The belltowers at Notre Dame are basically a medieval version of one of those barbecue charcoal-lighter cylinders. During the fire, you could see that the pompiers were trying to soak them down thoroughly. Apparently, they succeeded.

At one point, there was a picture of the left tower, with flames clearly shooting up between the floors. It’s the other tower that houses the great bells, including Emmanuel, a 13-ton bronze monster that was cast under the reign of Louis XIV. You may recall that bronze-casting was reaching its apex in Europe, as the cannons used by the Sun King’s empire were standardized, which led to their dominance on the battlefield under Napoleon Bonaparte.

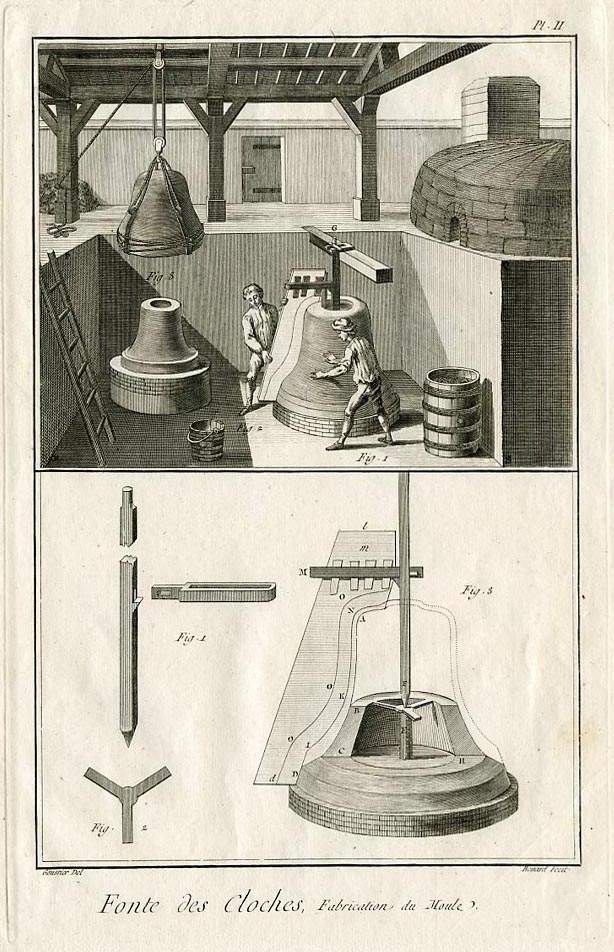

I was hoping to find an illustration of what it looked like when they installed the bells (Diderot’s Encyclopedia lets me down!) but it must have been quite a fraught undertaking. Presumably the floors of the tower were removed and a hoist was mounted at the top, then, it was wafted up to its resting-place.

paris Feb 2008

The bells of Notre Dame were(are?) beautifully tuned and make a characteristic peal that says “Paris” to me. The role of cathedral bells in history is fascinating – not only did they call the faithful and mark the hours, they were an alarm to call people back to the town’s walls if the English attacked, or the Germans, or the allied troops had liberated the city. On 9/11, they rang the bells in sympathy for the suffering that was going on in New York City.

Look at the dent the clapper made in the inner edge of the bell. That’s some sustained impact!

When I was a kid they used to have tours in the attic, the long gallery of wood that burned. This is going to sound stupid but I’ll say it anyway: it reminded me of a cathedral. Inside of a cathedral. Probably also a carpenter’s nightmare, though I can’t imagine any carpenter who built something like that could feel anything less than pride at the accomplishment. Some of the beams up there were as long as a football field; making the ‘frame’ consumed an entire forest. Now that they are talking about restoring the cathedral, I wonder where they will get the trees. The world has no trees like that, any more.*

paris Feb 2008

* Memo to entrepreneurs: tree farms are going to be big. And they’re pretty low effort. And they’re green.

* Memo to entrepreneurs: tree farms are going to be big. And they’re pretty low effort. And they’re green.

I looked at the picture of me and burst out laughing. That was when I was still in my “haul a camera bag” stage; I took a ton of gear with me everywhere I went. That bag probably weighed 25lb and hauling it up the stairs would have been a good workout.

Diderot’s Encyclopedie was a huge catalog of industrial processes. When I was a kid, pages from it would sometimes show up at rare bookstores, when some bastard broke apart a copy to sell individual plates. It must have been a hugely risky process and incredibly time-consuming to make that mold and heat and pour all that bronze.

I am sad for the bells. Will the heat have ruined the tone? I am glad some was able to be saved.

I am sad for the mosque in Jerusalem as well. I don’t appreciate religion but I do appreciate the art.

I’m more interested in a different artifact on the bell rather than the clapper scars (which seem pretty minor to me). But look at the scoop-out on the inner edge behind the clapper in the top pic. I’m guessing that was made as part of the tuning process.

Each of the bells has a name. If that’s the largest, it’s called Emmanuel and is tuned to F#.

Now I’m waiting for Christians to start saying, “The fact that the cathedral didn’t collapse after the fire is a miracle that proves God’s existence.”

A sad fact: if I google for “Notre Dame,” the second search result Google shows me is Trump’s tweet, “Perhaps flying water tankers could be used to put it out. Must act quickly!”

Firstly, this is so typical Trump’s behavior—he doesn’t know a thing about putting out fires, but he will still lecture firefighters anyway about how to do their jobs.

Secondly, the whole world already knows that Trump is an incompetent fool. Why give him so much attention? Why do search engines rank his silly tweets higher than actual information given by people who do understand a thing about fires and architecture and who also have information about what’s going on in Notre Dame right now?

I do not know about Notre Dame, but Oxford Colleges have found when it came time to renew the roofs of their dining halls that their forebears had thought for this need, and planted suitable oaks four hundred years earlier on college lands. Four hundred year old oaks ie in the prime of life, are about the age you need for such timber, if they are much older you start to lose the heart wood to rot. When there was a fire at Windsor Castle and such oaks were needed there was a nationwide appeal, more than enough of a suitable age were found. I can not believe that France a far less populated place than the UK does not have suitable trees.

Andreas Avester@#3:

Now I’m waiting for Christians to start saying, “The fact that the cathedral didn’t collapse after the fire is a miracle that proves God’s existence.”

God who, apparently, stood by with his arms crossed, watching the place burn. “That’ll teach them a lesson about my mercy! Ha!”

But you’re right; there are already images of the cross that hung over the altar, “miraculously” lit by the light pouring in the hole in the ceiling where the tower collapsed and punched through. God sure was on top of his smiting game yesterday.

Why give him so much attention?

Mockery’s got to be like a knife in his side, every time he moves around and sees that people really hate him and think he’s an ass. It conflicts with his narcissism. It’s what hurts him. Unfortunately, that’s all we have.

Andreas Avester @#3

Particularly as I understand that putting too much water on a fire can make a building collapse as they aren’t built to take the weight of completely sodden timbers, plaster, etc.

Jazzlet@#4:

I do not know about Notre Dame, but Oxford Colleges have found when it came time to renew the roofs of their dining halls that their forebears had thought for this need, and planted suitable oaks four hundred years earlier on college lands.

Lao Tze would approve. “When is the best time to plant a mighty oak? 300 years ago. When is the second best time? Today.”

I seem to recall reading somewhere (Massey, perhaps?) that the napoleonic wars depleted France and England’s supply of great beam timber, and a lot of wood was brought over from North America. It may be that there is nothing left. I’d try composites and stainless steel, personally. Set up a wood chip and resin feeder and make a great big 3D printer, print a roof.

The baby raping catholics will have a good excuse for trying to weasel out of reparations for their victims. Watch.

Jazzley@#6:

Particularly as I understand that putting too much water on a fire can make a building collapse as they aren’t built to take the weight of completely sodden timbers, plaster, etc.

By the time anyone could get an airplane and load it with water, the fire would have burned itself out anyway. Although, I would have been OK if they had done a low/slow pass in air force one and tossed Donald Trump out; perhaps he’d annoy the fire so much it’d go away. Probably just start a grease fire, though.

The paradox of dropping water on a fire is that it will only get to the fire if the roof has burned away and by the time the roof has burned away, it’s too late. Also, dropping water tends to turn it to mist, and if you’re low and slow enough that the water stays together while it falls, then you’ve just dropped weight like cinderblocks on a weakened roof. It works when you’re trying to suppress a forest fire because you want everything below the plane to get crushed and soaked, but that doesn’t apply for a building.

Marcus @#8

I mentioned over on Pharyngula that when York Minster had a fire in the south transept roof the firemen purposely dropped the roof in one co-ordinated drop to stop the fire reaching the bell tower, it also pretty much put the fire out.

I’ve also seen a chimney fire put out, at a neighbour’s house when I was in my teens. The neighbours were enormously impressed as the firemen put the fire out without any water reaching their rather beautiful sitting room, feeding just enough water down the chimney to douse the fire, but not enough to get beyond it.

Experts interviewed by France24 say there are no trees of the size (in France) needed to reconstruct the “forest” as it was. But — whilst it shouldn’t be rebuilt as “steel and glass” (to paraphrase one expert) — it’s unclear that it should be rebuilt in a similar way. That is an informed discussion which needs to happen in time…

blf@#10:

Glass, a la Louvre, would look amazing.

Random silly fact almost but not quite on topic: My burlesque name is “Belle Tower”. For real.

Marcus @#7

Among restorers there’s disagreement about whether you should always use authentic period materials or can you just substitute them with different modern stuff. My personal opinion is that it depends on the situation, sometimes there are very good reasons for using modern materials. But, in general, I tend to favor using authentic materials. Most importantly, I think that restorers should try to preserve original appearance. For example, in Latvia there’s an old building that got partially destroyed in the WWII and was supposedly rebuilt and restored to how it once was. It looks nice from the outside, but inside there are glass floors. In my eyes, such modern details clash with the otherwise historical look, and this kind of stuff ought to be avoided. I cringe each time I see ugly plastic windows in old buildings.

In Latvia, besides the usual problems like tight budgets, short deadlines, sloppy work, and cutting corners, there’s also the pesky problem that restorers often don’t really know how exactly some building looked like two hundred years ago. Let’s assume that there’s some 400 years old church that needs to be renovated. First decision is how exactly do you make it look like. The way it looked like when it was built? The way it looked like in 1800? The way it looked like in 1900? Each would yield a very different appearance. Let’s assume that you have settled for some time period. How do you figure out how exactly that building looked like in, let’s say, 1800ties? Many buildings got damaged during both world wars. Then there was the Soviet period, which was plain devastating for art and architecture. Soviet authorities didn’t just build ugly new houses and cities, they also destroyed old artworks and architecture. The end result is that when you enter some several hundred years old building, it bears little traces of how it once looked like. Thus restorers are forced to do lots of guesswork and they try to imagine how some building might have looked like. Occasionally they can try to remove all the new layers of wall paint and look at what’s hiding beneath it, but this doesn’t always work.

One of my former employers was a professional restorer who had worked in several churches (he hired me to work in a modern building, though). Some of the things he told me about the industry were just really sad. As a child I used to imagine that ancient buildings were restored to how they once looked like. Now I know that there’s lots of guesswork and sloppiness and the expectation that tourists who will visit some old church or castle won’t even notice all the flaws that they are seeing in front of their eyes.

By the way, my own interest in restoration was caused by my interest about historical art materials and techniques. Yet once I had learned about how artists made their pictures hundreds of years ago, I concluded that I prefer to use modern art materials. A significant portion of the old materials are simply inferior in quality, for example, many historical (and now obsolete) pigments are fugitive and have poor lightfastness, a few are toxic, some others make your painting surfaces crack, and then there were also some that were unethically sourced (like mummy brown or Indian yellow, for example).

Marcus @#10

I’m OK with the glass pyramid in front of Louvre, because that’s separated from the main building. But I wouldn’t be comfortable with an antique building getting some very modern-looking add-ons made from glass.

There are artists who proclaim that one should never mix together two separate art or architecture styles that originated in different time periods. I totally disagree with this claim. In my own artworks I frequently mix together all sorts of styles and influences. I believe that if some artist can combine two very different art styles and make the resulting artwork look cool, then that’s amazing.

Then there’s also the fact that artists and architects have combined different styles in a single artwork/building for millennia. For example, many castles and cathedrals were built for several hundred years, and that resulted with the upper part of the building looking vastly different than the lower part. And I’m perfectly fine with that.

Yet I still don’t like seeing modern-looking add-ons that are attached to old buildings. A restorer who’s working on a several hundred years old building shouldn’t install glass floors inside it. I would be perfectly fine with a new modern building that combines gothic architecture and glass floors, but I just don’t want to see that kind of things in old buildings. I think my distaste for such architectural changes stems from my respect for how the original artist/architect created the building. I believe that humans should respect the work of artists of past generations and not make any unnecessary modifications. I don’t know. Maybe I feel like this only because I’d be pissed off if I knew that some restorer who will live 400 years from now is going to modify my own artworks to look more modern. I don’t like it when other artists modify my finished artworks. I made my artwork the way I wanted it to look, and no modifications are welcome. At least not without first obtaining my permission.

I understand that buildings differ from paintings in the sense that people use them for centuries, and then modifications and repairs are necessary. If people actually live inside some building, then it’s impractical to maintain it exactly as it looked the day it was built. I can accept necessary modifications (for example, installing a modern heating system inside an old building). But I just don’t like unnecessary visual modifications.

When I was a child, we would make a single-use equivalent out of wax paper milk cartons. When the fire got started, the wax paper would also burn, thus distributing the charcoal.

@Jazzlet’s comment #4 likely derives from a story “often attributed to the anthropologist Gregory Bateson” but which I first read in Stewart Brand’s “How Buildings Learn”. New College used to have a page with a different description of the history, which I found via archive.org at https://web.archive.org/web/20020409132324/https://www.new.ox.ac.uk/NC/Trivia/Oaks/ . The most relevant part is:

“It is not the case that these oaks were kept for the express purpose of replacing the Hall ceiling. It is standard woodland management to grow stands of mixed broadleaf trees e.g., oaks, interplanted with hazel and ash. The hazel and ash are coppiced approximately every 20-25 years to yield poles. The oaks, however, are left to grow on and eventally, after 150 years or more, they yield large pieces for major construction work such as beams, knees etc.”

Yeah, the Louvre pyramid — which, incidentally is celebrating its 30-year anniversary this year — is brilliant; full credit to I.M. Pei et al. But I’m (currently) having a hard time imaging how something reminiscent would work on Notre Dame, including just what the point would be: That’s the roof, above the vaulted interior arches (which apparently are largely intact and probably why the exterior flying buttresses haven’t caused the walls to cave in), and not visible from inside (ignoring the damage caused by the collapse of the spire). Where something like that could work would be over the archeological vaults (catacombs) on the plaza outside in front of the bell towers, except should there really be a copycat pyramid in Paris?

I’m not welded to traditional materials, methods, or appearance; Have no suggestions per se; and Have no idea what the technical considerations might be. Clearly there was a feckton of wood up there, so there is scope for, e.g., a viewing “walkway” (that is, it could safely bear the load), albeit clearly whatever goes up must be weatherproof &tc. It is (er, was), after all, a roof.

(As an aside, the Louvre’s pyramid isn’t actually in front, it’s in the interior courtyard. And is also the main entrance, which was moved from the exterior (actual “front”, I think) as part of its construction. So yes, in a sense, you go “inside” (the grounds of the palace) to then enter the inside of the building. I’ve always though placing the entrance “inside” like that is one part of the genius of the design.)

Andreas Avester@13, Apparently, some years ago (in the 1990s as I now recall) there was a complete(?) laser survey done of Notre Dame, so there does exist a digital model. (This is from memory of what an researcher in the UK said yesterday.) That presumably will be very helpful whatever form the rebuilding takes. And it was last rebuilt around the 1850s, so there is a reasonable chance the plans &tc from then still exist. Yes, there will be guesswork and errors, but this isn’t a poorly-known facility out in the boondocks, however poorly-maintained it may have been.

Nothing a bit of engineered timber won’t fix. Mind you, I’m more interested in where all the lead went. In the Seine?

Andreas Avester @#14

What do you think about this solution https://www.landmarktrust.org.uk/search-and-book/properties/astley-castle-4806#Overview ? There is more information on the history and restoration pages. The Landmark Trust usually use traditional materials and techniques, but do not ‘age’ the repairs so it is absolutely clear what is old and what is new. Astley Castle was a huge departure for them, but was the only solution that anyone could come up with that wouldn’t have had the kind of problems you are talking about in the restoration of old buildings.

Andrew Dalke @#16

No, my father told me about it, he’d had it directly from the chap who’d found the relevant tranche of woodland who was, not surprisingly given how much money it saved the college, rather pleased with himself and boasted about it at a college dinner my father attended. According to my father the relevant chaps (it was all chaps of course) at his own college had promptly had a survey of their own woodland done for when they inevitably needed timber of such large dimensions for the hall or or chapel.

Jazzlet @#20 – it seems too coincidental that your father’s account aligns so closely to Brand’s widely told story concerning New College’s renovation back in the 1800s. Brand’s account is narrated at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YqH4eWR7jDQ wherein he cites Gregory Bateson as the source of the story. Bateson died in 1980 so the story must be older than that. In https://www.theguardian.com/politics/blog/2013/oct/02/david-cameron-oxford-college-trees-myth we read that David Cameron repeated the story in 2013, and also read that New College’s archivist Jennifer Thorp considers that story is a “myth”.

Now, to be specific, the “myth” is that the oaks were grown with the express reason of replacing the beams many hundreds of years later. The wood for New College did come from college lands. But you wrote “According to my father the relevant chaps .. promptly had a survey of their own woodland done”. As the archived New College page I referenced points out, there is an “annual review of College property, which goes on to this day (performed by the Warden)”, so the description you gave of needing to do a survey specifically to discover what oaks they have doesn’t match New College’s management style, and makes it seem like the other colleges have worse land management practices to not know they have had oak trees for several hundred years.

When did your father learn the story? Do you recall any other details, like which college it was or where the wood came from?

I am utterly charmed by the notion that the bell was “wafted”.

Jazzlet @#20

I don’t think I’m qualified to comment on the Astley Castle. I’m not familiar with the limitations people who restored this building faced nor do I know their reasoning for making specific decisions. The short page on restoration did say that many parts of the building were beyond repair, in which case what restorers chose to do seems reasonable.

I do think that restorers should try to use authentic materials and techniques whenever possible. Of course, practical constraints do apply. Let’s say you have to restore an old wooden window. Part of the window frame is rotten. You replace it with newly made details that look like the original ones and are made from pieces of old wood from the same tree species. Is some of the metal furniture missing? Then you look for replacements that are old and look similar to the original details. Window glass is also interesting. Old window glass is very thin, thinner than the glass humans make nowadays. At my home, I have old glass that’s only 2mm thin. When I wanted to buy new sheets of glass, I couldn’t find anything thinner than 3mm. More importantly, old glass isn’t perfectly flat. Instead its surface is wavy. It creates an interesting shadow pattern when sun shines through such glass. Thus people who restore old windows usually also try to source old glass. Except that it’s not always available, especially if you need large sheets of it. Old glass is so thin that it breaks very easily. While restoring my own windows, I accidentally broke several sheets of it. These are the kinds of practical constraints restores have. Alternatively, if you have to fix a brick wall, you will probably try to source old bricks from another building that was beyond saving. Of course, this isn’t always possible, in which case you must use modern bricks, and those look different from old and handmade ones.

These are the kind of reasons why I usually don’t judge restorers’ work unless I have detailed information about the object.

As for artificially creating a faux patina on the newly restored surfaces, I don’t have a strong opinion neither for nor against it. I’m fine with both options. The argument against faux patinas is that centuries ago, back when some item was originally made, it didn’t look old and didn’t have a patina, thus we are restoring some item to how it looked originally. The argument for artificially aging surfaces is that an old item might as well look old. It’s possible to create a faux patina on a lot of things—wood, metal, mirrors—you name it. My personal choice would be to create a faux patina if only a part of some item got fixed and looked different than the rest of it. For example, my old window frames had some parts of them that were rotten and had to be replaced. The wood I used for repairs looked lighter than the rest of the window frame. It depends on the species of wood, but generally wood gets darker as it ages. Thus I used a wood stain to make the newly repaired surfaces look darker and match the rest of the window. On the other hand, if some item was repaired in its entirety, I would probably abstain from creating a faux patina.

@Lofty #19

There was not much wind and the clouds were heading slightly to the west between Montparnasse and the Seine. It hasn’t really rained since then, so there is probably now a nice layer of lead(II)oxide (Marcus already pointed out the yellow color of the cloud) spread over the west of Paris. The Seine probably also got her fair share.

Take care,

nastes

Meet Colossus: The French Firefighting Robot That Helped Save Notre-Dame

Lofty@#19:

I’m more interested in where all the lead went. In the Seine?

Down? I suspect it was raining drops of lead in the cathedral, for a while there.

It would have melted pretty quickly in that blaze. By the time I saw pictures, the roof was already gone in the center and it was just blazing beams. Lead has a pretty low melting temperature. I’d expect the roof just sort of disappeared as the flames advanced.

I was looking at some of the battle photos and I noticed one fire crew was busy soaking down the area where the roof ended near the towers. They were on the ball: try to keep the heat from igniting the bell tower.

The French word for “firemen” is “sapeurs-pompiers” – sappers and pumpers. In the military, the “sappers” are the guys who get the worst of the shit jobs – they dig the ditches, lay mines, dig mines back up, assemble temporary fortifications, etc. They typically have a hellacious casualty rate. I’ve had a soft spot for the French sappers, since I read Bourgoyne’s account of the Berezina River crossing during the retreat from Russia in the napoleonic wars. That was some of the most epic doomed badassery ever. I noticed footage of some modern sappers fighting the fire, and they appeared to be wearing chrome dress helmets styled after the napoleonic issue. That probably says something about how fast they got into gear when the alarm went up – they were wearing their parade duds.

Andrew Dalke @#21

I honestly don’t know exactly when my father told me, but probably during my later teens, so that would be towards the end of the seventies. It could have been later than that, but I don’t think so. I have no idea which college he was dining at, it wan’t unusual for him dine out with collegues from other colleges, especially if it was some special feast, and then to return home to regale whoever was around with any tales that had amused him. I do seem to recall that the land from which the wood came wasn’t local to Oxford, but more than that nothing.

I don’t suppose his college actually needed to do a survey on the ground, but the relevant office holders may well have not previously paid that detailed attention to exactly what they owned as long as it was being appropriately managed, ie bringing in money, they tended to let the men on the ground get on with their jobs, occcasionally they issued instructions like “send Prof J a brace of pheasant”, but generally the role was more akin to department director, rather than the man setting the foresters daily tasks like harvest half the 150 year old oaks on that patch of land . It’s obviously the case that the colleges which survived the centuries did so in large part because of generous gifts by both their founders initially, and by their graduates over the intervening centuries, which included a variety of land under different uses including forestry. I guess if any gift had been as specific as ‘forest for the repair of the hall roof’ for any college someone would have piped up and displayed the evidence by now. However I do know some of the gifts were fairly constrained, but for the singing of masses for the donor (plus his wife, his children, his cousin three times removed etc depending on the level of generosity) in the chapel or for the support of ten poor scholars or whatever, as when circumstance changed there had to be some careful creative thought put into how they could hang on to the gift in the absence of say, the saying of masses for the dead after the reformation.

But saying all of this I am relying on my memory of what I was told, or gathered at least forty years ago, so I could be wrong about a lot of it, except that I know my father told me the tale. He was being rather unpleasantly smug about that being the kind of thing Oxford colleges did, so different from the way the rather younger universities I was applying to behaved.

Notre-Dame fire: How new tech might help the rebuild