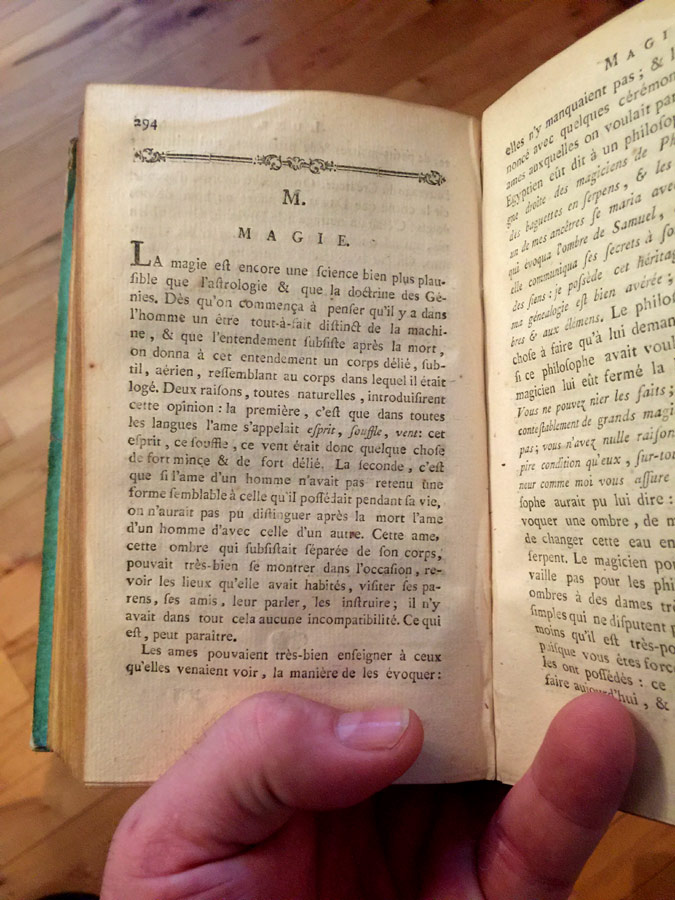

Magic is another science that is as plausible as astrology and the existence of genies. (Ivo@comment #9 corrects my translation. It should read: Magic is another science much more plausible than astrology or the doctrine of Genies.)

Voltaire by Houdon

As soon as one begins to think that there is, in man, a part that is separate from the mechanism, which persists after death, we imagine that fancy to be detached, subtle, floating, resembling the corpse from which it was detached. Two reasons, both natural, introduce this opinion; first is that – in all the languages, the soul is called breath, wind, pneuma, this breath, wind, spirit must be made of something very insubstantial indeed. The second is that the spirit of a man doesn’t hold the shape that they were in when they were alive – we can’t, after death, tell the soul of one man from another.

Voltaire was a believer in the soul, he was not an atheist. Yet he was corrosively skeptical about practically everything – as I read this entry I feel like I can sense his struggle; he wants to call it all ridiculous but to preserve what little faith he has, he cannot.

It’s interesting that he jumps from magic to the soul; for a person of his time, I suppose the one depended on the other.

Hm.

If “magic” is considered as a synonym with “supernatural”, Richard Carrier’s essay on defining the supernatural accords with Voltaire, to some extent.

That is, Carrier suggests that “supernatural” means “something mental or mindlike that cannot be reduced to the non-mental or non-mindlike”. The usual examples of the supernatural are God and ghosts; spirits; souls (those terms might not all be exactly synonymous, but if they are not the same, they could all be different examples of something irreducibly mindlike).

Do you have any personal thoughts on the concepts of “magic” or “supernatural”?

Owlmirror@#1:

Do you have any personal thoughts on the concepts of “magic” or “supernatural”?

I remember trying to get through Carrier’s piece, and I had a lot of trouble with parts of it. To me, it was off-putting to see terms that imply non-existence mixed up with terms that imply existence. For example saying “the supernatural is” seems to me to be a contradiction in terms – that which is natural is that which exists and can be observed or measured to exist. Something supernatural, therefore, doesn’t exist. What Carrier seems to me to be doing is similar to the woo-woos who are imagining things and saying “because I imagine it, to that extent, it exists.” To the extent there are signals in someone’s brain, that’s the extent to which imagined things exist.

I guess I’m a skeptic in the epicurean or humean form: if I don’t see any reason to believe something exists, I assume it doesn’t. If someone comes to me and swears they’ve seen a ghost I probably will believe that they are telling me they saw a ghost – but I won’t believe they actually did because seeing requires certain properties, including “existence” So, if I see something that looks like a ghost, it’s a material object of some kind that I simply do not understand. Yet.

I think that’s a basic hardline skeptical position: things exist and I don’t even want to say “things don’t exist” because something that doesn’t exist isn’t even a “thing.”

I wrote a piece about ghosts a few years ago (I do believe in ghosts, actually, for some definition of “ghost”) I have been meaning to revisit and rethink it for a while.

Carrier writes things like (just grabbing bits at random)

“substance” and “supernatural” are a contradiction in terms. “Substance” literally means “material” – i.e.: stuff. Stuff that exists. I can accept that “supernatural” means “outside of nature” – but when I think of that all I come back with is “nonexistent.” That’s not a criticism of Carrier, BTW – we don’t have language for talking about things that don’t exist because we really don’t need it. I can’t say that the gods are “imaginary” because my imagination exists (that’s what “imaginary” means) but they don’t exist outside of my imagination.

Had some interesting discussions on this very topic back in Pharyngula-that-was.

(I miss truth machine and Sastra)

—

Marcus,

Depends on your ontology.

Concreta and abstracta.

John Morales@#3:

Depends on your ontology.

Sure. If you want to redefine your words so that “substance” means “insubstantial” then there’s no contradiction anymore. ;)

Let’s take unicorns as an example. We can agree that unicorns don’t exist, but are an abstraction. That still doesn’t make unicorns exist; the word “unicorn” exists, the abstraction exists (in our minds) but unicorns stubbornly continue not existing; they’re a figment of our imagination. One can argue, as the christians do, that simply the fact that we can hypothesize god means they exist to some degree, but I’m unconvinced by such argument – the word ‘god” like “unicorn” exists (I just typed it!) and the concept of “gods” exist as an abstraction, but it’s just a word. It’d be hard to convince me that when you say “god” I actually understand you in all respects; the abstract term we’re both using appears to be a collision in a name-space that’s private to each of us. I am unconvinced that shared abstractions are possible (I’m also skeptical about the precision of language)

Abstract concepts are also abstract concepts; they’re real to each of us as we conceive them, to the extent that they exist in our minds as we are thinking about them. It’s imaginary all the way down, unless there’s some way to know eachother’s imaginings. I imagine we could do a vulcanian mind-meld and share an understanding of what we mean when we say “unicorn” but that doesn’t accomplish anything more than us having a shared idea (that doesn’t make unicorns any hornier).

I’m actually pretty comfortable with it appearing that our concern with empiricism is just a side-effect of the impossibility of knowledge, if that’s how it is. Language, as a tool for sharing knowledge, is part of that problem. I’ll use words because it appears that people are able to sometimes understand them enough to appear to (or pretend to) understand what I think I’m saying.

I saw something from Sastra fairly recently, I think. Truth Machine, yes, an interesting and very focused commenter. Haven’t seen anything from them for a while.

Marcus, for a bit of fun:

Existence is a bit trickier than that. Consider:

Let’s take Tyrannosaurus rex as an example. We can agree that Tyrannosaurus rex don’t exist, but are an abstraction. That still doesn’t make Tyrannosaurus rex exist; the word “Tyrannosaurus rex” exists, the abstraction exists (in our minds) but Tyrannosaurus rex stubbornly continue not existing; they’re a figment of our imagination.

(Just as true as what you wrote, no? )

John Morales@#5:

Tyrannosaurus rex stubbornly continue not existing; they’re a figment of our imagination.

That’s a great example!

Because, you may be thinking “fossils! T-rex fossils exist, and those are technically T-rexes” But nope, they’ve pined for the fjords and shuffled off, etc. They’re an abstraction about something that used to exist and no longer does. We can imagine them (and often do!) but unless you know something about what really goes on in PZ’s lab, T-rexes do not exist.

Ideas of T-rexes exist in many many of our minds. But it’s just an idea and it’s not even shared knowledge. Some of us who grew up in the 60s see T-rexes as being putty-gray without feathers. Others see T-rexes with feathers and coloration. Every idea everyone has about T-rexes is more or less informed, more or less accurate, and the ideas are just how particular brains fire when they see the word “T-rex” or hear it. Since T-rexes no longer exist, I’d say that those brains are all experiencing being mistaken.

I’ll go out on a limb here and say two things: that imagined abstraction is what I’d call a “ghost” if someone asks me “do you believe in ghosts?” In some people’s case the distinction between the imagined abstraction and the imagined reality breaks down and they can’t tell which is which. That doesn’t mean ghosts exist, it just means that for some people, sometimes, their ability to distinguish what exists and what does not exist, breaks down. If I am blind and am walking toward a bottomless plungehole, and nobody tells me about it, it doesn’t exist for me until I discover it. If you interrupt my trajectory and tell me “STOP! there is a bottomless plungehole!” I will maybe have an abstract idea of a bottomless plungehole but it’ll certainly be different from the reality (remember, I’m blind) I’ll observe here that as we learn more about how brains interact with reality, it appears that they build a representational model of whatever they are able to learn about reality, however they learn it, and then place “us” as a bookmark of sorts in that model. The model appears to be updated asynchronously, which makes sense when you consider that our eyes don’t see as fast as our ears hear, yet that model synchronizes our perception of those events.

There appears to be some external stuff that exists, because many of us appear to observe it and agree about some of its properties (though: consider the story of the blind men and the elephant) but it seems impossible, to me, that we actually are all sharing the same experience of existence if only because you’re not standing in my shoes, my eyes aren’t very good, etc.

Addendum: I think that “reality as an idea about reality” explains certain forms of confusion in which people see things that nobody else does (because often, the things don’t exist) Someone who is experiencing delusions or tripping on psychoactives can be experiencing things that are “real” to them but do not actually exist. I always liked Philip K. Dick’s “Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” If I’m blind and I’m walking toward a bottomless plungehole, and you tell me “you are heading for a bottomless plungehole!” I may experience an abstract thought of the bottomless plungehole, decide I don’t believe you, keep walking, and then I will experience something completely different from my abstract imagined bottomless plungehole.

I don’t know if you’ve ever experienced when your brain and your eyes/imagination/representation of reality get out of sync. One situation I recall vividly is when I lose track of how many steps are left on a flight of stairs and try (believing there is a stair there!) to step up into the air. It’s really shocking! The brain does a great big WTF and scrambles to reassemble that representation. Another time I fell through a trapdoor that was open, which I thought was closed, in the dark. Suddenly I was falling! It was utterly disorienting. I suspect that a blind person falling into a bottomless plungehole that they didn’t believe in would experience something similar. Lucky me, I only fell 6 feet.

Lately I’ve been playing around with VR goggles and stuff (HTC Vive) and had a rather interesting thing happen the other day. A friend who was using the goggles was looking over the edge of a “cliff” and was lying on the floor on her belly, craning just her neck over the edge so she could look down. I tried it later and the illusion was very convincing. When she was standing, I tried to talk her into going off the edge, “no way.” I asked if I could pick her up and carry her off the edge. “no!” Then she thought about it and – I guess she was making a new representation of herself in her imagination, of her with the goggles on standing in her living-room, and somehow substituting that for the representation of herself looking over the edge of a chasm. We were both able to talk ourselves into stepping off the “edge” eventually.

Did the edge exist? (I say No: an imaginary edge existed in each of our minds, which is to say that the edge did not exist, but our thoughts about the edge did)

Glad you had some fun, and thanks for playing along (it’s rare).

An old conundrum in philosophy, addressed by the concept of categories of being.

(Or, the edge was real enough in a phenomenological sense, if not in a veridical one)

—

On the OP, I like Clarke’s Third Law — but though it works for magic, it doesn’t work for Gods (perhaps for gods, though :) )

Just nit-picking on the translation from French. The first sentence actually says:

This seems to me rather different from “as plausible as”. N’est-ce pas ?

I used to think something like the above, but it’s a bit problematic when you think about the concept of the supernatural in popular usage. People who believe in the supernatural obviously believe that the supernatural exists, so your definition of “natural” and “supernatural” cannot possibly be what they have in mind.

I think that people who believe in the supernatural are very confused, but I don’t think they are so confused as to think that something that doesn’t exist by definition, does exist. They’re using a different concept of natural, and therefore of supernatural.

There are some thirty definitions of “natural”, so it seems quite natural (heh) to me that confusion will arise. But we should strive to be less confused. Which is what I think Carrier is trying to do. He may be missing something, and I’ve been trying to work out what it might be, but I don’t think he’s completely wrong.

What? No, not at all. Carrier is an atheist who does not believe in the supernatural. All he’s doing is emphasizing that the term “supernatural” isn’t meaningless (or synonymous with “nonexistent”).

I see him as saying something like: “We can imagine phenomena, which, if they actually existed, would be properly defined as being supernatural.”

I think we do have language for talking about hypotheticals, counterfactuals, and concepts that are ambiguous or deeply confused. And if we don’t have such language, we need to, because many people do believe counterfactuals. I really don’t think you can convince a theist or other supernaturalist that there’s anything wrong with what they believe by arguing “What you believe is false because it is nonexistent by definition” — all they need to do is retort: “Your definition is wrong!”. You haven’t gotten anywhere, except maybe convincing them that you are the confused one.

One more point:

You can imagine a horse, a human, and a centaur. Just because you’re imagining horses or humans does not mean that horses or humans don’t exist; just because you’re imagining centaurs does not mean that centaurs do exist. Clearly, you need a way to distinguish between what you can imagine that does exist and what you can imagine that does not exist.

A theist imagines that God or gods are existent, but what makes them wrong? Any argument needs to point out problems with what they imagine.

@John Morales:

“Any wielder of sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from a god.”

(You might say “Why a god rather than a wizard?”, and I might reply “How sufficiently advanced are we talking about?”)

Marcus Ranum @ # 2: … saying “the supernatural is” seems to me to be a contradiction in terms …

Time for a basic review of the predicate: as W.J. Clinton observed in the coded message that the time had come to unveil the organization now known to some as Daesh, “It all depends on what is is.”

In one context, that double-edged two-letter word connotes existence (“it is what it is…”); in another, it serves as an = sign (“the supernatural is imaginary…”). My dictionary widget shows three primary meanings and 10 secondary usages, plus four major variations as an auxiliary verb.

Personally, I try to keep my thinking clearer by use of E-prime whenever practical.

Ivo@#9:

Magic is another science much more plausible than astrology or the doctrine of Genies.

You’re right. I completely brain-farted on that one. It’s especially annoying since “bien plus” is pretty common. I’m not sure how I got that so wrong.

I’m going to correct it with a link.

John Morales@#8:

An old conundrum in philosophy, addressed by the concept of categories of being.

(Or, the edge was real enough in a phenomenological sense, if not in a veridical one)

Yes. And I understand the usefulness of having specialized language for philosophers to be able to talk about the contradiction between “real” and “real to me” It seems to me that we have adequate vocabulary, already – I’m trying to express myself without resorting to another layer of terminology, because I think that the problem is already in whole or in part a matter of terminology and besides I think we can do just fine with the use of “imaginary” For example: “imaginary unicorn” versus “real unicorn.”

(a real unicorn would bring up some interesting questions because some people might not agree, anyway. What if someone thinks all unicorns are white and fart rainbows and a real unicorn walks up to them and is non rainbow-farting, big and black and unicorned? I would say there is a real unicorn and it doesn’t match their imagined unicorns, but only if I thought unicorns could be big and black)

Owlmirror@#10:

Carrier is an atheist who does not believe in the supernatural. All he’s doing is emphasizing that the term “supernatural” isn’t meaningless (or synonymous with “nonexistent”).

Yeah, I know Carrier’s an atheist. And I know he’s emphasizing that he believes the term “supernatural” isn’t meaningless (and that he doesn’t find it synonymous with “nonexistent”) I don’t buy his argument, that’s all. We can get down into the weeds and argue about definitions, which is really what we’re doing, but definitions appear to me to eventually become circular and in this case, my definition of “supernatural” would come out as “imaginary” whereas Carrier’s would not.

it’s a bit problematic when you think about the concept of the supernatural in popular usage. People who believe in the supernatural obviously believe that the supernatural exists, so your definition of “natural” and “supernatural” cannot possibly be what they have in mind.

I agree. It can’t.

The argument that “everyone’s doing it” doesn’t carry a lot of weight with me. Sure, and there are lots of people who abuse language in other ways. So what? Appealing to popular usage seems like a bad move; in my opinion it’s appealing to popular usage that makes us have to have this discussion at all.

They wish to use the word “supernatural” to imply something that exists that is outside of or superceeding or on another level of existence than nature. Something like that. Well, there’s no way to learn anything about those things, because they don’t betray any of the properties of something that exists. You can’t see them (seeing requires absorbing and releasing photons) you can’t touch them (touch requires contacting them and generating nerve impulses) you can’t hear them (hearing requires making vibrations) etc. The great thing about reality is that being able to touch something means it’s interacting with photons and vibration as well – the whole great panoply of conservation laws applies to it. And – aside from imaginary things anything that exists is going to do all that stuff that things that exist do. I’m with the epicureans and the pyrrhonians that there’s know way to know anything about something except through our senses. So if there’s an alternate plane of existence it’s unknowable because if we can know anything about it, then it’s just part of existence.

Again, I understand that people like to use the word “supernatural.” Maybe even Richard Carrier does. So what? People like to say “duh” and “um” too and “supernatural” seems to me to make just as much sense.

Where it may make some sense is if you talk about imagination, as we’ve been doing. If John Morales tells me “there is an alternate plane of reality, where the streets are paved with gold” – OK, I now have imagined an alternate plane of reality and I can imagine gold streets. But I got my information about that through my senses, in the form of words, conveniently arranged to convey a tiny fragment of his imagination to mine. That’s what’s going on with “supernatural” – and that’s what I meant when I said it’s similar to certain apologist arguments where the apologist argues that “because you can imagine it, to that extent it’s real.” Because people use the word “supernatural” to that extent the supernatural is real, too. It’s entirely imaginary, i.e.: nonexistent.

I think that people who believe in the supernatural are very confused, but I don’t think they are so confused as to think that something that doesn’t exist by definition, does exist. They’re using a different concept of natural, and therefore of supernatural.

I agree. I’m going to avoid using the term “supernatural” because it seems to me to be contradictory. Other people can continue to use it. I’ll continue to hear them say “imaginary” or “I am full of shit” when they start talking about the “supernatural” unless I drag through the whole epistemology of how they know what they know – which I’ve done many times and it either boils down to imagination or someone else’s imagination transmitted to them in the form of fiction or lies.

There are some thirty definitions of “natural”, so it seems quite natural (heh) to me that confusion will arise. But we should strive to be less confused. Which is what I think Carrier is trying to do. He may be missing something, and I’ve been trying to work out what it might be, but I don’t think he’s completely wrong.

Lots of definitions of “natural” is fine. I don’t see “natural” as self-contradictory.

Carrier’s definition of “paranormal” is:

“What makes something paranormal is the fact that it exists outside the domain of currently plausible science.”

That’s in line with a lot of definitions. I’d use “unknown”; Carrier’s definition implies that the paranormal thing exists which is problematic to me because usually we’re talking about an illusion a misunderstanding or the unknown. In the case of an illusion (as in a magic trick) it’s the subject’s imagination that believes the ball has just come out of the magician’s ear. The subject is misunderstanding what is happening; the trick is unknown.

I also don’t like “paranormal” because, in Carrier’s definition, that would make dark energy “paranormal.” Dark energy is certainly not reasonable or probable (“plausible” in Carrier) and isn’t in the standard model, etc, etc. I don’t think that’s a reductio ad absurdum on “paranormal” but the term has a problem if it applies to phlogiston, magic tricks, and dark energy equally well. (before you go there: they are all rooted in our understanding of physical reality and appear to be violations of it, and are unknown) Carrier points out that someone who didn’t know what snow was, would find it “paranormal” – well, that’s stretching things until they nearly snap. It’s “unknown” and any speculation on the part of the person encountering it is their imagination at work. We don’t need to say it’s paranormal: it’s something we understand or don’t understand.

Carrier’s lengthy digression of the various types of gods, in lieu of a definition of “supernatural” is really painful to wade through. Who gives a shit? They’re imaginary. Next.

In fact, all the stuff Carrier is talking about is imaginary. In this example:

It’s a flower of unknown origin. One can imagine that someone willed it into existence, but it’s not possible to know any of that because we don’t – by definition – have any way of knowing its origin, or its origin would be natural. If Garion creates a flower, and does it again and again in laboratory conditions, stripped naked in a room full of sensors, he fills the room with flowers: the most we can say is “Garion appears to be able to create flowers by some unknown process. Probably a trick.” Unless we want to establish a whole new theory of flowers appearing because of quantum instability. Flowers appearing violates every conservation law (right? The flower has to appear in Earth’s relativistic frame or it’s going to rip a hole in something)

I think we do have language for talking about hypotheticals, counterfactuals, and concepts that are ambiguous or deeply confused. And if we don’t have such language, we need to, because many people do believe counterfactuals. I really don’t think you can convince a theist or other supernaturalist that there’s anything wrong with what they believe by arguing “What you believe is false because it is nonexistent by definition

I’m definitely not arguing that. I’m arguing that, for them to believe what they claim to believe, they are not simply imagining something hypothetical, they’re imagining something that contradicts reality as we understand it. I’m making a basic challenge to their claim to knowledge: how can they say they know anything about something that they just placed outside the realm of the knowable? It’s not my problem, because I’m not making that claim; let them defend it.

Owlmirror@#11:

You can imagine a horse, a human, and a centaur. Just because you’re imagining horses or humans does not mean that horses or humans don’t exist; just because you’re imagining centaurs does not mean that centaurs do exist. Clearly, you need a way to distinguish between what you can imagine that does exist and what you can imagine that does not exist.

I am comfortable saying “centaurs are imaginary.”

I am comfortable saying “I can imagine a horse.”

I am comfortable saying “look! A horse!”

I am comfortable saying “that thing you just told me is a horse, that’s a cow!”

I’m not seeing why I need language extensions in order to make someone happy that I use terminology they don’t consider dismissive to talk about their imaginary things. If it bothers me that I talk about their imaginary centaur like it’s imaginary, I’ll stop thinking of it as imaginary as soon as I meet it and have a beer with it and can maybe get the thing into an MRI. By the way I can actually imagine that someday we might make a centaur. That doesn’t make centaurs “supernatural” they’re still imaginary until they’re not.

Another important thing: I’m also comfortable with talking about “mistaken.”

If I woke up and ran out of my tent without my glasses, I might think that the thing trotting up to me was a centaur, until I got my glasses on. In which case I’d say “I imagined you were a centaur, because I can’t see for crap without my glasses on.” If that happened, we did not have a “paranormal being” appear and then suddenly collapse into being a person on a horse. I was just mistaken. I’m OK with that.

Pierce R. Butler@#13:

Personally, I try to keep my thinking clearer by use of E-prime whenever practical.

Interesting! I hadn’t heard of that.

Language is a real problem. We humans try to build knowledge with such crude tools.

“Any wielder of sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from a god.”

What about stage magicians? I saw Penn saw Teller in half, once, and Teller was reassembled whole.

Was I mistaken, or was that a paranormal event?

Marcus, sorry to be pedantic, but:

You meant to say that it’s only imaginary.

You earlier said that you hold that you have no access to reality except through your senses, which entails that your knowledge about reality is wholly based on inferences from your perception — i.e. it’s entirely a representation within your mind.

In short, everything which is known to be real is also imaginary (a mental representation) — else it would not be known — but not only imaginary.

BTW, clearly one can imagine things not real, so that the imaginary is a superset of what’s real, and conversely what’s real must be a subset of the imaginary.*

As you earlier put it: “They’re [T-rexes] an abstraction about something that used to exist and no longer does. We can imagine them (and often do!) but unless you know something about what really goes on in PZ’s lab, T-rexes do not exist.”

But that’s equally true about things which currently exist, no? And it’s also true about things which can be imagined and perhaps will actually exist in the future.

—

* In passing, I think that the adage that “truth is stranger than fiction” is a really, really silly conceit.

John Morales@#20:

everything which is known to be real is also imaginary (a mental representation) — else it would not be known — but not only imaginary.

Right, yes.

But that’s equally true about things which currently exist, no?

Yes. I can’t remember which ancient philosopher it was (I think Thales or Democritus) who argued that abstractions are both true and false: If I point to a chair and say “that is a chair” it is, but it invokes an abstraction of “chairs(plural)” that exist only in my imagination; I can decide what belongs in that abstraction and what does not, but we do not necessarily have to agree. (Where that example gets weird for me is when we both hear “chairs” and nod, even though if we explored our shared abstraction about “chairs” we might discover that certain things I would call a “chair” you would not, and therefore we do not share the same abstraction, only the word “chairs.”)

T-rexes do appear to have existed, we have bones and stuff from them. They might exist again. If I say “T-rexes!” they may exist only in our imaginations but will probably be subtly different.

The pyrrhonian skeptic would make it even worse by pointing out that even if we were both looking at a T-rex – a non-imaginary one – we wouldn’t both be seeing and experiencing the same T-rex so we wouldn’t really be sharing an idea of T-rex. Besides, you’d be busy running and I’d be fumbling for my camera. Then, when they dug my iPhone out of the bloody grass, and looked at the pictures they’d say “It’s a T-rex!” except it wouldn’t be – it’d be a flat 2-dimensional rendering of a 3D object taken from a particular viewpoint. Sort of like a memory of a T-rex.

clearly one can imagine things not real, so that the imaginary is a superset of what’s real, and conversely what’s real must be a subset of the imaginary

I believe I endorse that statement.

[OT]

I was taken with E’ decades ago, but I’ve found it less amenable than ordinary English to most people if one actually wants to communicate succinctly. These days, I go more by its principles than by its rules, which

areI find impractical.—

Superfluous, but more correct! I do appreciate that.

I was just thinking a bit more about John Morales’ #20, about imagination being a superset of the real. That aligns neatly with another idea, expressed by Rich Rosen “many things are possible, but comparatively few of them actually happen.” It is why we don’t accept hypotheticals without supporting evidence. So when a woowoo says “it is possible that aliens live deep in Earth’s crust” we say “many things are possible, but what is your evidence that that’s happening?” So it seems right to me to acknowledge that the universe of our imagination is limited by our lifetime and creativity, while the reality we each confront is a very small bit of what appears to have actually happened. That reinforces, to me, my decision not to talk about supernatural things: they behave exactly like imaginary things and can be multiplied infinitely like imaginary things. It’s pointless to speculate about an infinity of possibilities or to try to refute them in detail; it’s best to leave the burden of the claim on the proposer. And, as I pointed out earlier, since the only way the proposer could claim to have a cause to believe in something is through their senses, which are natural, anything they claim knowledge of and they claim is supernatural is them contradicting themselves.

@Marcus Ranum, #16:

But why, exactly, would your definition come out as imaginary? I mean, would you really use “supernatural” and “imaginary” interchangably? If not, surely there must be some distinction between those terms that you could recognize. Aren’t there subclasses of imaginary things that you might be willing to agree that its reasonable to subdivide “imaginary” into?

Carrier’s whole point of defining the supernatural is that the supernatural, given the carefully-worded meaning he offers, is (only) imaginary, because what that meaning says about things that actually exist is false, given everything we have discovered about the world by studying the world. It’s a reasonable conclusion, rather than an a priori assumption.

(Now I’m wondering if this is a use/mention problem. Call by reference/call by value?)

You may well be a presciptivist, but do you really think that popular usage has no connection to the meaning of a concept? People who believe in the supernatural are certainly making a mistake, but is it really so unreasonable to try and encapsulate and verbalize the essence of the mistake that they’re making?

(Carrier’s summary of his definition:) If [naturalism] is true, then all minds, and all the contents and powers and effects of minds, are entirely caused by natural [i.e. fundamentally nonmental] phenomena. But if naturalism is false, then some minds, or some of the contents or powers or effects of minds, are causally independent of nature. In other words, such things would then be partly or wholly caused by themselves, or exist or operate directly or fundamentally on their own.

People who believe in the supernatural in some sense believe something fundamental about things that are minds or mindlike. They may well have wrong ideas of what minds are and how they work, but if we understand the mistake they’re making, we can address it directly.

Actually, I don’t think they really have thought it out that well. It seems to be part of the mistake that they’re making.

And — in some cases — they might argue that supernatural phenomena do sometimes have those properties. Ghosts or spirits are sometimes visible, sometimes move things, sometimes emit or absorb heat, sometimes cause vibrations in the air that can be heard. That’s kind of the premise of “Ghost Hunters”. They just won’t let you pin them down on how that whole occasional interaction works.

Actually, I think that goes for their belief in God as well. (“God could generate or reflect photons, or move physical stuff, or make vibrations in the air — he just . . . doesn’t want to do it all the time. He wants us to believe even though he doesn’t do those things on demand, only when he feels like it, which is very very rarely. Something something blah blah free will, because God just loves free will. Do you want to be a robot?”) And like that. Again, they will often utterly refuse to even think about how that whole infrequent interaction works, or resort to quantum handwaving. (“God can alter quantum interactions, so it looks like he isn’t doing anything when he really totally is!”) It’s silly when you try and think about it, but that’s theolology for you.

[I may have more, but I think I’ll break here]

Owlmirror@#24:

I mean, would you really use “supernatural” and “imaginary” interchangably?

Yeah, pretty much. Sort of like I’ve been trying to do through this discussion – if someone starts talking to me about something “supernatural” I refer to it as “imaginary” unless they can convince me it’s not imaginary, i.e.: real. And all the ways of doing that are natural, so whatever it is would then be real.

Aren’t there subclasses of imaginary things that you might be willing to agree that its reasonable to subdivide “imaginary” into?

Sure! As John Morales pointed out up above, you can build a Venn Diagram of imaginary things – things that are real being a subset of all the things that are imaginary. There are also imaginary things that are more real than others, for example, the imaginary group called “brown oak veneer tables” I’d agree that’s more likely to be something we can talk about than “white unicorns” because I’ve seen brown oak veneer tables and never a unicorn.

Carrier’s whole point of defining the supernatural is that the supernatural, given the carefully-worded meaning he offers, is (only) imaginary, because what that meaning says about things that actually exist is false, given everything we have discovered about the world by studying the world. It’s a reasonable conclusion, rather than an a priori assumption.

Carrier’s welcome to use whatever language he likes – that’s the beauty of language!! If he wants to, he can grade imaginary things on a scale of lowest to highest, say an “imagined class called ‘brown oak veneer tables'” all the way to “purely imaginary” or maybe even “11 on the imaginariness dial” (I doubt he’d do that, though) (I should!)

So if we assume that “supernatural” is something that “is always imaginary” then I don’t see what’s wrong with just calling it “imaginary” and being done with it. Actually, that was a bit dishonest: I know exactly what’s wrong with it, and it’s that people who don’t think it’s imaginary appreciate having a term for it that encourages them to pretend that it’s not imaginary. They complain when you call their imaginings “imaginary.” If your view is that we should use the term “supernatural” to make it easier for all involved to understand the mistake they are making, then I’d flip that right around and argue that calling it all “imaginary” is much clearer and easier to understand.

People who believe in the supernatural in some sense believe something fundamental about things that are minds or mindlike. They may well have wrong ideas of what minds are and how they work, but if we understand the mistake they’re making, we can address it directly.

I think we’re actually in agreement, sort of. I’d phrase what you said a bit differently:

People who believe in the supernatural imagine there are things that they have no way of verifying anything about. They may well have wrong ideas of what’s real and what’s not, and we all understand that sometimes telling the difference between reality and our imagination can be very difficult.

If you’re trying to help someone who believes in something “supernatural” to understand their beliefs, you’re eventually going to either have to look at their evidence or explain to them that they’re imagining things. Encouraging them to set up a hypothetical special class of imagined things, only so you can tear it down, is encouraging them to be wrong and encourages them to dig in their heels and defend their mistake because, after all, the “supernatural” is a “thing.”

It seems to me we agree, we’re just not in agreement about the tactics to use when talking to someone whose imagining things that aren’t there.

Actually, I don’t think they really have thought it out that well. It seems to be part of the mistake that they’re making.

In my experience, that’s very true. If you start explaining that, you’re fighting a land war in Asia – they believe there’s something there, and they (obviously, or they wouldn’t believe it) have some kind of evidence that has convinced them that there’s something there. After all, something gave them the idea! So I usually start by asking about “how did you come to have this belief?” but I feel that treating it as if it’s a belief/imaginary doesn’t give as much ground as talking about “supernatural” like it’s a real thing. It is literally not a real thing.

And — in some cases — they might argue that supernatural phenomena do sometimes have those properties. Ghosts or spirits are sometimes visible, sometimes move things, sometimes emit or absorb heat, sometimes cause vibrations in the air that can be heard. That’s kind of the premise of “Ghost Hunters”. They just won’t let you pin them down on how that whole occasional interaction works.

Right.

They believe they are experiencing something. The question is: what? To say we “experience” something means we are having physical stimulation of sensory apparatus that are all based on physical properties of reality in accordance with physical law. If they are “seeing” something, to see it, it has to have all the properties we’d associate with existing. I totally understand that they think they are seeing something. They probably are! In which case they’re making a mistake or they just don’t understand what they are seeing. Because if they were seeing a “being of pure energy” they’d probably be, you know, on fire, or blinded, or something.

So, again, I think we’d be making a strategic error to talk about “beings of pure energy” as anything other than imaginary. Because then we’ve moved into this shaky ground where we’re suddenly arguing about stuff – as you say – they know nothing about, and then they fall back to “I just know what I saw.” We’ve got to come back and say “that’s not how eyeballs work. So, it’s possibly a delusion or a mistake.”

Actually, I think that goes for their belief in God as well. (“God could generate or reflect photons, or move physical stuff, or make vibrations in the air — he just . . . doesn’t want to do it all the time. He wants us to believe even though he doesn’t do those things on demand, only when he feels like it, which is very very rarely. Something something blah blah free will, because God just loves free will. Do you want to be a robot?”) And like that. Again, they will often utterly refuse to even think about how that whole infrequent interaction works, or resort to quantum handwaving.

Yup. I’ve been down that path before and it’s very frustrating for me.

Try asking one of the faithful “how does the hand of god work?” and see how that works for you. Usually you get a bunch of whargarbl.

It’s very silly when you try and think about it. That’s why I try not to engage with it, and to categorize it as “imaginary” unless whoever I’m talking to is able to explain to me why they are convinced it’s not. I’m not dogmatically saying “everything is imaginary” – it’s generally a more gentle enquiry: “why do you believe that?”

Quibble:

Not quite: “everything which is known to be real is also imaginary”.

cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/If_a_tree_falls_in_a_forest

John Morales@#26:

Doesn’t that make it a subset, since there are more imaginary things than there are real things, and (real plus imagined things) are completely overlapped by (all imagined things).

If I made a mistake I apologize, I wasn’t trying to mischaracterize your comment.

Just trying to be strict by acknowledging that there is good reason to believe that not everything that is real has been imagined.

Thus my careful phrasing: “things that are real” vs. “things that are known to be real” — a concession that doesn’t detract from the overall claim.

John Morales@#28:

there is good reason to believe that not everything that is real has been imagined

Ah! I missed that. Yes.

Nobody has imagined that seashell that the whelk left on the beach where nobody has looked. But it’s there. Hm.

I wonder if reality, since it can be subdivided arbitrarily, can be subdivided infinitely. In which case our imaginations and reality are both infinities.

So, that shell, I just mentioned, assuming it’s real: now look at the top half, then the bottom. Next the left side. Top 1/10. Etc.

Thanks.

Anyway, let’s not get into the cardinalities of infinities or Gettier cases. :)