…one should spend some time with one’s spiders. I know it is numerically the 10th month, but it should be the 8th month by name, if not for some silly Romans who tried to squeeze a couple more emperors into the calendar. It was feeding day anyway, so I spent a little time giving them treats in celebration.

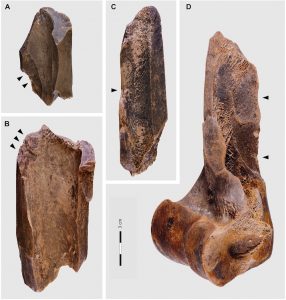

Here’s Blue, who gobbled down her mealworm instantly, and is now dabbling her toes in her water dish.

It’s getting more difficult to photograph Blue, because she’s covering everything with silk — when you look in from the side, it’s a haze of strands everywhere, and I have to remove the lid to the terrarium to lean in and see what she’s up to.

I fed the Steatoda borealis, the Parasteatoda tepidariorum, and the Latrodectus mactans juveniles as well. I’ve isolated about 80 black widow juveniles in individual vials, and am running out of room in the incubator, so there’s about 80-100 more left in a container together, like a giant colony of black widows. It’s a Darwinian world in there — I figure I’ll let the numbers decline and then extract the biggest survivors.

One thing I’ve noticed is that the isolated individuals, in spite of getting a bounty of fruit flies twice a week, are growing more slowly than some of the black widows in the communal container. Most are small, but there’s a few that stand out as growing distinctly larger than their siblings.

(Photos were taken immediately after I dumped a lot of fruit flies into the container, so they’ve all got their faces snout deep in dinner.)

I have to speculate that maybe, just maybe, some of the spiders are eating their siblings.