Sextus Empiricus’ “Outlines of Pyrrhonism, Part 1” Chapter 15:

Of the Five Modes

The later Sceptics hand down Five Modes leading to suspension, namely these: the first based on discrepancy, the second on regress ad infinitum, the third on relativity, the fourth on hypothesis, the fifth on circular reasoning.

That based on discrepancy leads us to find that with regard to the object presented there has arisen both amongst ordinary people and amongst the philosophers an interminable conflict because of which we are unable either to choose a thing or reject it, and so fall back on suspension. The Mode based upon regress ad infinitum is that whereby we assert that the thing adduced as a proof of the matter proposed needs a further proof, and this again another, and so on ad infinitum, so that the consequence is suspension, as we possess no starting point for our argument. The Mode based upon relativity, as we have already said, is that whereby the object has such or such an appearance in relation to the subject judging and to the concomitant percepts, but as to its real nature we suspend judgment. We have the Mode based on hypothesis when the Dogmatists, being forced to recede ad infinitum, take as their starting-point something which they do not establish by argument but claim to assume as granted simply and without demonstration. The Mode of circular reasoning is the form used when the proof itself which ought to establish the matter of inquiry requires confirmation derived from that matter; in this case, being unable to assume either in order to establish the other, we suspend judgment about both.

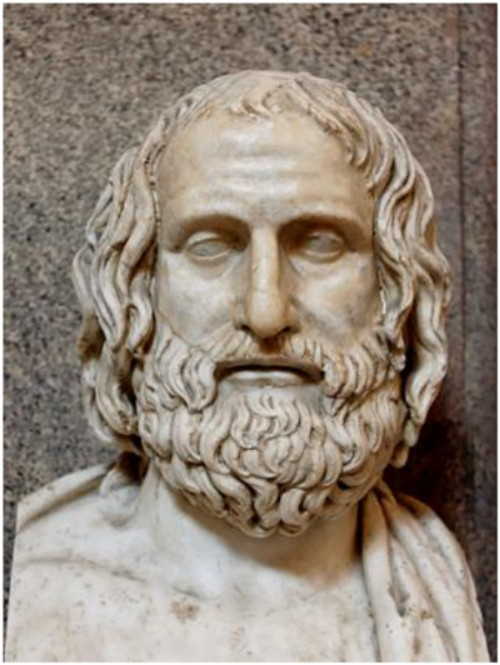

Sextus Empiricus

The philosophers of yore used to collect weaponized arguments, sort of like how “pick up artists” nowadays collect tricks and come-on lines. It gets interesting to try to figure them out, there’s a great deal of cross-posting going on, “and so-and-so argued such-and-such which is absurd because of reasons” Sextus Empiricus’ “outlines of pyrrhonism” explains the techniques of radical skepticism: focus on appearance and evidence of the senses, withholding of judgement about what is true or correct, interposition of personal experience in lieu of general epistemology, and observation of the unreliability of sensory input (while arguing that it’s all we’ve got). If you’re ever in a discussion with someone and they start dropping a strange sort of waffly-sounding sentence structure like, “it appears to me now that…” or “it would seem that” you may be about to get hit with some pyrrhonism. Pyrrhonists avoid making “dogmatic” statements, i.e.: statements of fact.

Someone says, “It is raining.”

The pyrrhonian says, “It appears so.”

Notice the pyrrhonian is careful not to offer a statement of fact, because once you offer a statement of fact, you can be thoroughly pounded on your epistemology and then the discussion is over. Pyrrhonism ends discussions. Or, should I say, “it appears to me that when pyrrhonism is introduced into a discussion, the discussion ends.”

The pyrrhonians have several lists of modes of argument, compiled in Sextus Empiricus, but we’ll look at this list because it’s short, clear, and useful. Diogenes Laertius later credited Agrippa the Skeptic with these 5 modes.

Disputation, Mode 1) That based on discrepancy leads us to find that with regard to the object presented there has arisen both amongst ordinary people and amongst the philosophers an interminable conflict because of which we are unable either to choose a thing or reject it, and so fall back on suspension.

The skeptic remains unconvinced of anything, and and suspends judgement (“suspension”) as to whether any particular view is true or false. (“choose a thing or reject it”) This is classical skepticism: until you’ve convinced me of something, I can’t say what I think, so I basically shrug my shoulders and say “I hear your words but I’m not convinced, yet.”

In this mode – “Disputation”, the skeptic observes that one can find someone who disagrees about anything, and that anything can and is disputed, probably for good reason, therefore it’s best to just suspend judgement and wait to see if the disputes ever end.

Someone: “The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain.”

Skeptic: “That’s interesting, Sam Harris says that the rain in Spain falls mainly on fridays.”

Someone: “No, I am referring to where the rain falls, not when.”

Skeptic: “In Matthew 5:48, it says that the rain falls on the just and the unjust alike. Does that apply in Spain as well.”

Someone: (head explodes)

Infinite Regress, Mode 2) The Mode based upon regress ad infinitum is that whereby we assert that the thing adduced as a proof of the matter proposed needs a further proof, and this again another, and so on ad infinitum, so that the consequence is suspension, as we possess no starting point for our argument.

Someone: “The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain.”

Skeptic: “How do you know that?”

Someone: “Wikipedia says that Spain is mostly plain, therefore rain must mostly fall on the plain.”

Skeptic: “Why do you believe Wikipedia is right?”

Someone: “Wikipedia is crowd-sourced and if anyone made a mistake it would get corrected eventually.”

Skeptic: “Why do you believe that the corrections would be correct?”

Someone: (continues until someone dies of old age)

Relativity, Mode 3) The Mode based upon relativity, as we have already said, is that whereby the object has such or such an appearance in relation to the subject judging and to the concomitant percepts, but as to its real nature we suspend judgment.

The skeptic observes that many things appear to be different relative to how we look at them, and when. This calls into question our ability to make certain kinds of claims about those things.

Someone: “The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain.”

Skeptic: “It appears that way, right now, but couldn’t it be just that you are standing in the plain right now?”

Someone: “Yes, but you are standing in the plain with me, as well!”

Skeptic: “It seems that if we were standing in the Plaza in Madrid, it might appear to be raining in the plaza and we would then be unable to know if it is raining in the plain.”

Someone: (leaves)

Hypothesis, Mode 4) We have the Mode based on hypothesis when the Dogmatists, being forced to recede ad infinitum, take as their starting-point something which they do not establish by argument but claim to assume as granted simply and without demonstration.

In order to avoid going into infinite regress (mode 2) the opponent offers a hypothesis, and is immediately challenged that the hypothesis is, as a hypothesis, well and good, but we must withhold judgement about the entire proceeding.

Someone: “The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain.”

Skeptic: “How do you know that?”

Someone: “Let’s just accept that as a hypothesis and move on.”

Skeptic: “I grant that it’s a hypothesis. It’s a fine hypothesis. But, as a hypothesis, it’s unconvincing.”

Circular Reasoning, Mode 5) The Mode of circular reasoning is the form used when the proof itself which ought to establish the matter of inquiry requires confirmation derived from that matter; in this case, being unable to assume either in order to establish the other, we suspend judgment about both.

This mode is particularly effective against the opponent’s vocabulary, if you get into a war of definitions.

Someone: “The rain in Spain falls mainly on the plain.”

Skeptic: “What is ‘Spain’?”

Someone: “It’s a country that includes mountains, cities, and plains.”

Skeptic: “What are the ‘plains’?”

(eventually)

Someone: “The plains in Spain are the largest part of the country.”

Skeptic: “You appear to me now to be making a circular argument.”

The pyrrhonist skeptics came up with a technique for never losing an argument, by resorting to a series of epistemological challenges that successively demolish their opponents’ ability to make any claims of fact. It’s a way to deny your opponent an opportunity to win, using a sort of “Kobayashi Maru”* redefinition of the engagement. The downside is that the skeptic self-prohibits from making any claim of fact, so they can’t even say “I won the argument!” – the best they can say is “I appear to have won the argument.” It’s avoiding the discussion by resorting to meta-discussion; the skeptic is gaming the argument and is not being an honest interlocutor.

What I take away from studying the pyrrhonists is that, when your opponent starts unleashing epistemological tricks on you, it’s time to go for lunch. With someone else. Some of the underlying issues raised in the modes and tropes of the pyrrhonians are interesting: yes, there is a question “how do you know that?” which is worth asking. But even Socrates did it carefully, by encouraging his opponents to clarify their definitions.

Sextus Empiricus “Outlines of Pyrrhonism” translated with commentary by Benson Mates (Page 30) (amazon.com)

More analysis of Sextus Empiricus in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

(* I understand that later Star Trek canon had the Kobayashi Maru puzzle solved by Kirk hacking a computer. That’s incredibly lame and I’m very sad that they did that; it was much better to imagine that Kirk had solved the tactical problem by doing something that was utterly outside the rules, which resulted in a win by causing the scenario to go no further. Kirk’s original “redefining the problem” approach – whatever it was – is a lot better than winning through cheating.)

It’s interesting how similar these techniques are to the corresponding logical fallacies. It looks like the pyrrhonists found a way to turn every claim by their opponent into a fallacy.

DonDueed@#1:

It looks like the pyrrhonists found a way to turn every claim by their opponent into a fallacy.

That’s a really good way of putting it!