One of the podcasts I listen to is the Intelligence2,[i2] which is generally OK, though sometimes horrible. The one I listened to most recently was pretty horrible.

It’s Sam Harris on the Science of Good and Evil [soundcloud] and – even if we credit Harris with having been jet-lagged and a bit scatter-shot, it’s pretty bad. Unfortunately, the introduction sets him up to face-plant, and face-plant he does – the introducer says: (@1:43)

“Sam Harris’ book – I’m just leaving aside the God question for a moment – is revolutionary in the philosophical sense in that it’s a great repudiation of David Hume and his idea that you can make statements of fact on the one side, and you can make statements of value on the other but there’s no correspondance between them.”

I couldn’t manage to get through Harris’ book in which he repudiates Hume (if he does) but that’s a brutal set-up. He appears to be referencing Hume’s famous is/ought argument, which was not exactly a division of statements of fact and statements of value as much as it was a dismissal of ideologues and moralists: Hume observes that it’s very easy for one to observe how things are, and then to say how one thinks they should be – but it’s difficult to make the argument as to why they should be that way, and he further observes a great deal of philosophical hand-waving and bloviation attempting to do so. In concrete terms: suppose someone parks a pickup truck on my toe. I can argue “your pickup truck is on my toe and you should move it promptly” and, while we can easily observe that the first part (there is a pickup truck on my toe) is true, the latter part (you should move it promptly) is merely a matter of my opinion.

The introducer’s characterization of Hume as being about discerning facts from values was actually a softball to Harris, because Harris is (or was) fond of talking about “moral facts.” The “moral facts” thing was interesting, while it lasted – Richard Carrier was also fond of pushing forward his own version of Harris’ argument – but here’s where I start to have a problem with what Harris is saying: immediately (@4:17)

“In the Q&A afterwards, if any of you feel that you have the knockdown argument against what I’ve said tonight, please don’t leave the room just muttering it to yourself – get to the mic and let me hear it, because I really don’t want to be wrong any longer than I need to be.”

Here’s the problem: Harris made a big deal out of his “Moral Landscape challenge” [harr] in which he says:

Many seem to have judged from the resulting cacophony that the book’s central thesis was easily refuted. However, I have yet to encounter a substantial criticism that I feel was not adequately answered in the book itself (and in subsequent talks)

I’m still shocked right out of my chair whenever I read that, because Harris is basically saying that there has never been a substantive critique of the warmed-over hot dish of virtue ethics and consequentialism that he’s been serving. “Yet to encounter a substantial criticism”? Well, Nietzsche was poetic and bombastic about it, and Hume was sly and witty, but both of those philosophers offered solid (if not outright devastating) critiques of ethical systems in general, which Harris has not overcome. It reminds me of watching a William Lane Craig debate, in which his opponent says, “please don’t use that old Kalam argument, it’s been refuted 10,000 times” and Craig replies, “Of course not! But: nothing exists without having a beginning, amirite?” Harris started putting forward his moral landscape argument 6+ years ago and it’s been not quite as thoroughly debunked as Kalam, but Harris’ method for dealing with those criticisms appears to be to dismiss them and continue on as though nothing had happened, as he does in the podcast.

It’s the only thing I can’t stand about Harris’ arguments, which is saying something because that seems to be a general trend in how Harris likes to argue:

Harris: Stuff

Other philosopher: Did you consider this, and that?

Harris: You didn’t understand me. I said: Stuff

Other philosopher: I think I understood you, which is why I asked you this thing and that thing.

Harris: Yeah, but I said Stuff.

Other philosopher: (clutches temples and screams)

Harris: See, there have been no substantive criticisms of my Stuff

It’s the same technique Harris deployed so irritatingly badly in his foray into physical/airport security and profiling. Bruce Schneier gently handed him his ass [sch], and Harris kept saying, “Yeah, but… (the same thing he had said before)” One cannot simply repeat one’s arguments, ignoring counter-arguments, and declare oneself un-refuted. I mean, William Lane Craig does, but that’s why we don’t respect his intellectual honesty.

Harris’ argument is that morality can be reasoned about because there are moral truths: things that we can objectively determine regarding peoples’ experiences in the real world, e.g.: suffering. (@7:37)

The moment you recognize that right and wrong relate to questions of human flourishing it becomes obvious that forcing half the population to live in cloth bags or beating them or killing them when they try to get out is not a good strategy for maximizing human flourishing.

A mere 6 minutes after all that grand talk about refuting Hume, Harris has driven a dirtbike down a ramp and slammed wheel-first into the opposite side of Hume’s chasm. Worse, it’s accompanied with a sad bit of well-poisoning: “it becomes obvious.” To whom, exactly, does it become obvious? I can’t say this as well as Nietzsche (few could!) but it’s not obvious at all: the people who are making women live in cloth bags and beating them wouldn’t be doing it if they didn’t think it was somehow maximizing their human flourishing. You can’t simply accept that it’s a bad idea, when – rather obviously – lots of people are doing it. One can (as Harris does) argue that it’s not a good strategy for the women in question, but if the men didn’t think it was a good strategy, they wouldn’t be doing it, would they?

Harris and Carrier and many others derive their argument from the work of Philippa Foot (who is more readable than either of them) and her book Natural Goodness. [amazon] I can’t find my copy but I recall Foot saying that she felt she didn’t have a good answer to her characterization of Nietzschean nihilism – which, if I understood her correctly – was a rejection of all morality. Unfortunately, virtue ethics depend on a presupposition of morals; they’re just called “virtues” – it’s a rather obvious reification of one’s extant ideas of right and wrong. For example, the virtue ethicist would say “we value being truthful because otherwise we cannot have justice, and justice is a virtue.” That’s an obviously circular argument. As Sextus Empiricus pointed out, when he refuted Sam Harris’ Moral Landscape in 210AD: “it’s circular arguments all the way down.” These are unadorned bog-stock critiques of consequentialism, in general, as well: you cannot say you’re building an ethical system out of “what’s best for people” without defining “best.” You can call it “maximizing human flourishing” or you can just say “good” or “right.” Foote and Harris argue that “human flourishing” is equal to “right” and therefore there is such a thing as “right” (and its contrapositive, wrong) but they beg the question of what “human flourishing” is. Nietzsche’s response would be: “you have no fucking idea.” Except that, as always, he’d say it better. Arguing against Nietzsche, though, is a cheat: like Harris, he was prone to unsupported assertions. Hume’s harder. If arguing against Nietzsche is like fencing with a master, arguing against Hume is like fencing with a ferroconcrete wall: Hume doesn’t leave you openings.

The person the virtue ethicists really ought to be arguing against is the Taliban, who – rather clearly – sees no harm whatsoever in making half the population live in a cloth bag or beating them if they try to get out. In fact, the Taliban see that as a virtuous and honorable behavior. Harris does not. Who’s right? There can be only one. Harris’ argument against the Taliban is that they’re wrong because I suppose it’s “obvious” to Harris. (@8:20)

“Let’s say we found a culture that was ritually blinding every third child – literally removing the eyeballs of children. Would you then agree that we’ve found a culture that was not perfectly maximizing human well-being? And she said ‘it would depend on why they were doing it.’ So, after my eyebrows returned from the back of my head, I told her ‘let’s say they’re doing it for religious reasons – say they have a scripture that says every third should walk in darkness or some such nonsense. And she said ‘then you could never say that they were wrong.'”

Worship a god that really hates you.

I find a lot of things distasteful about how Harris argues this point. First off, he doesn’t actually argue the point: he throws value-laden terms and concepts into his example, in order to try to come up with something that would shock even a nihilist. “Removing the eyeballs of children”, “some such nonsense” – these are rhetorical well-poisoning moves that can’t substitute for an argument. What Harris stubbornly refuses to do is explain why ritually blinding every third child is wrong. As Harris’ strawman interlocutor does not say, “What if you are talking to a worshipper of Sithrak?” Simply put, Harris is presuming that the Sithrak worshippers are wrong, which sure makes it easy to argue that they are wrong.

Back when Harris’ book came out, there was a brief spate of people arguing about “moral facts” and, of course, there was Harris’ big “prove me wrong!” challenge. At the time I offered a rebuttal that looked like this:

You appear to be reifying your opinions as “virtues.” It is a fact that people have opinions about morals, but opinions can differ. Your mission, if you’re creating a system of ethics, is for it to resolve differences of opinion about what people believe they should do. Your system doesn’t do anything like that. Furthermore, it’s not my job to prove you’re wrong, it’s your job to prove you’re right and I remain unconvinced.

Is the best that Harris has to offer a stacked deck full of emotionally-freighted hypotheticals? It seems, to me, that he invoked the example of the Taliban and failed to show how we can tell that it is a fact that the Taliban are wrong (or evil) (or even misguided) so he has to click over to an even sillier example. He ought to ask the Taliban, because they are a walking, talking, living example of how unfounded virtue ethics and consequentialism can be. That’s without even invoking the nihilist who says, “I don’t care if you think it’s wrong. I think it’s right for me and you can kiss my Converse.” That’s the fight that Foot ran away from: how do you convince someone whose virtues are what you consider vices? You don’t get to cheat and tell them “obviously, your idea of human flourishing is wrong” because obviously it’s not obvious.

Harris is oblivious to the obvious: (@8:44) He goes on to characterize his interlocutor:

“I was talking to a woman, which makes it even more shocking to me, actually, a woman with a deep background in science and philosophy. She has since been appointed to The President’s council for Bioethics in the United States – she’s one of 13 people advising President Obama on all the ethical implications in medicine, science and related technology. And she had just delivered a perfectly lucid lecture on the ethical implications of progress in neuroscience. She was especially concerned that we could be using FMRI-based lie detection on captured terrorists and she viewed this as a really unconscionable violation of their cognitive liberty. So, on one hand, her moral scruples were so finely tuned as to recoil from the slightest perceived misstep in our war on terror, and yet she was quite willing to forgive any culture that would remove the eyeballs of children in its religious rituals.”

Again, Harris casts his comment using value-laden language. What he doesn’t seem to understand is that the very examples he is giving are counter-arguments to his position that there are moral truths and that there can be a moral science in which we can argue about what constitutes a good strategy for human flourishing. Clearly, he and his interlocutor had very different opinions about this matter, which he chose to use as an example. Harris is trying to demonstrate that his interlocutor was wrong, by illustrating that he’s wrong about virtue ethics. It also illustrates what’s wrong with consequentialism: you’d expect that if it was possible to reason about the common good, Harris would have won his argument handily instead of bouncing off and having to demonize his interlocutor’s argument using value-laden language. Why didn’t he just whip out a pencil and paper and write down the relevant moral facts, then do some consequentialist extrapolation to calculate the greatest common good, and win the argument?

“I see this double standard as a problem. And, strangely, this is precisely the sort of failure of common sense and basic moral wisdom that nonreligious people worry about.”

Oh, Sam! “Failure of common sense and basic moral wisdom” because she didn’t agree with you? The failure, in that example, is the failure to find common moral facts, to build an ethical system out of them that allows resolution of disagreeing opinions to determine what is the best outcome for human flourishing.

I sometimes encounter people who make value-laden hypotheticals to try to advance their opinion, as Harris does. Short form: “but what about the children?” My response is usually, “I hate children.”

I’m not going to wander through the entire hour-plus on a point-by-point basis, because my cringing muscles are starting to cramp up. I’ve actually listened to it several times, mostly because I’m listening for the moment where he refutes Hume. Instead, he demonstrates over and over again exactly what Hume was talking about when he wrote: [wikipedia]

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning, and establishes the being of a God, or makes observations concerning human affairs; when of a sudden I am surprised to find, that instead of the usual copulations of propositions, is, and is not, I meet with no proposition that is not connected with an ought, or an ought not. This change is imperceptible; but is, however, of the last consequence. For as this ought, or ought not, expresses some new relation or affirmation, ’tis necessary that it should be observed and explained; and at the same time that a reason should be given, for what seems altogether inconceivable, how this new relation can be a deduction from others, which are entirely different from it. But as authors do not commonly use this precaution, I shall presume to recommend it to the readers; and am persuaded, that this small attention would subvert all the vulgar systems of morality, and let us see, that the distinction of vice and virtue is not founded merely on the relations of objects, nor is perceived by reason.

That is, in fact, exactly what Harris is doing when he says:

The moment you recognize that right and wrong relate to questions of human flourishing it becomes obvious that forcing half the population to live in cloth bags or beating them or killing them when they try to get out is not a good strategy for maximizing human flourishing.

Key word: “obvious” secondary key words: “not a good strategy for maximizing human flourishing.” See: begging the question [wikipedia]

Toward the end, there are several softballs lobbed at Harris, which he dodges (not a good strategy for optimizing human flourishing with regard to softballs) (@1:11)

The MC asks Harris (paraphrasing) If your intention is to achieve well-being, taking the example of capital punishment and given arguments both for and against, are we then going to get a utilitarian scientist to come along and adjudicate which one of these well-being competitors has the higher peak on the landscape? Harris replies:

“There is this Orwellian concern about guys in white lab coats coming forward as the morality police. I don’t understand it given how we feel about medicine. When medicine has some information to give us, like: ‘guys you really want to hear this – this thing is going to kill your children.’ We are desperate for the information! We are not standing back thinking ‘well, there’s something Orwellian about the uncompromising stance of medicine on this subject. If psychology came forward with a really robust and deep understanding of how to raise happier children what parent isn’t going to want to know it? That immediately intrudes on the space of morality…”

Somehow, Harris has decided to argue that anti-vaxxers obviously won’t happen, and that home-schooling parents won’t closet their kids so they grow up religiously indoctrinated. He throws out two things, back to back, that happen all the time, while saying that they don’t happen. I didn’t bother to dig up video of this session, but I can imagine a reaction-shot of the interviewer:

Then, realizing that he missed the question, he careens off in a different direction. Remember, this is Harris’ response to what ought to be a softball question:

“I just realized that I forgot to answer the core of your very interesting question – what do we make of the fact that there are certain contexts in which barbaric actions may be necessary for survival or viewed, in fact, as morally good: it’s something I do actually discuss in my book; if you imagine the landscape could be such that you might have to descend in order to reach a higher place.”

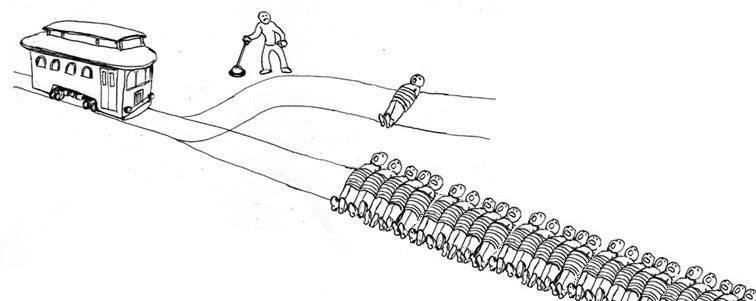

I have heard better and clearer arguments from Deepak Chopra. To be fair, Chopra has Quantum. In the closing Q&A Harris throws himself in front of the Trolleycar Problem, which is a horrific strategic blunder: if consequentialism were practical, wouldn’t we be able to compute the correct response to the Tolleycar Problem? If virtue ethics gave practical answers, wouldn’t we know immediately which action the virtuous person would take? Yet Harris, who is arguing for a form of consequentialism, derides consequentialism as “usually being framed in terms of body-count.”

It’s a bizzare performance.

One of the questioners (who was obviously prepared) asked Harris the big question: (@46:15)

“What is the scientifically demonstrable fact that tells me I ought to value human well-being?”

Harris’ answer:

“That is a – … In articulating that concern, as I tried to show in my opening, you have put the bar at a level that no other branch of science can clear. So, if you think that a science of morality must meet an epistemological test that physics, chemistry, and medicine can’t meet, then that’s a double standard that’s intellectually unjustified and unsustainable. And I see no reason to do that. In fact, I think the value of avoiding the worst possible misery for everyone, which is – again – the only assumption I need you to grant for me to have this space of possible experience open up, is more fundamental than the value of understanding the universe, the value of being logical. If you’re going to give me a choice between knowing a certain fact in physics and plunging into the worst possible misery for everyone, I’m going to say ‘well, yeah, there are certain physical facts it’s rational to not want to know. So while I can’t give you a scientific reason to want to avoid the worst possible misery for everyone, once you grant the reasonableness of that – which, again, I think is even more reasonable than reason itself, then scientific understanding of human consciousness would give you subsidiary values. We could ask the question ‘well, how important is compassion?’ ‘How can we best teach children to be compassionate?’ That’s a question about cognitive neuroscience. That is: the more you know about the brain basis to compassion, and the genes that underwrite it and the cultural institutions that manufacture it – then you’re talking a game of scientific detail – again, telling you if it’s a trade-off between compassion and bureaucratic efficiency how do we balance those two things? Well, there is a right answer – it’s fantastically complex – but there has to be a right answer, or a number of right answers and many many wrong answers.”

The refutation of Hume is somewhere in there. I’m sure of it. Under the arugula.

Harris makes a move that strikes me as leading with his chin: he claims that it’s reasonable to ignore other philosophers’ work because the consequence is endless argument: (@35:22)

That’s been controversial among philosophers. There are two reasons: one, I genuinely think that many of these concepts and threads that we’ve had to follow over the centuries in the discussion of morality – I think they’re confused and they generate unnecessary confusion. To break – to start every discussion about moral truth with a discussion of consequentialism on one hand, and deontology on the other and Aristotle’s virtue ethics on another, and you have to talk about Kant and … One: it’s deadly boring to most people and two, I think it’s actually confusing. When you look, as normally presented, it seems there’s a stalemate between consequentialism and deontology. I don’t think there is – I think the deontologists are covert consequentialists even when they say they’re not. The only reason why Kant’s categorical imperative were to make any sense at all is because it has good consequences, and if it had reliably bad consequences it would not count as an ethical mass(?)

[the MC interjects: “But not getting involved in that fight with the philosophers…”]

I have, subsequently, to nobody’s pleasure.

[MC: “… ducking the fight with the big boys and girls.”]

Well, not at all. Subsequently certainly not. I’m aware of the literature – you know, I have a background in philosophy and to the consternation of many philosophers, I actually consider myself a philosopher. My PhD is in neuroscience by my interest in neuroscience has always been philosophical. I’m interested in the way in which our scientific understanding of the brain…”

I’m sure Deepak Chopra considers himself to be up on quantum mechanics, too.

This is a problem I’ve wrestled with for years, to be fair to Sam. Philosophy encompasses a huge body of knowledge, and when you start digging into it, you’ll often find that someone has held your position (or refuted it) many times or centuries before. So, you modify your position, or you look at the classical critiques of that position, and then you find (as so many of us do) that you’ve become a historian of philosophy and not so much of a breaker of new ground. Put differently: you are a footnote to Plato, so you’ve got to get used to that.

The problem is basically epistemological: you can’t just jump straight into physics and start innovating in quantum mechanics, without all the background – and you can’t just jump straight into philosophy and declare that all those Kant and Aristotle and whatnot are “deadly boring” and “confusing.” What Harris is saying is that he’s easily confused and he’s prone to boredom and he wants to be like a high school math student who guesses approximately what the answer ought to be, but is ignorant; that’s why the teacher insists: “show your work.” It’s an efficiency thing: when someone says “blah blah blah and I overcome Epicurus’ challenge to religion thus: blah blah blah” it saves the interlocutor time because then they know they don’t have to ask you Epicurus’ perfectly obvious question – it’s not “deadly boring” it is the very terrain itself of the battlefield of ideas.

Demonstrating a familiarity with the philosophic classics is the entry cost: you’re not allowed on the battlefield at all unless you’ve got a shield that can withstand Nietzsche, and a sword that’s been sharpened by David Hume, and if you forgot your +5 Voltaire Armor of Sarcasm you’re fucked and you’re a fucking idiot to walk onto the battlefield at all. That’s basically what I think Harris is doing: he’s marched out there and is getting philoso-ganked by people who are not ignorant, easily confused, and easily bored. But he’s saying “‘Tis but a scratch!” Harris is like the Black Knight, in other words.

‘Tis but a scratch!

After all, he’s still talking about his moral landscape stuff, just like William Lane Craig talks about Kalam, and the black knight keeps spitting threats, while the puzzled Arthur asks, “what are you going to do? Bleed on me?”

How do you listen to that drek? Do you need wine, beer and/or liquor?

Raucous Indignation@#1:

How do you listen to that drek? Do you need wine, beer and/or liquor?

I listen to podcasts while I’m out driving or walking or whatever. In this case I was mowing the lawn, and kept driving the mower into things while screaming “WUT!?! WUT!!!!”

I may have a Valium and a glass of red wine and some curry to help maximize my human well-being for the rest of the evening. That’s my moral calculus and I’m sticking to it – don’t ask me “show your work.”

Curry? That’s what I use too.

Marcus:

There’s a lot that is weak/confused about Harris’ arguments, and I won’t bother to defend any of it. I would propose that you should consider his ethics separately from his metaethics, but there’s little point to considering Harris in particular to begin with, since so many others have given much better defenses of moral realism.

Hume would have had some criticism for Harris, no doubt about it, although it’s not at all obvious what Harris needs to “refute” from Hume to maintain his position But frankly, I think you should be honest and note that he would not have given you the time of day (from the Enquiry, with my emphasis):

Maybe it’s good advice, if a little harsh, but let it be on the record that I’m trying to work with you here anyway, because you seem like a pretty cool dude who’s generally quite reasonable and honest (at least in other contexts).

If I’m reading your position correctly (although it is hard for me to figure out), Hume should certainly not be treated like your sock puppet, as he does not endorse anything like your position. In his Treatise and his Enquiry, he develops a sort of psychological theory, which is of course quite dated and remarkably lacking in empirical input. At times, there is little more than Hume’s own personal introspection, to guide the conclusions he’s made from his armchair — fairly ironic, for somebody who is supposed to be considered the arch empiricist and naturalist (even if he was much more of one, relative to his contemporaries). You can take that irony as a good sign or as a bad one, but it makes no difference to me, use it as you will.

To dive straight into the main point here, Hume did not take it, as arguably one of the least superstitious people on the planet, that there are no facts about the “sentiments” or “passions” which guide our moral thinking. Those are features of the natural world, like any other, and they should be treated as such. There’s no question about how he’s thinking of these things. But you have to try to put yourself in that time/place and understand that the philosophical camp most strongly opposing his is the Rationalistic method dominant in ancient/medieval times (tracing back to Aristotle and Plato), whereby one may “derive,” with mere logic or calculations, a result about nature. What is there in the real world? How does that stuff work? You can’t get those answers only by thinking hard, and of course that’s not a recommendation to dispense with rationality or to stop thinking clearly. This is a much more general concern for Hume, which feeds into how he’s going to address the topic of morality (and tons of other stuff) when he finally gets around to it.

Here’s the sort of thing he thinks you get with clear thinking, coupled with experience…. All sorts of modal claims, particularly ideas involving causation and so forth, simply aren’t features which are available strictly with sensory/perceptual data. You don’t see “causation,” as he famously argued, only A then B, A then B, A then B. So, the basic project appears to be to understand how our ideas come about — that is especially important when they do have any legitimacy in our thinking, like causation does, because we need to keep those ideas and use them properly. It is not to reject them outright, as some kind of illusion or fallacy or epiphenomenon, because they do not have the form which you presupposed they need, in order to satisfy whatever naive pre-theoretical notions that you may have had about the subject. So, with that frame of mind, you (Hume) put together a quasi-psychological theory, according to which we have pains, pleasures, etc., that these are factors working behind the scenes in our brains, which underlie much of our ordinary reasoning (moral or scientific or otherwise).

Without having to reason about it, you immediately sense that certain things are pleasurable to you and others are not; and very importantly, you’re capable of recognizing the same types of experiences in others and can reason about them in much the same way. That’s the real factual thing that happens in the world, which is an essential part of what you’re bringing to the table, whenever you’re going to try to discuss that topic coherently. You do the latter (empathize and sympathize about others’ sentiments and passions), despite being incapable of proving/deducing logically that other such minds exist or even that there is any external world whatsoever.

He sees fairly clearly that radical skepticism of that sort simply cannot be defeated with any such argument. All the same, there is no need to do anything like that, which means it isn’t a genuine problem, which means (without it) we still seem to have all of the tools that we need to do the real work of moral philosophy (etc.). As an empiricist he starts in a place very close to Berkeley’s, then he declines to follow this idealistic “logic” where it is supposed to take us — he doesn’t think we need to become solipsists or radical skeptics of of that sort, when we actually get out of our philosophical armchairs and seriously do the real business of the world (like for example reasoning about moral/political situations).

He does take all of it quite seriously, and what he’s doing instead is trying to express one way how it could be understood with a naturalistic worldview like his. If you read him carefully (or even not so carefully), it’s as if you could hear him saying slogans like “you can be good without god” under his breath, after a nice hearty laugh about foolish people who seem to think otherwise because they have some sophistical argument which appears to prove it impossible. That’s the kind of perspective you should have, at least according to this interpretation of Hume, certainly not that all is lost or that it could only have a full and satisfying explanation that depends on supernaturalism.

In every system of morality, which I have hitherto met with, I have always remarked, that the author proceeds for some time in the ordinary way of reasoning,

I find it ironic that Hume is using an inductive argument.

To the consternation of many neurosurgeons, I actually consider myself a neurosurgeon. OK, I don’t have any qualifications in neurosurgery, and my preferred tools are a blunt hatchet and a claw hammer, but still…

Well, there’s a novel and thought-provoking statement, which has surely never before been articulated by any student of philosophy! What a remarkably incisive and challenging thinker this Harris chap is!

Yeah, that’s exactly what I told the judge at the hearing about my “indecent exposure” charge, but he didn’t buy it… Oh, you didn’t mean pants? My mistake…

Dunc@#6:

To the consternation of many neurosurgeons, I actually consider myself a neurosurgeon.

Ha!

I think it’s interesting how we use qualifications as a sort of meta-label. Calling oneself a “philosopher” implies at least more than nodding familiarity with the classics, as calling oneself an “engineer” implies some familiarity with materials and design, or calling oneself a “neuroscientist” implies some knowledge of brain layout and function, etc. So when Harris says “I am am philosopher” he’s trying to cut around the problem I mentioned, which is that it’s suspicious to say “the classics are dead boring and confusing.” It’d be like a surgeon saying “sure, I know that anatomy’s a thing! now, I am going to remove this big lumpy thing over here!” Uh, that’s my elbow.

At the beginning of the recording, Harris says something about how he’s accused of hubris, or maybe it’s jet-lag – or maybe his hubris is so great he can’t tell he is hubristic. I think that was the most right thing he said in the entire recording, except his name.

Interesting how Harris always acts as though humans have no history whatsoever. If there’s one thing history clearly shows, no matter what part of the world, it’s that humans excel at deciding that ‘human flourishing’ is utterly dependent on killing those humans into oblivion, near oblivion, or enslaving them all.

‘Human flourishing’ is one damn stupid basis for anything, given how we naked apes act toward one another. We haven’t even sorted out the simple stuff yet.

consciousness razor@#4:

it’s not at all obvious what Harris needs to “refute” from Hume to maintain his position

I probably didn’t put enough of the context in my description, but: the only reason Hume entered into the discussion was because the guy who introduced Harris cast it as a repudiation of Hume. I’m not sure if they explicitly mentioned the is/ought problem, or if that was something I inferred; it’s pretty typically brought up as a hurdle when someone wades into the whole ethics/morals quagmire. But #notmyquagmire. I’m not a philosopher or a neuroscientist and I’m really hesitant to dip my toes into the topic because as far as I’m concerned it’s a bottomless pit of despair.

Hume:

Let a man’s insensibility be ever so great, he must often be touched with the images of Right and Wrong; and let his prejudices be ever so obstinate, he must observe, that others are susceptible of like impressions.

Yes, that seems to be the case. That’s why I’m careful to try to distinguish between opinions and facts – Hume here calls them “impressions.” I do think it’s undeniable that we have the sensation that there is a right/wrong, just as we have the sensation that there is a free will.

It’s somewhere around, that I lose traction and can’t get any further.

Maybe it’s good advice, if a little harsh, but let it be on the record that I’m trying to work with you here anyway, because you seem like a pretty cool dude who’s generally quite reasonable and honest (at least in other contexts).

Well, thank you. I try to be honest; some say it’s the best policy. I agree, but mostly because it’s the path of laziness.

So, for the record: I am comfortable with the things I am ignorant about and am always looking for ways to learn. I don’t have a particular ideological bent that I’m trying to fit the world into. In the case of ethics/morals (and free will, for that matter!) I’m genuinely trying to understand WTF. That’s why I read so much of this stuff – where my wheels start to spin is when I conclude that just surveying the landscape is several lifetimes’ of work. Or, it appears to be. If I had spent my time studying philosophy instead of programming computers and doing computer security stuff, I probably would understand that field as well as I do the security (which is to say: barely) I don’t mind being told I’m ignorant because I often am, and I don’t insist on being right all the time, like Sam Harris seems to.

Hume:

The only way, therefore, of converting an antagonist of this kind, is to leave him to himself. For, finding that nobody keeps up the controversy with him, it is probable he will, at last, of himself, from mere weariness, come over to the side of common sense and reason.

This reminds me of the recommended response of extreme skeptics – even though Sextus Empiricus may doubt his ability to know anything with certainty, it appears to him now that he’s hungry, so he eats anyway.

FWIW I feel the same way about free will. It doesn’t matter whether we have it or not because we’re so strongly programmed to interact with the world in ways that make us believe we do, that for all intents and purposes we do. It’s like arguing about whether we have 3D vision or not: well, not really, but we do – or most of us do. (I have a friend whose brain happens to not give him a 3D experience. We’ve had some really interesting conversations about how he learned to drive by training himself to estimate distance based on the apparent size of other cars… So, then the question is “does Peter G. have 3D vision?” Well, if you need 3D vision to drive, he does. I digress.)

If I’m reading your position correctly (although it is hard for me to figure out), Hume should certainly not be treated like your sock puppet, as he does not endorse anything like your position.

I am actually trying not to have a position. So, perhaps that’s why my position is unclear.

The introduction of Hume was by the fellow who MC’d the broadcast, although, by editorially selecting those remarks to comment on, I suppose I was also introducing Hume into the discussion.

My position is that the is/ought divide is the least of our problems, and when I try to think about this stuff, I get stuck at Pyrhhonian skepticism and wind up in a ditch with my wheels waving in the air.

In his Treatise and his Enquiry, he develops a sort of psychological theory, which is of course quite dated and remarkably lacking in empirical input. At times, there is little more than Hume’s own personal introspection, to guide the conclusions he’s made from his armchair — fairly ironic, for somebody who is supposed to be considered the arch empiricist and naturalist (even if he was much more of one, relative to his contemporaries). You can take that irony as a good sign or as a bad one, but it makes no difference to me, use it as you will.

I thought it was fascinating. In fact, Hume’s introspection on how we form impressions about other people’s emotions shapes a lot of my thinking about anger/being offended that I describe in my Argument Clinic on verbal abuse. More important, to me, was his method of introspection – it seems to me to be the only valid way of understanding our experiences because we’re the only people who experience them exactly the way we do. By introspection about our experiences we can then communicate with another person: “hey, when you experience anger, does it go sort of like this?” and then we may be able to share an approximate idea of that experience between us.

I read Hume in 1983 or 4. I suspect I’ve mentally drifted pretty far afield since then – I think most of us form a map of the points of someone’s arguments that strike us as particularly salient, then go back and basically quote-mine them forever afterward. Another possibility is that there are some parts of Hume that I understood, and a lot I didn’t, and I remember the parts I understood because that’s all I’ve got.

To dive straight into the main point here, Hume did not take it, as arguably one of the least superstitious people on the planet, that there are no facts about the “sentiments” or “passions” which guide our moral thinking. Those are features of the natural world, like any other, and they should be treated as such.

Yes. I probably use the word “opinions” where Hume might use “impressions” “sentiments” or “passions.”

And, I am not saying there are no facts about those. Now, I’m talking about my views, not Harris’ or Hume’s: it seems to me that it is a fact that we have impressions or opinions about what is right or wrong. I’m quite comfortable saying that. I’m quite comfortable saying that most people (AKA: The Vast Majority) have opinions about certain things, e.g.: “killing me is bad.” We can say that it’s a fact that most people don’t want to be killed. We can call that a moral fact, I suppose, but there’s a difference between:

– it’s a fact that most people don’t want to be killed

and

– it’s a fact that nobody wants to be killed

when, obviously, there are people who want to be killed. And, I think we can build moral systems on the basis of broadly held opinions, though we encounter problems when we encounter someone who does not share those opinions. That’s why I was critical of Harris’ response of demonizing his interlocutor as being “lucid” up until the point where she disagreed with him.

But you have to try to put yourself in that time/place and understand that the philosophical camp most strongly opposing his is the Rationalistic method dominant in ancient/medieval times (tracing back to Aristotle and Plato), whereby one may “derive,” with mere logic or calculations, a result about nature. What is there in the real world? How does that stuff work? You can’t get those answers only by thinking hard, and of course that’s not a recommendation to dispense with rationality or to stop thinking clearly.

Yes. I think that’s a good description of what’s going on.

Hume is navigating a much larger mine-field than Sam Harris and I are.

Without having to reason about it, you immediately sense that certain things are pleasurable to you and others are not; and very importantly, you’re capable of recognizing the same types of experiences in others and can reason about them in much the same way. That’s the real factual thing that happens in the world, which is an essential part of what you’re bringing to the table, whenever you’re going to try to discuss that topic coherently. You do the latter (empathize and sympathize about others’ sentiments and passions), despite being incapable of proving/deducing logically that other such minds exist or even that there is any external world whatsoever.

First off, let me thank you for taking the time to explain all this so well. It appears to me that, aside from substituting “opinion” for sentiments and passions. I’m probably creating confusion by using my own vocabulary (it’s how I think! damn it!) so I’ll see if I need to adjust that.

He sees fairly clearly that radical skepticism of that sort simply cannot be defeated with any such argument. All the same, there is no need to do anything like that, which means it isn’t a genuine problem, which means (without it) we still seem to have all of the tools that we need to do the real work of moral philosophy (etc.).

So, if I am following you correctly (I think I am) then that’s sort of where I wind up, too. I think the problem I have with Harris or strawman forms of consequentialism is that they appear to be claiming that we can rationally judge these things (opinions or sentiments/passions) and somehow determine what’s right from outside – when Harris talks about “going up” or “going down” on a “landscape” I feel like the implication is that we can somehow map all these opinions and sentiments and weigh them against eachother. I don’t see that happening – on the contrary I see Democracy as a way of doing some of that through brute force – screw it, let’s count noses and see who outnumbers whom and would probably win if it comes to a knife-fight (as a way of avoiding the knife-fight).

he doesn’t think we need to become solipsists or radical skeptics of of that sort, when we actually get out of our philosophical armchairs and seriously do the real business of the world (like for example reasoning about moral/political situations).

OK, so I did have that part wrong(ish) – I was remembering Hume as erecting a skeptical block and then walking away from it, as a way of undermining moral systems in general. If what Hume was doing was erecting the skeptical block as a way of saying “you’ve got to talk about this stuff” then I’ve been completely in agreement with that for a long time (and wrong about Hume for a long time, too – see my earlier observations on mis-remembering)

Caine@#8:

‘Human flourishing’ is one damn stupid basis for anything,

Well, I think it’s a reasonable goal – but Harris talks about it like it’s something quantifiable and achievable. I suppose that’s because otherwise we’re stuck saying “I guess we’ve got to muddle through and see what we can do. Ideally we’ll do the best we can in the situation we find ourselves in…” but that doesn’t have enough Quantum. It sounds uncertain and waffly.

Marcus:

I don’t. I don’t think it’s awful if humans flourish in the sense of doing well, having healthy societies and all that, but holy shit, we’re light years from that. Right now, we’re too busy bombing the hell out of one another, and other human flourishing activities.

My problem with positing that as a goal comes from not being completely white, and observing white, colonial attitudes toward everything. White people see everything as possessions to be used, then trashed. They don’t give a shit about anything other than ‘human flourishing’. They don’t care about all life. They don’t understand the connection; they don’t care about our planet, which allows for our life. And so on. I get so damn sick and tired of explaining this sort of thing, only to have certain self-styled philosophers dismiss me, because I’m pushing spirituality, and there’s no such thing, and so on. Discussing these issues really makes me want a lot of people kicked right off the fucking planet, they are such pretentious assholes who can’t see past their own nose, or how immersed they are in colonial mindset.

Caine@#11:

They don’t give a shit about anything other than ‘human flourishing’. They don’t care about all life.

Good point. “Human flourishing” would need to encompass “not fucking the planet up so badly it collapses civilization” – but that would require a deeper understanding of “human flourishing” (back to my earlier point regarding causality: I don’t think consequentialism works when you don’t understand the consequences of your actions, and are engaged in short-term thinking)

There’s more I could say, but figuring out what to write can be tricky.

Meanwhile, here’s a quibbles:

I am not sure I understand your invocation of Sithrak. As I recall, Sithrakists are quite up front that Sithrak will treat all people the same (including the Sithrakist proselytizers themselves) after they die: eternal torture, no matter what they did in life. So there’s no way to get to “blind every third child (or whatever) because Sithrak says so”, because the main tenet of Sithrakism is that Sithrak will not reward the ones who do such blinding with less torture, or punish those who fail to do so with more torture.

(Of course, Sithrakists might be wrong about Sithrak)

Marcus:

Okay, that’s basically where I get off the train, because that seems very misleading. I’m not opining that I regularly have back pains; that’s just one of the things I feel. Given the way most people would ordinarily use/interpret the word “opinion,” it would pointless for anyone else to form some kind of contrary opinion about my feeling of pain in my back (and neck, and various other places). Their “opinion” on this, if they even have one, counts for absolutely nothing because it can’t be based on any intelligible reasoning/evidence; however they’ve formed this opinion, they couldn’t have had access to the same relevant real-world information about my back pains that I do. Their senses, like mine, only cover their own pains, not those of other people.

Meanwhile, you might use the word in a somewhat different way, which is closer to the ordinary meaning. You might say a person has the opinion that Trump is the best president ever. I think that is also false. It’s just a plain old false claim about the world we live in. He isn’t, and what you see if you look into how this plays out, is that this type of “opinion” simply doesn’t stand up to the same degree of scrutiny as our shared opinion that he’s an awful president, which is based on a significant amount reason and evidence, rather than ignorance, tribalism, etc.

They’re not even close to being on an equal footing — that’s a perfectly reasonable sense in which we know the truth and they don’t. And it doesn’t do anybody any good to act as if this is merely a collection of contrasting opinions, because in a case like that, there are clearly plenty of genuine facts to know about (or not know about, as the case may be). Some people just don’t know the facts, but they can still form some kind of “view” (not so much “opinion”) even when they lack such information.

Alright, but Hume is more optimistic (for lack of a better word) than you seem to be. He’s not saying stuff like “as far as I’m concerned it’s a bottomless pit of despair.” That’s your (apparent) nihilism or anti-realism talking, and that isn’t his position.

Well, there is a distinction to be made about realism — leaving aside consequentialism for the moment. Here’s a realist claim: there is a territory that could (in principle) be mapped. It’s another question whether we humans are capable of doing the mapping.

If a few hundred years ago, you had asked whether people would be able to see the farside of the moon (in order to map it), you might have thought feats like that were beyond our abilities. Yet there is a farside out there in the world; that’s some territory in reality, which we just weren’t capable of mapping until recently.

Of course, there are conspiracy theorists who still maintain that people never went to the moon, so we may encounter that kind of denialism/skepticism, in addition to the sort that claims there can be no territory to speak of unless it’s actually already been mapped out. Both are ridiculous (in this moon example at least), and it’s important to be on the right side of either of these arguments.

Let me clarify a couple of things:

Sympathy is maybe a way in which we can feel something similar/related to what others feel, and I don’t mean to leave that out, since it is very important. But I don’t want to confuse it with directly experiencing a back pain or whatever.

As I said, we’ve got all of the tools we need, there isn’t a genuine and insurmountable problem, we can get by just fine, and so forth — no bottomless pits. It might not be that you really have a problem with realism at the end of the day (I’m sure that’s how you live out your life in practice anyway), but if you think you’ve got arguments directed against that, then it’s definitely one place where we disagree.

Owlmirror@#13:

There’s more I could say, but figuring out what to write can be tricky.

Oh, believe me, I sympathize.

I am not sure I understand your invocation of Sithrak.

I wasn’t trying to make a deep point, I just thought that I’d counterpose Harris’ hypothetical about the children’s eyes being gouged out. Also, I had another reason to invoke Sithrak: he’s on my mind right now for unrelated reasons.

Harris has a fondness for coming up with emotionally charged and often gruesome hypotheticals, gouged eyes, ticking time bombs, torture, that sort of thing. I understand why he’s doing it – it’s sort of the opposite of a reductio, applied to emotions: “if I can get you upset about this thing, you ought to be upset about this other thing.” It seems manipulative to me.

Of course, Sithrakists might be wrong about Sithrak

When I saw that, I switched my allegiance to GUJA, the God of Uncertain Jerking Around. His followers’ core tenets are that they don’t know their core tenets.

I always feel so ill-educated when I post early in one of your threads and then go back and read the rest of the comments. But then you go on about Sithrack, and all is well again.

Hume made me stop my deep dive in philosophy when I was a teen. I had a lot of problems with what people believed, why they believed them, and how they reasoned their beliefs — partly because I wondered about what I may have been missing, given that so many people believed things I thought were absurd, contradictory, or frankly, stupid.

I read a lot of philosophy and religion, and was frustrated that so little of it stayed on a line I found reasonable and reached conclusions I thought were justified.

Then I finally got around to Hume and said, “Oh, ok. There it is. These things have been said. I can get back to living a relatively normal life.”

consciousness razor@#14:

Okay, that’s basically where I get off the train, because that seems very misleading. I’m not opining that I regularly have back pains; that’s just one of the things I feel. Given the way most people would ordinarily use/interpret the word “opinion,” it would pointless for anyone else to form some kind of contrary opinion about my feeling of pain in my back (and neck, and various other places). Their “opinion” on this, if they even have one, counts for absolutely nothing because it can’t be based on any intelligible reasoning/evidence; however they’ve formed this opinion, they couldn’t have had access to the same relevant real-world information about my back pains that I do. Their senses, like mine, only cover their own pains, not those of other people.

You’re right! Now I will try to adjust my vocabulary.

You were kind enough not to point out that I was using the word in a form of well-poisoning, exactly as I complained about Harris doing. Thanks for not hammering me. Damn.

Alright, but Hume is more optimistic (for lack of a better word) than you seem to be. He’s not saying stuff like “as far as I’m concerned it’s a bottomless pit of despair.” That’s your (apparent) nihilism or anti-realism talking, and that isn’t his position.

True. I wasn’t trying to mis-characterize Hume.

When I say “it’s a bottomless pit of despair” I was editorializing. I like your way of explaining this:

Well, there is a distinction to be made about realism — leaving aside consequentialism for the moment. Here’s a realist claim: there is a territory that could (in principle) be mapped. It’s another question whether we humans are capable of doing the mapping.

That makes sense to me and it’s what prompted my “pit of despair” characterization – if we accept the claim that there is a territory that can be mapped, it doesn’t mean that we will do it or even that we ever will be able to, other than in principle. So, what’s all the hue and cry about? There are moral facts, but .. what? Aren’t we still going to be left arguing about their interpretation?

(I’m reminded of Dennet’s comment on free will – that, sure, we have free will but not such as we’d think is worth having. This seems to be another one of those situations.)

Sympathy is maybe a way in which we can feel something similar/related to what others feel, and I don’t mean to leave that out, since it is very important. But I don’t want to confuse it with directly experiencing a back pain or whatever.

Do you mean sympathy and not empathy? I see you describe it as feeling something similar/related, which I would call empathy (sympathy is more akin to pity). Otherwise, I agree with you. Putting ourselves in others’ place – is that not the underlying mechanism of “do not do unto others as you’d not have them do unto you”?

It might not be that you really have a problem with realism at the end of the day (I’m sure that’s how you live out your life in practice anyway), but if you think you’ve got arguments directed against that, then it’s definitely one place where we disagree.

I don’t have arguments against realism. I’m also not interested in preserving any particular position – my interest is in trying to understand what we’re all stuck with. I’ve described my views as “nihilism” based on typical definitions of moral nihilism but with a skeptical twist – more along the lines of “I remain unconvinced by any particular moral system” or perhaps even “I remain unconvinced of the usefulness of any particular moral system.” As I’ve described elsewhere, I believe we can individually establish our own rules that we’re comfortable with, and it appears to me that the majority of people (maybe a thin majority) do a job of it that I can’t complain about. I do, however, take as evidence of the non-practicality of ethical systems the observation that there are a whole lot of lying, cheating, murdering, raping, totalitarian assholes. They’re perhaps not an argument against realism, because one can say “perhaps they know what’s right and just choose to do something different” but I’ll take them as evidence that ethical systems have very little prescriptive power.

Thank you for helping me with this stuff. I mean that.

Raucous Indignation@#17:

I always feel so ill-educated when I post early in one of your threads and then go back and read the rest of the comments. But then you go on about Sithrak, and all is well again.

How do you think I feel!?

We’ve all got to have something to do while Sithrak’s sharpening the spit.

Didn’t Townes VanZandt write a song about that…?

tkreacher@#18:

I read a lot of philosophy and religion, and was frustrated that so little of it stayed on a line I found reasonable and reached conclusions I thought were justified.

That sounds similar to me. I read a lot of philosophy and took some undergraduate-level courses in college. I read a lot of stuff. I concluded it was running around in circles – there are a lot of valuable thinking tools in philosophy and it’s a useful discipline. But I’m a person who enjoys building things, making things that work; my takeaway is that philosophy is more of a tool for destroying things than creating them. I know that’s an unfair overgeneralization, but extreme skepticism is a damn fine weapon for ripping things up.

In 2009, when the tech world (and the rest of the economy) was heading into the toilet, there wasn’t a lot of demand for pricy consultants and I wound up with the whole winter free. So I re-read a bunch of stuff, most notably Lao Tze, Popkin, and (as a good overview) Will Durant, then I got lost in histories of Voltaire and reading about Hume, Rousseau, and the times they lived in (for context). And Plato – dramatized full-cast versions as I’ve mentioned before. I concluded it’s all cracking good stuff but then along came Sam Harris’ book and Richard Carrier – making grand claims about “moral facts” and that ethics could be scientized…

I need to be fair to philosophy and acknowledge that, like psychology, it’s not a unit. There’s some good stuff and some bad stuff. I’m left with my love of learning, and a better sense of the importance of intellectual honesty.

Well, as you pointed out earlier, some people want to be killed while others don’t. There’s nothing generally wrong with assisted suicide. That doesn’t mean I feel as they do, in the sense that I want someone helping me to commit suicide (I don’t, at the moment). I ought to find ways of understanding what they want to have done for them, not what I want to have done for me, since these are different things. Sometimes, what they want isn’t a good thing to want either, in which case I shouldn’t respect that, although it is generally a good way to approach such situations. But the golden rule, as it’s traditionally formulated, is just stupidity.

I’m not sure I understand what you’re asking. There is a farside of the moon … so what then? Well, then we don’t have a picture of the world in which the moon fails to have a farside, whatever you imagine that picture would be like. We’re allowed to think of it as having a roughly spherical shape, as it appears to be. We’re allowed to think that there is a moon, even though we can’t deduce such things. You don’t get such results, while claiming to be agnostic about such things or in some way doing some kind of waffly maneuver that avoids such things altogether. You either buy into it or you don’t.

Sorry, from here on it’s turning into a longer discussion than I wanted it to be, so the rest of this is just more commentary…. It might be helpful to discuss various things that are seemingly unrelated, but some of the same issues will come up. We’ve been talking about morality for the most part, while only briefly noting causation and other sorts of (non-deductive) scientific or empirical reasoning. I think it’s helpful to see that, if there are any problems with this general approach that I’ve outlined, they’re not just limited to morality but would appear all over the place. That should worry you, if you think there is a problem.

You also need to dismiss radical skepticism about the external world (to give just one example), if you’re going to do anything that’s recognizably science. Nobody’s going around being a Berkeleyan idealist and claiming that there are such things as the moon, in the external world, separate from their idea of it (or God’s idea of it), then proceeding to do normal science about that idea. That would not work out very well. So if we’re not allowed to dismiss it for the same basic reasons, we’d run into a lot more trouble then as well, just as we would when putting together an adequate metaethics. If you think there is a world that “impresses” things upon us, then you’ve left all of that skeptical crap behind and can go about your business normally. The simplest explanation why our impressions seem to present a comprehensible world to us is that there is a comprehensible world for them to be about. The simplest thing is that they’re more or less true, not just that they seem to be true. So you just run with that and do all sorts of productive/useful things with it, before anybody tries to ask how you deduced this (because you can’t deduce it — you infer it abductively or inductively or what have you). If there isn’t anything preventing you from doing that responsibly, then you don’t run into a problem.

There’s a modern view about natural/physical laws, which isn’t something Hume talked about explicitly but is called “Humean” because it’s more or less following through with his objections to the naive or intuitive way of thinking about causation. It’s very natural to talk about laws, like F=ma, as if they are some extra thing in addition to the particular facts of the world, which impose requirements on the world that it behave this way rather than some other way. They’re laws that need to be obeyed, like civil laws. You might even imagine that if an object moved the wrong way, so as to violate the law, it would be punished — or it’s too afraid of this punishment to ever do that, so it always acts in accordance with the laws which govern how the world works. What a good little obedient object it is.

A Humean would say, no, that’s an extremely silly way to think of it, that isn’t really what’s going on, you shouldn’t take the word “law” literally, that’s just a figure of speech, and so forth. You need to back way up with this nonsense and not get carried away with it in the first place. The right story is that people come up with true, useful, informative summaries of all of the particular facts — these things say the behavior of the world is like this. Laws aren’t something extra, which exist over and above the facts. They aren’t governing the world in some sense like God is supposed to be governing the world. They’re statements we come up with to represent all of it with math and language and so forth, in the simplest possible terms, in a way that we can use to understand all of the very complicated stuff that we’ve learned is happening in the world.

So here’s one thing to notice: a Humean definitely isn’t saying the laws are not true or that things don’t really work that way. They’re not claiming that there don’t even exist a bunch of particular facts for our laws to summarize. There is a world, and there’s no reason to think we can’t be realists about all sorts of things like this. Maybe we don’t know them, maybe there are many different and equally-good ways to formulate them, and we just happened upon one of them rather than any others, etc. None of it means we have good reason to be skeptical of such things. It’s just pointing toward a more appropriate way of thinking about them, which is better because it isn’t introducing a lot of unnecessary confusion. That’s what you get out of it: less confusion, better/clearer understanding, a somewhat more sophisticated view which doesn’t create problems for you, things of that sort. Good, reasonable, practical, common sense philosophy, instead of useless sophistry. That’s not nothing.

The fact just is that things do what they do, or that A happens then B happens. You need to be careful about how you’re conceptualizing that. But you also don’t want to be too hasty about what you’re tossing out of the picture — you’re not getting rid of all of it, merely because you “can” (or think you can), only the clearly mistaken bits that create the clear problems. If you can’t respectably hold onto some ideas you’ve been entertaining your whole life, that’s just saying you have some good reasons to get rid of those. But there’s no reliable or practical way of systematically removing everything then building up from scratch all of the real stuff we need, as if you were Descartes and pretending like you could doubt (nearly) everything. You wouldn’t get very far with that process at all (although Descartes thought he got all the way to the existence of God, in just a couple of pages). You can get much farther, as many people have in modern history, by first of all exercising some common sense and then pushing on it as hard as you can to see where it starts falling apart. And if you’re not going to get anywhere by pushing on some part of it, then why bother? Your time is better spent pushing on something else.

I think you do a good job of demolishing Harris’ arguments.

However, I think that a better philosopher could suggest a more objective foundation for a system of ethics than Harris manages in the sections you quote. The one who does the best job seems to me to be John Rawles, with his argument that the way to tell whether a society was in a desirable state or not (“flourishing” in Harris’ terms) would be to imagine yourself participating in such a society, without knowing in advance what place you might hold in it.

If you put in that addendum into Harris’ system (instead of his ill-defined “flourishing,”) then it would seem to answer your defense of the “beating people in cloth bags” culture and the “blinding every third child” culture — you can safely criticize such cultures by arguing that the benefit if one should find oneself the beater or the non-blinded would be more than canceled by the detriment should one find oneself ending up as the bag victim or blinded one.

To get there, you’d still need to accept some sort of premise like “The purpose of ethics is to improve the human condition,” with the definition of improving the human condition being the creation of a society where, as Rawles might say, you don’t know who you might wind up being. I don’t think that premise is too much of a stretch, though. So far, it’s the best system of political philosophy I’ve come across.

brucegee1962@23:

I agree about Rawls. So, what happened there? I read The Law of Peoples and I think the establishment decided he was anti-capitalist and anti-establishment after that. Shockingly globalist, too. We can’t have that sort of thing, he was practically a communist. Dewey was another philosopher who was very influential until he became tinged with a bit of red around the edges and marginalized.

“The purpose of ethics is to improve the human condition,”

Why isn’t the purpose of ethics to improve the condition of bacteria? There are so many of them and they are much less demanding. Etc.

(instead of his ill-defined “flourishing,”)

But the virtue ethicists have to introduce “flourishing” or “virtue” into their system, because otherwise there’s no way for them to beg the question! If one had a good definition of “flourishing” or “virtue” one could stick a gold star on it and call it an ethical system right there. I’m probably misunderstanding something but it has always seemed to me that Aristotle got a pass for making circular arguments because he was Aristotle. And that still doesn’t address the person who doesn’t agree and would prefer to see whatever amount of human suffering was necessary for his personal flourishing. That position is usually strawmanned as Nietzsche’s nihilist, but really it’s more like a corporate CEO …

What happened to Rawls? Well, I have a hunch… I think a lot of people really didn’t like the implications of his argument that you shouldn’t get to benefit unfairly from the arbitrary conditions of your birth – like how smart you are, or how rich your parents were. A lot of people – particularly people who like to talk about philosophy – like to think that (a) they’re really smart, and (b) that makes them better* people who deserve nice things. When Rawls points out that it just makes them luckier people, and that actually if anybody deserves nice things it’s people who work hard despite not being born with all the advantages, that harshes their buzz. I know that I found it a pretty nasty kick in the complacency when I first really processed that idea…

Obviously a lot of people (particularly establishment types) really didn’t like the implications for inheritance (and by extension inheritance taxes) either.

(* “Better” in this context tends to oscillate rapidly between “more able” and “morally superior” depending on how closely you’re looking at the time.)

consciousness razor@#22:

We’ve been talking about morality for the most part, while only briefly noting causation and other sorts of (non-deductive) scientific or empirical reasoning. I think it’s helpful to see that, if there are any problems with this general approach that I’ve outlined, they’re not just limited to morality but would appear all over the place. That should worry you, if you think there is a problem.

You also need to dismiss radical skepticism about the external world (to give just one example), if you’re going to do anything that’s recognizably science

Yes, I caught that. That’s what I meant when I said that Hume was playing a bigger game; radical skepticism completely puts the brakes on all knowledge. I’m not a pyrrhonist though I recognize the power and usefulness of their tools. (It appears that even the pyrrhonists lived that way – even radical skeptics still pause to appear to pee)

I don’t want to drag you afield and I’ve taken lots of your time, so I’ll try to keep from the epistemological sand trap. Popkin, I think fairly, doesn’t shoehorn Hume as a skeptic except in so far as that he was concerned with the method of skepticism. I ought to dig up a section from Popkin and post it; he was tremendously influential on my thinking.

So here’s one thing to notice: a Humean definitely isn’t saying the laws are not true or that things don’t really work that way. They’re not claiming that there don’t even exist a bunch of particular facts for our laws to summarize. There is a world, and there’s no reason to think we can’t be realists about all sorts of things like this. Maybe we don’t know them, maybe there are many different and equally-good ways to formulate them, and we just happened upon one of them rather than any others, etc. None of it means we have good reason to be skeptical of such things. It’s just pointing toward a more appropriate way of thinking about them, which is better because it isn’t introducing a lot of unnecessary confusion. That’s what you get out of it: less confusion, better/clearer understanding, a somewhat more sophisticated view which doesn’t create problems for you, things of that sort. Good, reasonable, practical, common sense philosophy, instead of useless sophistry. That’s not nothing.

Agreed. (And that was beautifully put)

This has been a very educational discussion for me, and has clarified some things. I’ve got to circle back (not to draw you back in) to the reason why Hume got dragged into this whole sordid mess of Harris’ – the “Ha! Refuted Hume!” move, which, I think we’re agreeing, misses the point. Both Harris and Carrier made this trumpets blaring entrance saying “there are moral facts!” as if that somehow means – I dunno even what – great victory for humanism? No, it seems that if we have moral facts it means that we can argue our interpretations of those facts more or less exactly as we always have back in the day when we thought they were merely moral intuitions.

Dunc@#25:

I think a lot of people really didn’t like the implications of his argument that you shouldn’t get to benefit unfairly from the arbitrary conditions of your birth – like how smart you are, or how rich your parents were.

Looks like we were sharing a brain-wave! Yeah, I agree: Rawls was kind of an SJW and probably anti-capitalist and anti-aristocrat to boot! That whole thing about building fairer societies, it’s treading perilously close to the S-word or even the (whispering) C-word.

Your mission, if you’re creating a system of ethics, is for it to resolve differences of opinion about what people believe they should do.

As if that’s ever going to happen!

To accept such a system of ethics, people would have to first accept a bunch of assumptions:

– It’s not just my wellbeing that matters, other people’s flourishing matters too. *Narcissists and sociopaths seem to disagree.

– Every human being’s flourishing matters. *Racists, sexists, nationalists, homophobes and so on seem to disagree.

– What increases or decreases human flourishing should be determined by scientific data rather than religious dogmas. *All religious people seem to disagree.

– All humans are going to learn correct scientific facts. *For example, anti-vaxxers seem to believe that vaccines are harmful for children (a false fact that their opinions are based upon).

– Science can determine and predict outcomes of actions, thus enabling humans to know what consequences their actions will have. *This is where I disagree.

– Human wellbeing is quantifiable. When we know that an action is going to have both positive and negative consequences, it is possible to rationally compare gains and losses, thus making a sound conclusion about whether this action is good or bad. *Again, I disagree.

I’d say it is pretty impossible to resolve differences of opinion about what people consider good or bad actions. Good luck trying that!

I agree about Rawls. So, what happened there? I read The Law of Peoples and I think the establishment decided he was anti-capitalist and anti-establishment after that. Shockingly globalist, too. We can’t have that sort of thing, he was practically a communist. Dewey was another philosopher who was very influential until he became tinged with a bit of red around the edges and marginalized.

Rawls’ original position thought experiment demands you to agree that the wellbeing of all living beings matter and it is not OK for one person to abuse or exploit another. And simply accepting this idea forces you to become (at least to some degree) anti-establishment. Currently majority of humans on this planet are subject to at least some forms of abuse or exploitation. If you decide that you care about the wellbeing of all humans, you are bound to want at least some changes, thus turning against the established situation. And even deluding yourself that “all poor people are living in misery only because they are lazy” and “everybody who works hard can get a sweet life” can’t help this. Children in poor families suffer too, and you cannot say that a child deserves to suffer because her parents “are lazy” (after all, you wouldn’t like to be born as a child who suffers yet is unable to change her situation).

And that still doesn’t address the person who doesn’t agree and would prefer to see whatever amount of human suffering was necessary for his personal flourishing. That position is usually strawmanned as Nietzsche’s nihilist, but really it’s more like a corporate CEO …

Yep, and this is where ethics tend to end up getting stuck: “I’m white, rich, born in the right place and with the right body, so screw all the arguments. I’m happy!” I find opinions about moral philosophy fun to read, but ultimately it all ends up with most people ignoring all the noble ideas and doing whatever the hell they want.

Speaking of ethics in general. I have had really bad luck with ethics professors. The first time I got an ethics class at school, I got a teacher who just proclaimed a bunch of assumptions stated as “X is good, Y is bad, you must do X”. Of course those assumptions were heavily based upon Christian values. I didn’t like the class at all. Then some years later I ended up debating against an ethics professor (it was a debate about a political issue). Her argument was basically, “I’m an ethics professor, I have a Ph.D., therefore my position is correct.” She actually got quite angry when I presented my arguments and the debate ended with her calling me an envious communist. So Sam Harris has got some quite fitting company. People who talk about ethics tend to have the nasty habit of just coming up with whatever and claiming that as facts. For their credit, it’s not like it’s easy to defend moral opinions.

By the way, I was wondering. In that picture with philosopher portraits with “wut??” on the images, why is there “VAT??” on Nietzsche’s photo? What does “vat” mean?

Dunc @#25

I think a lot of people really didn’t like the implications of his argument that you shouldn’t get to benefit unfairly from the arbitrary conditions of your birth – like how smart you are, or how rich your parents were. A lot of people – particularly people who like to talk about philosophy – like to think that (a) they’re really smart, and (b) that makes them better* people who deserve nice things. When Rawls points out that it just makes them luckier people, and that actually if anybody deserves nice things it’s people who work hard despite not being born with all the advantages, that harshes their buzz.