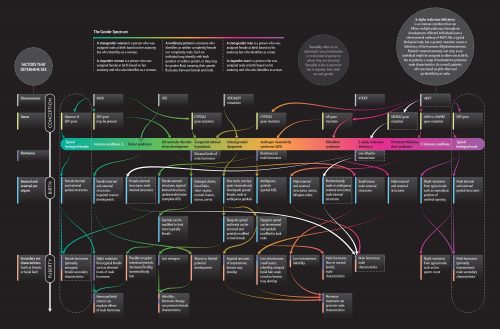

Now will you believe me? I keep saying that sex and sex determination are far more complex than just whether you have the right chromosomes or the right hormones or the right gonads, and now here’s a lovely diagram that illustrates some of the steps in sex determination.

The biology is set up to favor driving an individual to one side or the other, but there are so many detours that can be taken en route that it is ridiculous to ignore all the people who end up following a more unique path.