negative” pieces of the cast.

Because the stone is quite wet, you have to wrap the rocks up in foil so they dry slowly or sometimes the fossils pop right out of the bed, and break. One of the fossil cephalopods that I found did that, already:

That’s some sort of relative of a bellemnite or ammonite – a snail without a curved shell. You can see the pointy part going off to the right, and the mess where the soft body parts were crushed near the opening of the shell. This is a “worthless” fossil given how many good ones have been found, but it’s mine so I kept it.

That’s what you’re usually going to be looking at. A load of shattered rock. But wait what’s that in the shadow?

I found 5 good specimens. Most of them are in one or two pieces but they’ll glue together easily. I left them with Markus, who has a couple of people who sit around with a grit blaster cleaning up trilobytes. It sounds like a lot of exacting, painful work.

I found 5 good specimens. Most of them are in one or two pieces but they’ll glue together easily. I left them with Markus, who has a couple of people who sit around with a grit blaster cleaning up trilobytes. It sounds like a lot of exacting, painful work.

Around 3:00 I started to get tired and I had a long drive home – about 5 hr. So I said my goodbyes and hit the road, stopped in Ithaca and had some yummy thai coconut/chicken soup, put Will Durant’s Story of Philosophy on my phone’s audiobook player, and the next thing I remember, I was home for a hot shower and crawling into my comfy bed.

That was a really interesting trip and I saw a lot of little pieces of rock up close and personal.

Markus mentioned that he also does annual runs out to Montana and other places where there are huge ammonite fields and stuff like that. I have to admit, it’s tempting. But I’m not sure I’m ready to start traveling again.

Fascinating and not quite what is imagined. I’m used to fossil hunting in harder east coast rocks. It sounds like a fun day, though, and I bet every one of the fossils you found was a nice hit of ’Fabulous!’

Great photos. Thanks for the field report.

How exciting, and congrats on your finds! Looking for rocks can be so much fun. I can understand being so absorbed you forget you’ve been holding perfectly still for a while and some parts have lost their blood supply.

We have a lot of rocks in our house. A lot. I think they are amazing and cool, and super fun to look for.

Oops, that should be ’not quite what I’d imagined.’

Could be of interest:

Fossil Shrimp With Five Eyes Could Be Elusive ‘Transitional Species’

I think one should not think about “worth” of a fossil. Remnants of life from millions of years ago. Just amazing!

You found some amazing fossils.

@ 5 avalus

Sometimes one has to consider the value to know just how strongly you need to defend the site from looters.

Thanks for the report, Marcus! I’m jealous. I took the kids fossil hunting a couple years ago, but the site where we went (a town literally named Fossil, Oregon) is famous for its fossils of vegetation, not animals & that’s all we found that day.

really cool, and thanks for the post!

I’m with avalus@5, and the market worth should be almost irrelevant to what you feel about it. Even if it’s a relatively common fossil, just that you personally found it on a trip and liked it enough to drag it home, means it’s got some personal value.

I never really tried any serious fossil hunting, but on amateurish and random geology trips, I don’t think I’ve stumbled across anything more interesting than some basic brachiopod shells or crinoid stem fragments. Maybe I’ll see about giving it a try at some nearby places on a future holiday weekend or something.

Also, belated happy Bday, and apologies about missing the main post, I had wandered away from FTB for a few days when you posted that…

If you search for “fossil pits near me” you have a good chance that there is someplace. The famous pits, like this one, or the Burgess Shale, are pretty tightly controlled (otherwise there would be people showing up with backhoes and filling the backs of trucks with rock to sort through elsewhere)

Nice haul.

We can hunt fossils here easily, there’s a whole mountain made up of discard from mining, but you mostly get ferns.

I would have been excited about the shit trail too. Sound like a good day and a good haul.

One of the places we used to go on holiday when I was very small was near Kimmerige Bay and Kimmeridge Ledges in Dorset, we always spent a day or two swimming off the shale and poking around for ammonites in the newly fallen rock. I have very happy memories of swimming in a sea that wasn’t freezing without getting sand in personal crevices or later in my sandwiches, but mostly of the exciting anticipation as a bit of shale was split by one of my rather older brothers. We did find treasures to take home, but while the shale was less soft that that which you were searching Marcus, it wasn’t that hard and over the years in a busy houseful of children the treasures were broken. Or possibly nicked by aforementioned older brothers … although as it was them that did the finding I suppose ‘nicked’ is harsh.

Very exciting, mjr!