What do you call it when someone wants more money, even proportionally tiny amounts, yet is willing to go to great lengths to get them? I’m surprised psychologists haven’t come up with a term for it, though I suppose it could be a manifestation of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

From Meet You In Hell [myh]

Though it might have been correct to say that [Frick] or Carnegie made no direct lobbying efforts, the steel industry as a whole was united in its efforts to uphold the tariffs that were being debated by presidential candidates Cleveland and Harrison. The issue was such a lightning rod in its day that a fair number of ordinary laborers were ready to forsake their natural Democratic leanings and vote for Republican candidate Harrison, a staunch supporter of the tariffs.

And despite such artful public dodging, the truth was that the amendments to the wage scale sought by Frick would have saved the company no more than two cents per ton on a product that sold for between thirty and thirty-five dollars per ton at the time. As Frick had pointed out in his own article, the changes would affect only the skilled craftsmen at the Homestead mill, less than one-quarter of the workforce. While the men paid at tonnage rate might earn somewhere between ten and fifteen dollars per day, the average rate for a laborer was in the neighborhood of $2.00 to $2.25.

Carnegie Steel, moreover, had become the nation’s leading producer of steel, its output soaring from 250,000 tons in 1880 to more than 1 million tons in 1890. As profits for that year totalled nearly $5 million, and a two-cents-per-ton write-off would have dented the bottom line by all of $20,000, it seems inexplicable that Frick and Carnegie would not have surrendered the point in a trice.

However, between 1889 and 1892, the period governed by the contract, steel prices had decline nearly 19 percent, despite record profits. In any case both Carnegie and Frick viewed concessions to labor not as justifiable compromise but as the setting of dangerous precedents sure to be seized on in other negotiations down the road. Carnegie’s view of labor costs was summarized in a letter he had written to Abbot in 1888 before the strike of that year: “I notice that we are paying 14 cents and hour for labor, which is above Edgar Thompson price. The force might perhaps be reduced in number 10 percent so that each man getting more wages would be required to do more work.”

In Carnegie’s mind, nothing had changed in the intervening years. If costs could be cut, then cut they must be, and never mind if the category read “minerals” or “vegetables” or “men.”

It is an interesting question, isn’t it, that an executive who was already fabulously wealthy, who ran a fabulously successful business, would stoop to argue over $20,000 dollars off the bottom line.

To be fair, the same question can be flipped around: $20,000 divided up among the workers wouldn’t have had much impact on them, either. But, since the business was bringing in $5 million profit Carnegie could have easily afforded to reduce that to, say, $2 million and offered benefits to the company’s workers that would surely have changed their lives dramatically for the better.

What is odd, to me, is that Carnegie and Frick were both penniless immigrants who came to America lacking education and opportunity – they were the same kind of people as the laborers that they were negotiating so hard with. In my mind, it would be like negotiating hard with a family-member, leaving them living on the edge of a financial precipice while I lived in a mansion. And, when Carnegie and Frick died they both were re-invented as “philanthropists” because they gave beautiful things to the country that nurtured them – excuse me – they gave beautiful things to the middle class and wealthy. The laborers? They put the screws to them for pennies.

What is the name of that disorder?

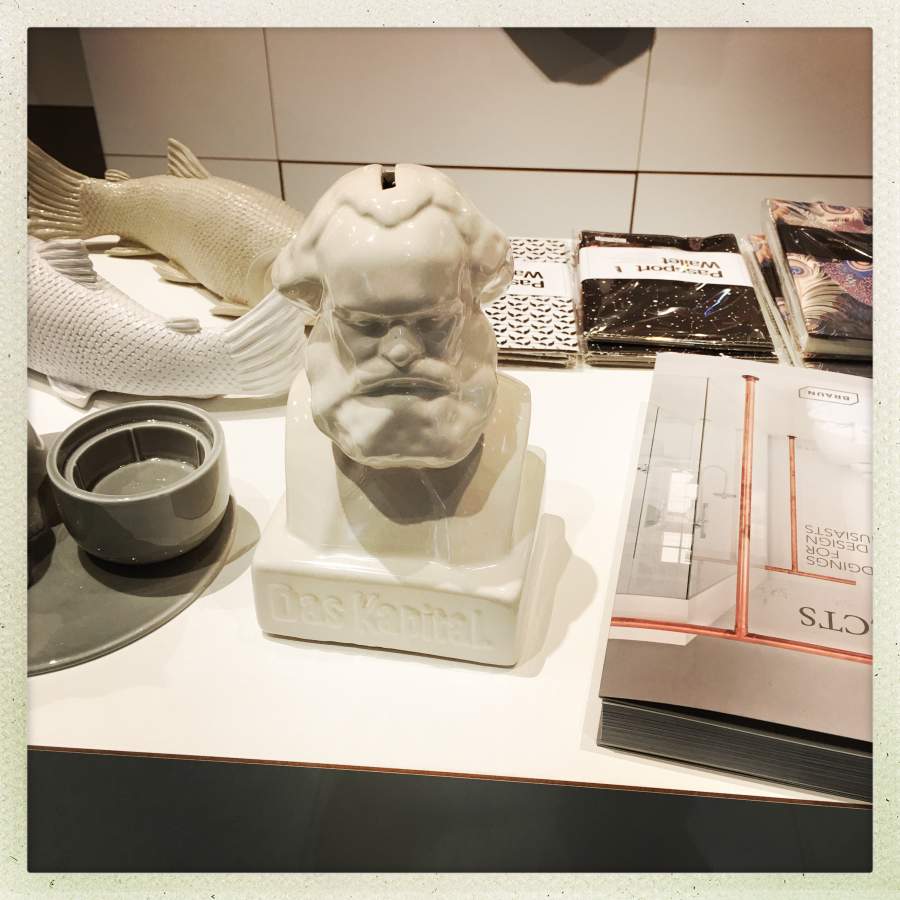

A thing I saw in Munich airport

At various times I have tried to slog my way through Marx’ Capital, mostly because I’ve tried to understand his dialectical method (and I feel like my fingers keep slipping off it…); between Marx and David Landes’ Unbound Prometheus and Meet You In Hell I have formed a view that there was a very important discussion going on beneath the early American industrial revolution. Marx’ focus on how we value commodities is an attempt to understand the cost-justification of, well, people like Carnegie. The question Marxian economics tries to answer, in this context, is “how much additional value have the laborers created in turning those tons of ore into tons of steel?” This is a vital and necessary question, because the industrial capitalist insists (rightly!) that without their factory and their investment in starting their business, there would be no work for the laborer, at all. Therefore, the capitalist is rightly a gate-keeper between raw ore and the value of the steel, and deserves to take a certain amount of the value of the laborer’s efforts for himself. Marx is trying to explain how we can figure out what all this stuff is worth, so we can then argue about whether the profits are being divided up fairly.

Jeff Bezos house: a great big collection of pennies

But because of the differential power-structure that already exists, “fair” is not ever on the menu. As we’ve seen, the industrialist can close the factory and starve out labor, if the industrialist was smart enough to set aside enough money to wait out the laborers. “Fair” only seems to happen when the capitalist is standing with a rope around their neck and the other end over the branch of a tree, and they suddenly realize they really love the workers that lifted them to such heights.

It seems to me that part of the reason capitalists were so upset by Marx is that he tried to lay out a way of discussing the balance of contributions in the system. And, it was clearly an unbalanced system – Carnegie and Frick were the Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates of their day. But, interestingly, Bezos and Gates were both smart enough to bring along with them a solid cadre that they made very rich, indeed. A cadre that can, like Carnegie and Frick did, sneer at the workers in the factories who are barely making ends meet while they work their asses off for the top of the power structure.

I try to think about these things and I try to see where people have sought to understand how that balance is built. But I keep coming back to the idea that there’s just something wrong with people like Carnegie, Frick, Bezos, Gates, Buffet, Ellison, etc. – they are comfortable taking pennies out of the pockets of the people who elevated them to great heights. What is the name of that disorder?

Epicurus said: [stderr]

Some men want fame and status, thinking that they would thus make themselves secure against other men. If the life of such men really were secure, they have attained a natural good; if, however, it is insecure, they have not attained the end which by nature’s own prompting they originally sought.

Epicurus would say, apparently, that the hyper-acquisitive are confused, that they have made a strategic mistake. Would a psychologist be able to look at Carnegie and Frick, who came to the US penniless, and say that they were suffering from a form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder that made them unable to rest until they had done everything they could to get all the money (safety from want) they could? This is a serious question. Why doesn’t psychology say that people like Carnegie and Frick are disordered?

- They are rich. Rich people are not “disordered” they are “eccentric.”

- Their obssession was beneficial to them. But that raises the question of whether their obssession was beneficial to others. Suddenly, it gets complicated.

- They are dead. We can’t psychoanalyze the dead.

Greed.

The word itself seems so harmless but the consequences are not.

Marcus:

You don’t stay rich by letting 20 grand walk out the door. Yeah, I know, they had more than they could ever spend, but that’s the reasoning underpinning it all. Wealth comes with paranoia; paranoia dictates hoarding every penny.

I grew up privileged on the money front. One of the things I frequently enjoyed were doing the rounds of thrift stores with my grandmother. Later, I tried to get Rick to go thrift store shopping, I hadn’t been in any of the ones in Long Beach before, and he refused. When I insisted on going in one, he waited outside. He grew up poor, and from his perspective, thrift stores stank of poorness and charity. When I finally got that out of him, I just stared for a bit, then said “it’s not poor people who shop thrift stores, it’s people with money.” That was quite the revelation to him, but people with money go hand in hand with being extremely reluctant to hand over as much as a penny.

kestrel@#1:

Greed.

The word itself seems so harmless but the consequences are not.

Yeah, but it’s too small-sounding. I guess like all labels, it’s circular.

I was thinking something more along the lines of: “Obsessive wealth disorder.”

Caine@#2:

You don’t stay rich by letting 20 grand walk out the door. Yeah, I know, they had more than they could ever spend, but that’s the reasoning underpinning it all. Wealth comes with paranoia; paranoia dictates hoarding every penny.

That’s close to Epicurus (and I agree with it) – people who desire wealth and power desire it in order to protect themselves from the vicissitudes of life; that means that when they finally get wealth and power they discover that there is no amount that will make them comfortable – the wealthier they get the more they have to protect.

Rich people are all about the slippery slope, “If I let them have 20 grand, then they’ll want 20 grand, then those will want 20 grand, and where will it end?”

Past that though, is the real root. There’s a reason for the saying “the rich are different.” With money comes power, the more money, the more power, and that’s the addiction, I think. You have an immense amount of control with immense amounts of money, and you can get away with practically anything. Heady stuff, that.

Caine@#5:

Being rich is, itself, a slippery slope. “If they manage to chisel $1 million, then next they’re going to want $10 million, and where will it stop?”

Greed is an appetite that grows with the eating.

I’m sure there’s something in the Tao about this, but I’m not at home right now and don’t have a copy handy…

Dunc@#7:

Chapter 3.

I’m not so sure about “keeping the people ignorant”

I don’t think it was entirely a matter of their personalities. Not a new idea here, but … as people were impressed by how much things snowballed during the Industrial Revolution, there was a big shift in the culture, toward being ever more efficient, parsimonious, meticulous, and so on. A lot of people at the time were fairly explicit and unapologetic about it.

Of course, some have always been like that (just a personality trait, I guess), but if you liked what modernity was bringing us (not everyone did), then you’d be inclined to think there is a deeper lesson to be learned from it. The model was maybe something like making a steam engine. You had better not do a half-assed job of that, letting little things like friction cause you a world of trouble. You had to be very precise and pay attention to lots of picky little details; then you’d have a machine that did some really marvelous things that people wouldn’t have dreamed of a few centuries earlier. If you don’t, the whole thing may just stop working altogether or blow up in your face.

Everybody else is doing it. That’s what you tell yourself, at any rate. And not doing it is the sort of small blunder which loses wars and makes whole countries fall behind the rest. But they really go all in with it. This shit has Biblical proportions; we’re talking human sacrifice, dogs and cats living together, mass hysteria.

Given how much things were changing so rapidly in the world around them, it could almost seem believable. That kind of thinking (along with lots of paranoia and cold-blooded greed, to be sure) can make you believe every last penny has just as much significance or that what you’re doing when you run a giant corporation is somehow analogous (even though that’s obviously false). You don’t tell yourself that it’s just a penny and shrug it off as no big deal, because you’ve already got it planted deep in your mind that you’re in some radically new type of situation that works according to a different set of rules.

In the case of penniless immigrants who became rich, there may be a component of PTSD to this mindless greed. Not that it excuses anything.

My grand-grandmother had been through a famine, and she was left with an irrational tendency to mend and hoard. If she broke a jar, for instance, she would tape it together. When my grandfather pointed out it would not be waterproof, she would say it could still be used to store, say, beans, or rice.

Maybe the industrialists who made through very hard times were never able to shake away their instinct to save money. Or maybe the same traits that allowed them to survive and prosper are the very things that make them so unpleasant once they control the livelihoods of thousands.

Or maybe they are just assholes without any empathy.

I often find that people who managed to rise above their disasvantaged group are the most blind to their own exceptional luck. You would not expect someone who won the lottery to say “oh, those peniless guys? Fuck ’em. I was once like them, and if I could win the lottery, so can they.” Yet that seems to be how a lot of the rags-to-riches individuals behave.

I’m a bit uneasy about categorizing disliked behaviours as mental illnesses. Even if we accept the whole premise of the DSM (and equivalent approaches), it glosses over how making it about the individual rather than society is profoundly disempowering. “It’s not any structural inequality that causes you distress, it’s you” can’t be but something that supports the status quo.

Pathologizing disliked behaviours tends to be useful for those in power anyway, considering how many people in the Soviet Union whose worldview was inconvenient were found to have a mental illness that required them to be locked away — for their own safety and well-being, of course.

(There is much to be said about the premise of the DSM and friends, but that’s not this discussion. I found https://thenewinquiry.com/essays/book-of-lamentations/ to be a insightful take on the approach underlying the DSM.)

That said, I think it’s close to Marcus@4. But there is not just that desire for their money/power to keep the vagaries of life at bay, though. There seem to also be a desire for power and recognition in their own right, as they’re all setting up their “charities” but doing so quite visibly… because just doing charitable works (unseen) doesn’t count. Paying more to the people who do the work that makes you richer means you have less money to either own or ostentatiously give away. Paying the labourers a good wage and ensuring they have health care and all that is not going to get library systems or schools name after you.

What’s interesting about this “compulsive wealth disorder” or greed or whatever you want to call it, is that it can lead to some very bizarre and contrary-to-your-best-interest behavior. Something the Partner calls “stepping over a dollar to pick up a dime”. Case in point: we knew the caretaker of a vacation home owned by this very wealthy guy. How wealthy was he? He remodeled his bathroom and it cost ONE. HUNDRED. EIGHTY. THOUSAND. DOLLARS. Why? Because he wanted the bathroom to be re-done with Italian marble, and oh yeah, the bathroom was on the second floor so the house had to be re-structured to bear the weight. So this same rich guy chewed out our friend who had been asked to replace all the hinges at the vacation home, so he had gone to the hardware store and picked out some really nice hinges that cost $3.50. The rich guy was livid and declared he would NEVER pay that much for hinges, take them back and get some cheaper ones! So our friend did. Leaving us all wondering WTF. Why would you not want the better hinges (not that costing more always equals better but it did in this instance)? Weird.

Now, this one got me thinking.

In German there’s a word Pfennigfuchserei, which gets translated as “miserliness, cheeseparing, niggardliness.” This is a compound word (Pfennig=penny; fuchsen=to annoy). The definition of Pfennigfuchserei is “exaggerated economy, scrupulosity, and pettiness in financial matters.” The word is used when referring to excessive greed going so far that the greedy person starts worrying about every single penny.

In German there’s also the idiom “einen Igel in der Tasche haben.” Literal translation: “to have a hedgehog inside your pocket.” The metaphor is that a person has a hedgehog in their pocket, therefore, whenever they put a hand inside their pocket to take out money, they injure their hand, and thus they are very unwilling to spend anything.

I could also think of Latvian and Russian words with similar meaning as the German Pfennigfuchserei, but those words were pretty boring (no interesting etymology or metaphors), so I won’t bother you with a list.

So, your argument here is that somebody who has personally experienced a specific type of misfortune in past should be more empathic towards those who are suffering the same type of misfortune now? I doubt that it really works like this when it comes to empathy. Granted, my understanding about empathy is purely theoretical, so I might not be the best person to judge this. Still, I know plenty of rags-to-riches stories, that didn’t end with the rich person helping (or even wanting to get associated with) the poor.

Laborers might as well insist (rightly!) that, without their work, there would be no profit and, in fact, no money at all for the capitalist who would become just some poor dude who has to work in order to make a living. Therefore, the laborer is rightly a gate-keeper between the capitalist and their profit. Now, at this point some people might argue that laborers are replaceable—if one laborer quits their job, the capitalist can just hire somebody else. But the factory owners and capitalists are also replaceable. In Atlas Shrugged, Ayn Rand cooked up a scenario where one capitalist quits, the factory ceases to exist, and then the whole modern world collapses, because nobody is manufacturing that stuff anymore. It worked in a novel, but this is not how it works in real life. If one capitalist closes their factory, somebody else will exploit the newly opened niche and they will open another factory somewhere else. Capitalists are just as replaceable as workers. If American businessmen don’t want to run steel mills while there is still a demand for steel in the world, another capitalist in China will seize the opportunity and open a new steel mill there.

Lack of gratitude, maybe? Shamelessness?

A consequence free life. The more money and power you amass, the less consequence there is for any given behaviour. Sometimes, consequence can be driven by large groups, but how much of a consequence is it really, for someone with obscene amounts of wealth, power, and handy connections?

I wouldn’t want a consequence free life for myself, because that would be a very bad thing where I’m concerned, but I can easily see the attraction.

Reading this blog post, at first I assumed that “compulsive wealth disorder” isn’t meant seriously, that you aren’t actually proposing an idea that being greedy is a psychological disorder. “Compulsive wealth disorder” seemed for me like figurative language that’s not meant to be taken literally.

But then bttb @#11 said, “I’m a bit uneasy about categorizing disliked behaviours as mental illnesses.” That’s something I wholeheartedly agree with: of course you shouldn’t cook up mental disorders every time you don’t like something. After all, the potential for abuse is immense here.

Anyway, so now I’m wondering, whether you were serious about the “compulsive wealth disorder” or not. Did I misunderstand something again? I’m already aware, that I have a tendency to completely miss figurative language and incorrectly interpret it literally. Am I also making the opposite mistake and seeing figurative language, where there is none?

By the way, some Soviet psychiatric diagnosis (like, for example, “sluggish schizophrenia”) were pretty interesting. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_abuse_of_psychiatry_in_the_Soviet_Union

Marcus, @#8: I believe that bit about “keeping the people ignorant” is one of those difficulties of translation… Hua-Ching Ni renders that verse as:

I was probably more thinking of 46: Wanting Less:

(I’m very much enjoying Le Guin’s version, but I don’t think I’d want it to be my only version… I think Master Ni’s version is in some ways clearer, if perhaps a little too wordy in places – although I should note that I’m not really qualified to judge who’s done the better job…)

As to whether this behaviour is disordered, or what constitutes “enough”… It’s worth remembering that all of us here are very wealthy by the standards of most people in the world today, and unimaginably wealthy by he standards of most people in history. It seems that for most people, “enough” means “just a bit more than I have right now”. On the other hand, I do think there’s a pretty strong argument that continuing to compulsively acquire and hoard wealth past the point where you have more than you could conceivably spend it all, or the point where any further increment could make any appreciable difference to your life, is almost certainly maladaptive.

(Reading back #16, I see that Master Ni’s version probably isn’t that much clearer when you’re trying to transcribe it on a smartphone after several drinks. Sorry.)

It’s not so much the wealth as the power that goes with it that gets the rich excited. Screwing a poor person out of a much needed $20 is as much of a thrill as cheating $1mil out of your industrial neighbour.

Dunc:

I can’t speak for other places, but in Ustates, acquisition should qualify as a disease, most likely an addiction. Everything here is based on acquisition, and ruthless competition. It’s all about living up to someone else’s standard. “Keeping up with the Joneses” and all that. It’s been that way here from the beginning of the invasion, and it’s embedded in the very foundation.

Too many people are not content with enough, meaning housing, food, a security cushion, and whatever you need to provide sprogs, if you have them, and enough to indulge in fun and hobbies, within reason. Amerikka doesn’t do content. Amerikka hates content. Being content with what you have and what you make brands you as unambitious and basically useless in a society that is furiously consumer driven, and what matters is all the material crap you can point to, no matter the size of your debt.

Caine:

Mmm. I once got a remarkably agitated and antagonistic reaction when I expressed my view that I was a sufficiently “good enough” person and therefore did not seek to strive to become a better one.

(Apparently, to some that attitude is restricted to material things)

Some is good.

More is better.

Too much is just about right.

machintelligence, that just means sufficiency is insufficient for you, which I consider perverse.

Your expressed sentiment is similar to that acted by the featured examples, for whom sufficiency didn’t suffice.

—

PS

Too much is just about right ∧ more than too much is too much → more than too much is just about right;

but then

More than too much is just about right ∧ more than more than too much is more than too much but still too much → more than more than too much is just about right

…

[There’s never enough!]

John:

I can’t even imagine being that way. I can’t live such a conclusion because I’m not a good person, so it’s always been an ongoing struggle to be anywhere near ‘good enough’. I don’t know how I’d ever be able to settle on a certain point where I felt I had grown and learned enough.

I take it the ‘remarkably agitated and antagonistic’ reaction was from me. Sorry, but I don’t remember it. There are a lot of things I don’t talk about in any sort of depth, and this particular subject would be one of them because I can’t clarify it well without getting extremely personal.

Caine, your attitude is fine, too.

re

Oops. No. Sorry, did not mean to suggest that at all.

(FTIW, I got booted from a secret FB book forked from the original Pharyngula FB group thereby — years ago, now)

Works best on fossils.

If one is an actual living thing, then one had better be responding to ones current challenges.

chigau, well yes, but if responsiveness is necessary, then sufficiency requires responsiveness.

A good friend of ours though that we were poor because we didn’t have a big house, or go travelling overseas every year and never had new cars. I told her cheerfully that we weren’t actually poor as the house was paid off, we had adequate money in the bank for our needs and we were quite happy to live within our modest income. Boundless greed is not for us. I shudder when I see it in other people.

Caine @ #20:

It’s that “within reason” that I’m struggling with at the moment… Like Lofty @ #28, I not much bothered about the big house or the foreign travel, and I don’t even own a car. By the standards of society I live a very modest lifestyle for someone of my age and professional position. On the other hand, by my own standards of, say, 20 years ago, I live a life of luxury and ease. I could certainly get by, and get by quite comfortably, on less than I do right now – it would just mean fewer meals in nice restaurants, fewer bottles of fine Scotch whisky, and fewer lengths of expensive shirting fabric going through my sewing machine. It’s all been thrown a bit into sharp relief right now, as my employer is struggling a bit because a big contract has stalled, and we were told on Friday that we need to cut costs. I’m already on reduced hours (I get by very nicely on what I make for a 30 hour week thanks), but I could probably stand to reduce them even further if I really needed to… Is my desire for a silk evening shirt and a ticket to the next Scotch Malt Whisky Society wine tasting dinner “within reason” if it means the difference between one of my colleagues losing their job or not? Or is the question obscene when the price of a shirt’s length of silk would feed a Syrian refugee family for a month? I don’t know…

John Morales@#21

and Caine@#24

Personally, I’m more with John Morales here. To begin with, I don’t even know what a “good person” is. I cannot agree with any of the definitions provided by our culture. Christianity inspired “humble, chaste, hardworking, charitable” seems plain stupid for me. I don’t like unjustified pride but, assuming you really have done something amazing, why not be proud about it? Sexual chastity is silly now that we have contraceptives. Why should I abstain from having lots of sex with lots of people if I enjoy it? Hardworking? Why bother? To further enrich the capitalist who hired you? Nah. To earn lots of cash and buy lots of stuff? But does it make you happy if you have no free time to actually do things you enjoy? I know that a 60 hour workweek wouldn’t make me happy no matter how much cash I earned. With being charitable it’s trickier. Sure, helping others is a good thing. But the logical conclusion would be to donate most of your income and to spend all your free time helping others. And ending up poor and overworked wouldn’t make me happy. Thus I perceive charity as good only within reasonable limits.

Then there’s also the capitalist version that a good person is “ambitious, hardworking, competitive consumer.” Obviously, I cannot agree with this either.

Sure, there are things I like in people (the obvious things, really). There are also things I don’t like in people (for example, stupidity, bigotry, rudeness, weakness, extreme greed, hurting other people, controlling other people against their will). But I cannot come up with a coherent definition of what the perfect person should be like. Our time is limited, so how much of their time the perfect person should devote to each “good” characteristic or action? Moreover, I definitely cannot define how the “perfect me” should look like. So I don’t even have a clear definition for what it is that I should strive for in order to become a “better person.”

I consider myself a hedonist; I don’t have any particular meaning or purpose for my life. This is why my goals in life are (1) to enjoy myself, have as much pleasure as possible while I’m alive, (2) don’t make the world worse, I don’t want to leave a trail of trash and pain behind me. Making the world a better place requires work and effort, which would interfere with my pleasurable lifestyle (generally I don’t enjoy working), so I settle for not making things worse.

The kind of person I want to be is derived from my goal of hedonism—I don’t want to dislike myself, I don’t want to hate myself. After all, hating yourself makes life significantly less enjoyable. Thus I don’t want to perceive myself as a very bad person and I have to do at least some of the things I like in people. As of now, I am happy with the way I am. I don’t have any reasons to hate myself, so I’m fine, it’s good enough.

Nowadays, whenever I do things that I like in people, it’s not because of a conscious desire to become a better person, it’s because I actually enjoy those things. For example, one of the things I like in people is being well educated. And it just so happens that I enjoy learning new knowledge or new skills, I also enjoy improving my existing skills. Learning things is fun, interesting, enjoyable. The end result is that I’m a hedonist who spends most of my time reading books and trying to improve my artworks. I’m very far from the stereotypical hedonist who is supposed to care for alcohol and drugs.

It seems to me that the reason this sort of ruinous acquisitiveness is common in capitalistic societies is a combination of systemic expectations and a class system that works to stifle human empathy rather than foster it.

The whole business of business is to shuffle real world input and outputs around until you maximise the difference and achieve the biggest profit you can. Those are the rules of the game as it is played in capitalist societies – often the legal rules as well as the systemic rules. CEOs of publicly traded companies have legal obligations to produce ever greater dividends for their shareholders, and can be replaced if they don’t turn their every effort towards doing so. Even if they weren’t compelled by law to conduct themselves in this way, the system is structured such that doing so is the very point of their activities. The human cost of maximising profits is seen as external to the game of capitalism, in the same way the wear and tear on the enamel on the chessboard is seen as external to the game of chess. Chess players don’t avoid moving their rook to A3 because it might scratch the peeling enamel on A3, after all. It’s not a concern in the calculations that matter for the activity at hand.

But a concern for those they are shafting can intrude on the rules of the game if the players have sufficient empathy. If their human emotions allow them to see the game for what it is – an arbitrary and invented system that has less than total compulsive force. This is why the class system is so pernicious, psychologically – it divides people up and stops them thinking of those in the other class (the lower class, the less important class, the expendable class) as full human beings. Marx begins by comparing capitalism to previous class-based economic structures – slavery and feudalism – and he does so not only to emphasise what is different about capitalism, but what is still the same. Marx was writing from the first generation to grow up after the French Revolution, from the generation to revolt in 1848, and one of his big concerns is to point out that, actually, the whole class-based structure of the ancien regime that Europe thought it had destroyed was still alive and well – except instead of free men and slaves as you have in slave economies, or lords and serfs as it was under feudalism, now it’s employers and employees. Yes, technically an employee can make enough money to start a business and become an employer – joining the capitalist class – but in practice it happens rarely because the employer class doesn’t think of the employee class as potential members of their own class, but as a resource to exploit. Technically a serf in a feudal economy could be ennobled and given lands and serfs of his own, or a slave in a slave economy freed and go on to own his own slaves, but it didn’t happen for much the same reasons. Lords controlled access to the social prestige needed to enter their class, freemen controlled access to the legal status needed to enter their class, capitalists control access to the wealth needed to enter theirs.

That’s why it is so important to think in terms of class, rather than just in terms of wealth and power. The kind of mainstream Neoclassical economics that is the non-Marxian orthodoxy doesn’t recognise class as a valid analytical tool, which is why it struggles to explain a lot of what happens in capitalistic societies (which is why Marx found it inadequate for his needs as an historian).

It is true that those who have been poor or even just reatively poor in their youth and early adulthood often retain a fear of poverty all of their lives, regardless of how much money they have. My parents were brought up in the 20s and 30s, both as the children of Methodist ministers so the bottom end of the middle classes with a lot of exposure to people far worse off than themselves. Their early adulthood took place during WWII, so again a period of considerable hardship for them and most of the population. My father was a mathematical genius who ended up with a chair at Oxford so they improved their economic lot significantly, but I recall him telling me that even though his pension was £33,000 (in the early 90s) and the house was paid off he feared destitution, he knew intellectually that this was extremely unlikely, but it was still a very real fear for him. Nevertheless, throughout their lives my parents gave to charity, were Samaritans (the suicide help line not the race) and gave all sorts of direct support to people not born as lucky as them. Part of that was due to their upbringing and faith, but I don’t think it was only that, I think it was a mind-set that seeing need in others fulfilled it if they could. I think that is the basic difference between people like them, of whom there are millions and people that accumulate wealth the way the mega rich do. I am not convinced that it is in any way a mental illness, I do think it’s a spectrum both of desire/need for wealth and of empathy/lack of empathy, to be a Geoff Bezos etc you need both an extreme need for wealth and an extreme lack of empathy for the vast majority of other people.

Marcus,

I think you are going about this the wrong way. You are looking for a preexisting ‘scientific’ label, already invented, listed, psychologist approved, etc. It would appear that this ‘syndrome’ or ‘condition’ does not have a proper label, even tho this condition has been properly described for centuries or millenia. I’ll grant you that we don’t have the cause of the condition quite worked out yet – but what is needed now is a proper label, we can work out the rest later.

I suggest that we just invent one. Make it sound scientific, but easy to pronounce. Pay particular attention to how it looks when abbreviated. Then spread it everywhere and hope it catches on. Get some grad students to write dissertations. Try to convince psychologists it should be a listed disorder.

I guess I sound a little jokey, but I’m not really. It’s a serious problem, the rich and those trying to be rich are fucking up the whole planet. It seems that humans need the proper (magic?) words to get anything done so let’s get on it!

Name that disorder!

Autarchomania?

I do not think this is a disorder, since it seems to be a perfectly standard mindset. I also do not think it has anything to do with growing up poor. It is a cultural thing more profound in USA than in Europe but strong here nevertheless.

A friend once told me in a jest that he knows nobody who says “I make enough money”, and I answered him seriously “yes you do – me”. He did ot want to believe me.

I grew up in a poor family and worked myself up to a comfortable middle-class position. A few years ago I befuddled many of my colleagues when I reclined to investigate an attractive job offer on the sole grounds that I would have less free time despite shorter work week overall, due to slightly longer travel and five vacation days per year less. That was all I looked at – the change in free time I would have. They did not understand why I do not try and find out if this were compensated with higher pay, which I actually had a decent chance at getting, since I was being headhunted and not doing the hunting.

Nobody could get their head around the idea that I do not actually need or want more money, that I am content with my income. Higher income would be totaly useless to me if I do not get to spend it on things that are fun – and for that I need free time. For example what use would be a super-modern belt grinder to me if it only stood on the working bench collecting dust? I cannot afford a super-modern belt grinder now, but I can use my time to build a cheap one that actually gets used and I can have fun doing so.

Growing up poor made me careful with my spending, but it did not make me want to amass riches.

Charly@#35:

I do not think this is a disorder, since it seems to be a perfectly standard mindset. I also do not think it has anything to do with growing up poor. It is a cultural thing more profound in USA than in Europe but strong here nevertheless.

That was sort of the point of raising the topic the way I did. It’s certainly “normal” behavior, in that it’s socially rewarded (even lauded) and is considered appropriate. Even though it may be damaging to society, it’s something we are taught is righteous.

Nobody could get their head around the idea that I do not actually need or want more money, that I am content with my income. Higher income would be totaly useless to me if I do not get to spend it on things that are fun – and for that I need free time. For example what use would be a super-modern belt grinder to me if it only stood on the working bench collecting dust?

I am pretty sure Lao Tze said something very wise-sounding about that.

Seriously, though, wealth is wanting what you have – not having what you want and being consumed with endless wanting. But that attitude has no value to the powers that be, so the would teach you otherwise.

@ Marcus, I am not familiar with Lao Tze, but if my memory serves correctly Seneca once wrote somewhere that being poor does not mean to have little, but to want to have more than you do.

As I recall from one version of the Tao Teh Ching:

“He is rich who knows how much is enough.”

:)

Bill Spight, I’m much rather have enough and not know it than know how much is enough and not have it.

(Perhaps I lack ancient wisdom)

There is an extant word, though it’s more about its effects: affluenza.

I found it:

It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor.

It does not name the source and I cannot find it anywhere, but I think I read it originally in Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium (Czech translation, I do not read latin above what knowledge of basic biological nomenclature allows).

Charly, #41,

It is indeed from Seneca the Younger’s Letters to Lucillius. The second letter, in fact, on good reading habits for one of a philosophical mind. In Latin the sentiment is “non qui parum habet, sed qui plus cupit, pauper est”. However, it is not a sentiment original to Seneca, as Seneca himself points out, but rather one he has taken from Epicurus (the original text of Epicurus does not survive, we know this fragment from Seneca’s quotation only, and then in Latin, not Epicurus’s original Greek). Seneca notes that this is a somewhat cheeky thing for a Stoic like himself to do, since the Epicureans were traditionally seen to be the great rivals and enemies of the Stoics as far as philosophy goes. He likens it to wandering into the enemy’s camp, for reconnaissance purposes, not as a deserter.

But the Stoics and the Epicureans were on pretty much the same page when it comes to the superfluity or active harmfulness of wealth. Indeed, in a later letter (letter 17), Seneca warns Lucillus that he should not put off studying philosophy until he has amassed enough wealth to keep himself in case the desire to amass ruins his carefully cultivated philosophical mindset, and prevents him from adopting the frugal mindset proper to one living in accordance with a truly virtuous human nature (the ultimate goal of the Stoic sage). Seneca points out that whether someone can cope with the burdens of wealth is not knowable before they are tested – people often wonder whether a rich man could cope with sudden poverty, but seldom ask whether the poor man might despise a sudden fall into riches. To the Epicureans, whose chief goal was the achievement of happiness by minimising want, the acquisitive urge was dangerous in itself. To the Stoics it was a distraction from what was important – pursuit of virtue in accordance with nature.

This particular piece of ancient wisdom is pretty common. This idea has popped up all over the world in different cultures at different times. Such attitude seems reasonable for me if you are reasonably well off. You aren’t starving, you have a comfortable home and access to healthcare? Great, consider yourself lucky; your life is nice and you might as well enjoy it. Stressing over amassing more wealth isn’t going to make you happier.

But, historically, there have been countless cases where somebody rich attempted to preach this kind of attitude to the starving and poor. For example, there was this one 19th century Latvian poet who was reasonably well off. He wasn’t very rich, but relatively better off than those peasants for whom he wrote poetry. And his poems were ridiculously didactic—be happy with what you have, don’t be greedy, don’t envy the rich, accept your lot in life, pray God, pay your taxes, don’t rebel against the rich. The cynic in me tends to suspect that sometimes teaching like “it is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor” were there only to make it easier for the rich to keep in check the impoverished. By the way, I don’t fully agree with this statement. Sure, wealth and perception thereof is relative, but, if somebody is malnourished and sick and cannot afford to buy food and medicine, then this person is objectively poor.

For the overworked American who frantically desires the newest iPhone model, minimizing want really could be a great way how to increase happiness. But, in general, I don’t buy this particular ancient wisdom either—not wanting anything isn’t happiness, it’s just apathy.

@Ieva #43 there is nothing in your comment I can disagree with.