There are still a few spiders hanging around outside. This one was adjacent to the house, where Mary found her hiding under some leaves.

She was cheating, though, because she was living under the dryer vent where it periodically warms up.

There are still a few spiders hanging around outside. This one was adjacent to the house, where Mary found her hiding under some leaves.

She was cheating, though, because she was living under the dryer vent where it periodically warms up.

Winter is a tough time to be an arachnophile, especially in the Great White North. It’s even tougher to be a spider. They’re mostly gone from outdoors — I’ve been looking, and everything is frozen and windy, the bugs are all dead, and it’s no place for an arachnid.

They do have some places to thrive, though: in your house. We people at least provide refugia for a few species, like the theridiidids I’ve been following. My wife, who has the eyes of an eagle, found this tiny little guy in our kitchen and scooped him up. He’s a juvenile so it’s hard to tell, but the palps look swollen and he’ll probably be ready to mate after his next molt.

The photo isn’t the best. A) he’s very smol, b) I’m shooting through plastic, c) he’s dangling on a single slender thread spanning the tube, and is practically vibrating, and d) he’s very excited because I fed him a fly, and he’s fangs-deep in that juicy fresh beast.

He’s Parasteatoda, and has a spectacularly stark pattern of angular pigments on his abdomen (not adequately shown). Once he has settled down and is nestled in a comfortable web — it takes a few days for them to build a cozy nest — I’ll have to get some better shots.

At least when people ask where spiders go in the winter, I have an answer. They go to my house.

I’m buried in paperwork today and have scarcely had time to do anything with the spider colony today, but I did make my usual scan through the adult cages for new egg sacs (nothing today — they’re still all lurking, full of insect goo), and looked through the juveniles to see who I needed to promote to a larger container. Here’s one with a beautiful complex pattern of mottling on her abdomen, so I grabbed a photo just prior to moving. She’s not appreciative of being shuttled around and disturbed, so she’s in her standard “leave me alone” pose.

That’s Parasteatoda, by the way. Beautiful plumage! Lovely plumage! She’s just restin’, really she is.

Now for something totally different. I’m gearing up for a project in which I track the developmental progression of pigmentation in juvenile spiders, and along the way, also map out variation in that pigment. Analyzing all that will require a fair amount of data; I’ll have to do a daily collection of pigmentation images for a single cohort of spiders, and organize those for analysis. I have a poor idea of how much time that will take, so I did a speedrun this morning. I lined up 6 containers of juvenile spiders (all S. triangulosa from the same clutch, plus one S. borealis of roughly the same age), and racked them up for fast photography. I gave myself 30 seconds per spider to get a photo series, which turned out to be easily done, the fastest part of the whole process.

Then I took all the images and made a focus stack, which took a while but since it was all automated was fairly painless. Then I rotated all the images to the same orientation, anterior upwards. First glitch: some of the spiders were annoying and presented a side view to me, rather than the dorsal view I wanted. I went with it anyways; the only way to get them to oblige is to catch them in repose in the appropriate position, so that’s going to take a couple of trials to get right. Next, everything was scaled to the same size.

Data collection: a few minutes. Processing the images: over an hour. I think I’ll be able to automate some of the processing, though, which ought to simplify and speed it up. The end result is a series of standardized images of 6 spiders in which I can see the dorsal pigmentation fairly well, although two of them were not compliant about lying in an optimal position.

Today was a feeding day, and since I’m trying to include some variety in their diet, I gave the spiders mealworms. Nice plump mealworms, conveniently placed directly in their webs.

They all turned up their noses, or what passes for noses, at them. They didn’t exhibit the slightest interest, which was disappointing after their spectacular voraciousness when fed waxworms last week. I don’t know whether it’s that they’re still full, or they just don’t like mealworms, or they’re just being obstreperous. I told them, “If you don’t eat yer meat, you can’t have any pudding. How can you have any pudding if you don’t eat yer meat?” and even that left them cold and uncaring.

So no pudding today, ladies.

All right. One spider is nibbling on the delicious meal I prepared. Gilly gets pudding!

The pudding being served today is Jellied Beetle Grub Guts. I hear it’s very popular in England.

Some people mentioned I should try focus stacking on my spiders, so I fumbled around and found some inexpensive software to do it, and gave it a shot. Here are a couple of trial runs (including some spiders I photographed in a single plane yesterday.

I’m just going to say…nice. Also easy. I always take multiple shots anyway, so I just do what I always do, maybe being a little more careful about centering each shot as identically as I can, and then dumping 4-8 photos into the software. I especially like how the juvenile in the third image turned out, letting me see individual hairs on the legs while not compromising the sharpness of the abdominal pigment pattern.

A few words about how I’m doing this: this is my Spider Studio.

It’s nothing fancy, as you can see. I’ve got a Canon body and a speedlite; I’m using my lovely Tokina macro 100mm lens, with a couple of tube extenders for extra magnification, and there’s also a big white diffuser there. I’ve got a bright LED panel to the left and back, and a simple clamp light with a full spectrum light on a jointed arm.

There are some colored papers on the bench top that I can use for backgrounds, but they don’t matter much with the big adults, who are usually hunkered down in a corner of their cardboard frame. The camera is stationary on a tripod, and I’m doing everything manually, focusing by holding the spider’s container in one hand and moving it back and forth, while in the other hand I’m holding a remote trigger and clicking away madly. The juveniles are contained in these clear plastic boxes, about 5cm square — I just pop off the lid, and there’s plenty of light from all around to illuminate the animal.

Hey, if handheld focus stacking is good enough for Thomas Shahan, it’s good enough for me. I was worried that I was going to need a fancy optical bench and something that would allow me to do precisely calibrated advancement of the camera focus, but nah, it turns out to be far easier than I feared.

I was also concerned because I’d seen all these finicky tutorials about using Photoshop or some other software to prep and align each frame, which was going to be tedious. Nope, don’t need that either: I found a program called Focus Stacker that does automatic alignment and assembles all the images into a single sharp result. It’s totally mindless, which I need: shoot a bunch of images with changing focus, drop them into Focus Stacker, and a few minutes later it presents you with the stacked image. I’m going to do this with all my spider photos from now on!

The spider colony wasn’t very lively today. Everyone is still bloated from that waxworm feast last week, and even when I threw flies right into their webs they wouldn’t move — they just sat there, at best they might waddle a bit and desultorily wave a claw at such mundane fare. They now expect more. I promised them mealworms for tomorrow, but no, this is not enough, they have acquired a taste for larger prey.

“Bring us man-flesh,” they whispered.

I countered by telling them that in their current state, they weren’t going to be able to run down a baby, let alone a college freshman. They waddled towards me and hissed, which wasn’t too scary. They look like barrage balloons with a couple of feebly waving legs underneath. Like this:

Look at that! She’s not in a state to scamper at all. She’s huge.

Also pretty. Parasteatoda has these mottled rings of pigment in shades of black and brown, not at all flashy, but subtle and elegant. With abdomens so distended, they’re easy to admire, too. (by the way, the white circle top right is scrap from a hole punch, so you can estimate the size.)

They’re also marvelously variable. Here’s another Parasteatoda with an abdomen that looks like it was made up as an abstract mosaic. If you stare at it long enough you’ll see patterns. I’ve got my eyes open for one with Jesus’s face.

Right now I’ve got a bunch of full-grown adult females that are mostly immobilized by their gluttony, and then a largeish collection of juveniles in the incubator. I’m hoping to upgrade some of them to the larger cages soon — probably over Christmas break — and then I’ve got to introduce males to these young virgins. The Parasteatoda babies really are babies, tiny little spiderlings, that will take a little longer. Meanwhile, the next generation of Steatotoda triangulosa are coming along.

I’ve also got a few S. borealis, but I’m not sure I want to expand their numbers, since the Parasteatoda and S. triangulosa ought to be enough to keep me busy. On the other hand, S. borealis is so goth, with their blackish-purple bodies and gray racing stripes.

They also grow to a larger size. I may have to keep a few around looking badass.

I found one of my Texas S. triangulosa, Jacinta, in her cage this morning, lying on the floor next to a completely drained and shriveled waxworm, unmoving. I nudged her, and she was lying bloated in a puddle of bodily fluids, dead.

This is not good.

So, like the title asks, can spiders lack self-control to the point that they’ll suck prey dry until they rupture? I may be treading new medical frontiers here.

I have to love speculative science — it’s in my contract as a popularizer — but I also like solid, well-established science and the cautious determination of incremental advances in our knowledge. Looking at both ends of the continuum and everything in between sometimes exposes some very poorly thought-out leaps in people’s assumptions, though, and then it’s also in my contract that I have to be grumpy and point out the flaws. This morning I’m feeling my grumpy side.

Let’s start at the beginning, with some nice work in tardigrades. Tardigrades are cool, obviously, and have a reputation as being tough customers who can survive all kinds of stresses that the environment throws at them. Freeze them, dry them out, throw them in outer space, zap them with radiation, and they can cope…at least, they cope far better than we do. Part of this ability is that they’re small and relatively simple, and being tiny and compact in itself is an advantage, but in addition, their cells have a sophisticated battery of proteins evolved specifically to enable them to handle stressful cellular situations without giving up and dying. It’s a sensible approach to take apart the tardigrade genome and puzzle out the genetic strategies they use to optimize cellular protection from stress, as Kunieda and others have done.

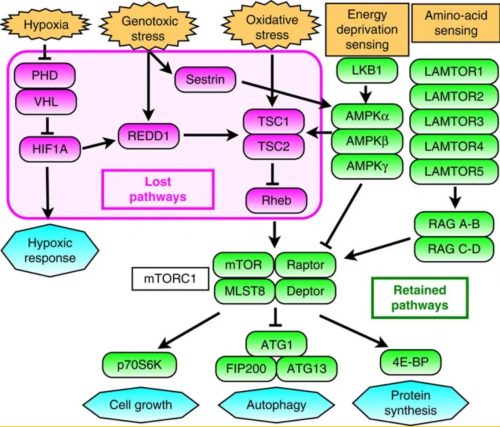

They scanned through the tardigrade genome looking for differences with other, less resilient animals, and found that sometimes that change involved deleting pathways that triggered stress responses. For instance, the genes in purple below are present in us, but missing in tardigrades.

Gene networks involved in the regulation of mTORC1 activity. Magenta indicates genes absent in the tardigrade genome and green indicates retained genes. The interconnected eight genes mediating environmental stress stimuli to downregulate mTORC1 were selectively lost, whereas all components involved in sensing and mediating physiologic demands were present.

This absence makes sense. It is desirable for our cells to kick the bucket when hit hard by environmental stresses; one kind of instance where this could happen is in cancer, where cells are in a poor physiological state, and it’s better for them to die and be replaced by healthy cells. Tardigrades, on the other hand, are already in possession of only a few tens of thousands of cells, and may be trying to cope with a systemic stress that affects every cell in their body, so this approach is not such a good one for them.

They also identified unique genes found only in tardigrades, such as this one, called Dsup, short for damage suppressor. This gene makes a protein that is associated with the DNA, and which has a high affinity for DNA; it’s also expressed in tardigrades with a high resistance to radiation damage. So, the immediate question is…is this protein responsible for radiation protection, and how does it work?

Since tardigrade cells have a lot of mechanisms for dealing with stress, and they want to just look at this one protein, the authors extracted the tardigrade gene and transfected it into a human cell line in order to determine its effects on a cell lacking all the other stuff a tardigrade cell provides.

They chose to use HEK293 cells (HEK is short for human embryonic kidney). A word of caution: these are cancer cells, not normal human cells. They are a popular cell culture choice because they proliferate readily in a dish, and are easily transfected with foreign DNA. They are hypotriploid — having nearly 3 times the number of chromosomes of a normal human cell — and contain adenovirus DNA that has turned them into madly dividing cancer cells. That doesn’t matter for the Kunieda study, though, since they just want to add a tardigrade protein to see what new properties it confers on the cells.

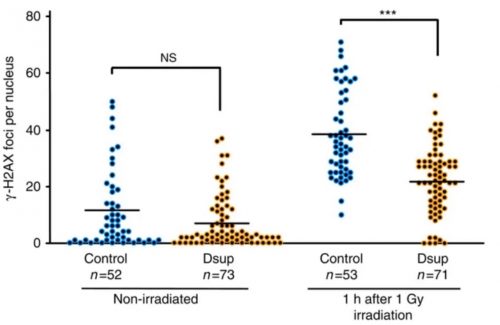

So they hit untreated HEK293 cells and HEK293 cells incorporating the tardigrade Dsup gene with X-rays, and found that the Dsup gene protected the chromosomes — they saw 40% fewer single-strand DNA breaks. They also saw that Dsup reduced the number of double-strand DNA breaks in these cells. They also did good controls, for instance knocking down Dsup expression in transfected cells, and seeing the protection going away.

Distribution of the numbers of γ-H2AX foci per nucleus is shown. Each dot represents an individual nucleus of a HEK293 cell (Control) or a Dsup-expressing cell (Dsup) under non-irradiated and irradiated conditions. ***P<0.001; NS, not significant (Welch’s t-test).

[γ-H2AX looks for phosphorylated histones that form around double-stranded DNA breaks]

Good stuff. Good fundamental cell biology. There’s a lot of work here, but that’s what you have to do to tease out the role of various components of the stress response.

But then it gets weird as it percolates up into the popular press. This was a focused bit of research designed to assess how tardigrades defend themselves against radiation that used a human cell line as a tool, and suddenly, that’s the newsworthy part of the work. It starts with a Nature news article — they should know better, and it does start with a relevant discussion of the work, and then we get the section where it just has to be explained how it could affect humans.

This makes the new paper’s findings “highly interesting for medicine”, says Jönsson. It opens up the possibility of improving the stress resistance of human cells, which could one day benefit people undergoing radiation therapies.

Wait a moment. Just think it through. You, a doctor, have a patient with cancer that you’re going to treat with radiation therapy. Do you really want to make their cells more resistant to radiation? Sure, their healthy cells, but if you’ve got a way to transfect healthy cells with Dsup that does not similarly help cancer cells, you’ve probably got better molecular tools to target cancer cells selectively than radiation anyway.

Then, the line that’s going to spawn a lot of crap, from Kunieda himself.

Kunieda adds that these findings may one day protect workers from radiation in nuclear facilities or possibly help us to grow crops in extreme environments, such as the ones found on Mars.

Oh jeez. This is where Live Science steps in and builds a fantasy of genetically modified humans colonizing Mars.

Will we one day combine tardigrade DNA with our cells to go to Mars?

Chris Mason, a geneticist and associate professor of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell University in New York, has investigated the genetic effects of spaceflight and how humans might overcome these challenges to expand our species farther into the solar system. One of the (strangest) ways that we might protect future astronauts on missions to places like Mars, Mason said, might involve the DNA of tardigrades, tiny micro-animals that can survive the most extreme conditions, even the vacuum of space!

This is what prompted me to dig into this line of research. I read this hypothetical, and my cortex immediately sneezed “Bullshit!” in an acute skeptical reaction, and I had to read further. It’s the combination of an imaginary Mars colony and an imaginary radical re-engineering of the human genome to produce customized genetic humans to labor under conditions of extreme environmental hostility that set me off. None of this is realistic. None of the evidence so far is at all adequate to justify this kind of speculation. There is only the glimmering of consideration for the ethical consequences of such experimentation, if it were even feasible. Is genetically modifying your offspring so they can more efficiently farm potatoes on Mars likely to be something they desire? Hey, though, it’s an opportunity to bamboozle a gullible audience with buzzwords!

One way that scientists could alter future astronauts is through epigenetic engineering, which essentially means that they would “turn on or off” the expression of specific genes, Mason explained.

I detest the casual abuse of the word “epigenetic”. I’m doing “epigenetic engineering” right now — my metabolism undergoes the usual seasonal shifts as we move into winter. You’re doing it too. Cells are constantly going to “turn on or off” the expression of specific genes as an expected consequence of basic biology. It sure sounds sciencey though, doesn’t it?

Alternatively, and even more strangely, these researchers are exploring how to combine the DNA of other species, namely tardigrades, with human cells to make them more resistant to the harmful effects of spaceflight, like radiation.

This wild concept was explored in a 2016 paper, and Mason and his team aim to build upon that research to see if, by using the DNA of ultra-resilient tardigrades, they could protect astronauts from the harmful effects of spaceflight.

This is where I get really irritated. See that phrase, “explored in a 2016 paper“? The “2016 paper” is the Nature news article I cited above. The only “exploring” of the concept is that one line from Kunieda, almost certainly prompted by a journalist prompting him to say something about the relevance of his research to humans, because they don’t understand basic biology.

Then there’s that bizarre claim about building upon tardigrade research to use tardigrade DNA to protect astronauts from radiation. It’s not a quote, so I expect the Live Science journalist just invented it to say some random something to justify the article, but I would just ask a simple question of whoever made it up.

How?

What specifically is being experimented on to improve astronaut’s resistance to radiation?

I’m going to guess that the real answer would be nothing, at least not yet. Let’s keep on eye on those wacky basic biologists who are studying core processes in genetics and cell biology with work on weird organisms that aren’t humans at all, and hope that sometime in decades to come some methods will emerge that will be applicable to human medicine. But until then, nope, nobody is shooting up astronauts with magical tardigrade DNA.

A study of “star” scientists in biology discovers an unsurprising fact: their fields undergo a substantial change when they die.

In the first two years after a star’s death, publications in their subfields increased modestly. But as the years passed, breaking the numbers down by author showed a startling change: Papers by newcomers grew by 8.6 percent annually on average. At the same time, papers published by collaborators took a nosedive, decreasing by about 20 percent a year. After five years, growth from newcomers was so substantial, it made up for the deficit from the collaborators.

In other words, large swaths of these fields had essentially been turned over.

Strangely, the article doesn’t dwell much on the likely cause: funding. It doesn’t even have to be intentional, but reviewers and study sections at the funding agencies tend to be biased by the presence of those who have already been funded, and big labs will have an undue influence because they have so many former students cheerleading for their mentors. This stuff also affects hiring — if you come from a famous lab, you’re more likely to get interviews and jobs.

That’s always been my impression, nice to see the inertia of big-name biologists measured.