I hope he enjoys them, because I’m more than a little tired of those obtuse wankers. Rutherford is writing about what makes humans unique, and isn’t shy about pointing out that most of the pop sci claims are nonsense.

Because sex and gender politics are so prominent in our lives, some look to evolution for answers to hard questions about the dynamics between men and women, and the social structures that cause us so much ire. Evolutionary psychologists strain to explain our behaviour today by speculating that it relates to an adaptation to Pleistocene life. Frequently these claims are absurd, such as “women wear blusher on their cheeks because it attracts men by reminding them of ripe fruit”.

Purveyors of this kind of pseudoscience are plenty, and most prominent of the contemporary bunch is the clinical psychologist and guru Jordan Peterson, who in lectures asserts this “fact” about blusher and fruit with absolute certainty. Briefly, issues with that idea are pretty straightforward: most fruit is not red; most skin tones are not white; and crucially, the test for evolutionary success is increased reproductive success. Do we have the slightest blip of data that suggests that women who wear blusher have more children than those who don’t? No, we do not.

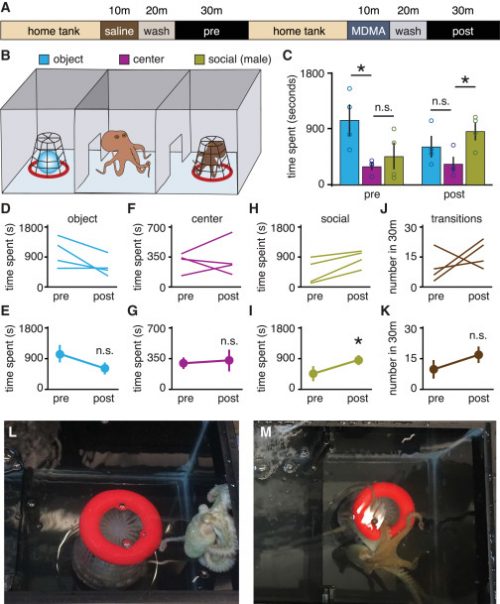

Peterson is also well known for using the existence of patriarchal dominance hierarchies in a non-specific lobster species as supporting evidence for the natural existence of male hierarchies in humans. Why out of all creation choose the lobster? Because it fits with Peterson’s preconceived political narrative. Unfortunately, it’s a crazily poor choice, and woefully researched. Peterson asserts that, as with humans, lobsters have nervous systems that “run on serotonin” – a phrase that carries virtually no scientific meaning – and that as a result “it’s inevitable that there will be continuity in the way that animals and human beings organise their structures”. Lobsters do have serotonin-based reward systems in their nervous systems that in some way correlate with social hierarchies: higher levels of serotonin relate to increased aggression in males, which is part of establishing mate choice when, as Peterson says, “the most desirable females line up and vie for your attention”.

I’m definitely buying his new book, The Book of Humans: 4 Billion Years, 20,000 Genes, and the New Story of How We Became Us when it becomes available in March. I’ve been praising his last book, A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived: The Human Story Retold Through Our Genes, to everyone I know, and I just learned that it’s going to be used as a text in one of the anthropology electives offered at our school. He’s an author you must not miss if you’re interested in good explanations of evolution and genetics.