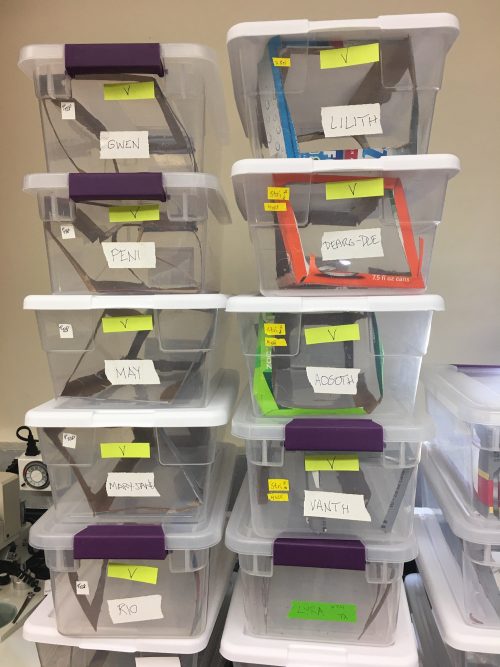

I know you’re in shock that I posted a picture of a bird (what is this blog coming to?), so let’s quickly compensate. I went into the lab this morning to see how the new lab-bred generation is doing, and they were looking great — they had nice webbing everywhere, they had slung some hammocks, and were hanging about looking comfortable, always a good sign. I ambled back to my office, took care of some student stuff, and took my time about getting back to snap a few vacation photos of happy spiders lazing in their new digs. In the time it took me to wander back, Lilith (S. triangulosa, obviously) had up and molted!

This is also a very good sign. The new spiders are getting comfy and growing.