Everyone has been telling me about this time-lapse video from the Nikon Small World competition. I twitch a bit when I see it. It’s just too familiar, because I used to work on those cells.

Just to orient everyone, that’s an embryonic zebrafish, head to the right, tail to the left, lying sort of upside down with a 3/4 twist, so you’re looking down on the dorsal side and also seeing the left flank of the animal. Does that help?

As you watch it, you’ll initially see two parallel rows of cells located in the dorsal spinal cord — those are called Rohon-Beard cells, and what they’re going to do is a couple of things. They build a longitudinal pathway within the spinal cord so you’ll see they’re all connected by a bright line of labeled nerves running through the spinal cord, from tail tip to hindbrain. They also start sending out peripheral growth cones, building a network of fine axons that cover the animal just beneath the skin. These mediate tactile sensation in the fish.

About a third of the way through, another pathway will become obvious: it’s the lateral line nerve, which starts growing out of a primordium just behind the ear and makes a bright pathway along, in this case, the left side of the fish. I presume there’s another one on the opposite side that we just can’t see.

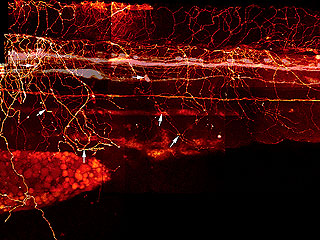

What makes me twitch is that years ago, I tried to figure out how the Rohon-Beard cells make that meshwork. I had a Ph.D. student, Beth Sipple, who collected a lot of data the hard way, by labeling one or a few cells at a time, fixing them, and then trying to reconstruct the interactions from these single cell, single time-point observations to get an idea of how the growth cones were crossing over each other. She also injected dye into that longitudinal pathway to fill a subset of the Rohon-Beard cells and see how their peripheral arbors were organized, as in this image from her thesis.

DiI Labeling of Rohon-Beard and Dorsal Root Ganglia Processes in a 3 d Embryo

Rohon-Beard and DRG processes were labeled by injecting DiI into the DLF and back-filling cell bodies and processes. * indicate the Rohon-Beard dorsal fin processes. Long arrows indicate position of Rohon-Beard cell bodies. Short arrows indicate the position of DRG peripheral processes

It would have been so much easier if we’d been able to just label the whole mess and watch them develop. There’s as much information in this video as there was in hundreds of samples made the old-fashioned way.

This is how we framed it, a few decades ago.

If one looks at the network of Rohon Beard cell sensory arbors once they are well established, the pattern of innervation is quite dense and complex. It is almost as if someone laid a series of irregular nets, one on top of another in random fashion, over the surface of the skin. There appears to be no regular morphological pattern to the arbors individually or as a whole. This is unlike the situation seen in the Comb cell projections of the leech (J. Jellies) which have a distinct shape and a well distributed outgrowth pattern. So how does a Rohon Beard cell arbor (or any developing sensory arbor for that matter) ‘know’ how to grow and branch its dendrites optimally in order to cover an entire receptive field (the skin)? An optimal pattern would arborize over a region such that:

- no point in the field is further than a given distance from a neurite

- no point in the field is excessively innervated

- all regions are equally densely innervated

In other words, each arbor should have a few holes and no clumping regions, as is seen in this image of a Rohon Beard cell arbor at about 23hpf below:

The question I was interested in was how to form a distributed network, with minimal clumping or gaps, and I measured all kinds of lengths and angles and rates and densities to try and figure out how it assembled itself. We inferred a couple of things: that individual axons avoided fasciculating with each other, but that there was no aversion to crossing over each other, and we also inferred that the growth cones had a weak preference for regions of the skin that were not already innervated.

I’m looking at the video and saying, “we were right”, but still wanting to get in there and measure branch angles and trajectories. And also, “oh, man, this technology would have made everything so much simpler.”