My students are also blogging here:

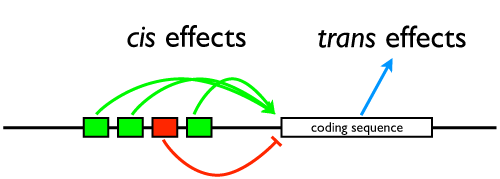

Hard to believe, I know, but this class actually hangs together and has a plan. A while back, we talked about the whole cis vs. trans debate, and on Monday we went through another prolonged exercise in epistatic analysis in which the students wondered why we don’t just do genetic engineering and sequence analysis to figure out how things work, so today we reviewed a primary research paper by Chris Cretekos (pdf) that teased apart the role of one regulatory element to one gene, Prx1, in modifying the length of limbs. It’s a cool paper, you should read it. It’s kind of hard to replicate the teaching experience in a blog post, though, because what I did most of the hour was ask questions and coax the students into explaining methods and figures and charts.

I’m afraid that what you’re going to have to do is apply for admission to UMM, register for classes, and take one of my upper level courses. I always have students read papers direct from the scientific literature, and then I torture them with questions until they extract meaning from them. It’s fun!

Although…it would also be cool to have a scientific-paper reading and analysis session at a conference, now wouldn’t it? Especially if it could be done over beer.