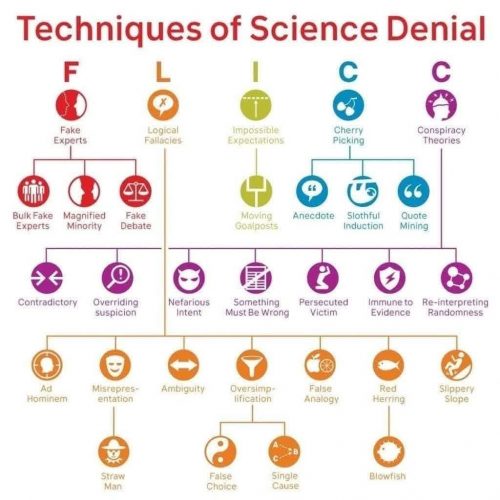

I’m going to be a bit contrarian. Years ago, one phenomenon that was horribly popular among skeptics was the identification and labeling of logical fallacies — it sill is, as far as I know. There’d be a debate, and after the goofball had made his arguments, our side would triumphantly list his Official Fallacies, preferably in Latin, and declare victory. Here’s an example of thorough detailing with nice graphical fillips to give you a feeling of satisfaction as you tear your opponent apart.

I’m not arguing that these aren’t fallacies — they definitely are, and they do invalidate an argument. As a tactic, though, is this effective? You might as well be peppering your opponent with colorful stickers while propping up your ego and reputation with language that comes out of a first year logic course. It all does nothing. I’ve witnessed creationists gushing out a blizzard of logical fallacies — they’re creationists, after all, and they’re defending very silly ideas — emerging unfazed and undefeated, and the audience is never persuaded to abandon their beliefs. They’re right, don’t you know, since God or their incestuous circle of fellow conspiracy theorists agree with them, so who cares if the college boy knows a bunch of fancy words. Anyone who disagrees with us is a Fake Expert with Nefarious Intent and so can be disregarded. Also, the only Latin fallacy they know is ad hominem, and they’re pretty sure that it means strongly disagreeing with me so anyone who thinks the earth is round or that it’s billions of years old or that the climate is changing are guilty of a logical fallacy, too.

It might be satisfying to have a scorecard and tally up errors, but this isn’t a baseball game and there are no referees to award you with victory. These lists of fallacies isolate you from the audience and short-circuit any attempt to make a well-meaning exploration of the deeper reasoning behind bad ideas.

Blowfish fallacy? Not heard of that one before that I can recall..

So what is the recommended alternative, PZ? Ultimately, logic has to be invoked somewhere, because there arguments are also built on logic. It is just that their logic is based on rotten foundations.

Doesn’t that depend on the audience? The type of debate and circumstances of it?

Isn’t a big part of the issue here the general lack of knowledge of critical thinking and how to analyse arguments and understand which ones are valid and which ones’are not on the part of the majority of the public?

Wouldn’t a key remedy for this be better education especially about logic and critical thinking and how to reason and argue more effectively? Always thought that’s something that should be a key topic taught to everyone from early on for socialand national (& even international) gain.

(Off topid – Alwyas thought it would be great if Parlt or Congress sessions were rated and judged by logicians critically tallying up which side is using which fallacies and awarding debate style wins to the side that makes its case best.)

Which audience are we trying to convince here – one that is partisan and willfully ignorant and determined to disagree or an audience outside of that that is more willing to actually consdier the points and cases being made and rationally evaluate them?

So what are the superior alternatives here?

What about cases where one side is totally disingenuous and not well-meaning at all?

The amount of critical thinking skills I was taught between kindergarten and college graduation wasn’t zero but it also wasn’t much more than zero.

A lot of the USA explicitly opposes teaching people critical thinking skills.

I’d never heard of most of these logical fallacies until I dealt with creationists during the early 21st century.

I found them quite useful though.

.1. You learn to see the holes in all sorts of arguments quickly and why they are wrong.

.2. You learn yourself not to commit all those logical fallacies at one time or another.

Three of the most useful are:

.1. Correlation doesn’t prove causation.

I’ve seen senior scientists with multiple grants make that mistake.

This is one of those fallacies that I did learn in college and it has always been useful.

Wikipedia This differs from the fallacy known as post hoc ergo propter hoc (“after this, therefore because of this”),”

Maybe so but they are related ideas.

.2. “That is an assertion without proof or data and may therefore be dismissed without proof or data.” It and you are wrong.

This is Hitchen’s razor and it’s not old enough to have a Latin original.

.3. Sagan, Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof.

Obviously it takes more effort than just identifying and cataloging the logical fallacies, if you want to engage in the argument. You have to present the counter argument with your evidence. I see videos by one blogger who goes to great effort to do that against Christian dogma, particularly Evangelical dogma. However, I doubt he has much impact and he’s probably not changing many minds. So it becomes a personal question whether it’s worth the effort to you.

I think this speaks to a wider problem with the fetishisation of technical terms.

Very often, when I start teaching ancient literature to Latin or Greek classes, I find that a lot of the students make the assumption that giving a technical name to a literary feature is enough to fully explain it. This is an example of prosopopoeia, there’s some litotes, here we have a tricolon, asyndeton and anaphora. It’s almost as if the words are magic spells and they assume a reader will be wowed by the sheer Latinity or Greekness of it all into peaceful quiescence. And these are students who have actually studied the languages – those who haven’t seem even more susceptible to the magic of technical Latin and Greek.

Sometimes I insist my students start out by writing analytical essays without using any technical vocabulary, so they get used to discussing ideas rather than labels.

In my experience, people aren’t persuaded by logic or even (objective) evidence anyway, at least when it comes to stuff that isn’t direct experience. They believe what they believe for emotional reasons: such as to make the world less scary, or to make them feel like they’re worth something, or to fit in, or to justify themselves, to express their anger, etc.

Logical argument doesn’t address the real reasons they believe what they believe.

That chart is poorly organized. If they would switch “F” and “L”, then “L” could have a line going down the left side, and wouldn’t have to interrupt the “C” grouping.

For that matter, the whole thing could be arranged radially, with the major categories near the middle, and the sub-categories at a larger radius.

Why bother? The outcome of the last election has finally convinced me to give up: Our species is too sick and stupid to survive, much less govern itself. We will NEVER have a progressive or equitable society; we won’t even come close. We will forever be governed by the fickle whims of the lowest common denominator, capitalist greed and theistic superstition. There is not point in living. There is no point in trying.

The only thing to hope for is a swift, painless end, but in truth, we’re not even going to get that.

raven @4: Pretty sure Quod gratis asseritur, gratis negatur (what is gratuitously asserted is gratuitously denied) came before Hitchens.

They’ve removed the drinks from a perfectly good drinking game!

Reginald Selkirk @8: In that case you lose the mnemonic “FLICC” (for “fallacy”) across the top. Alas.

This is why creationists love to characterize anything they disagree with as “illogical,” without explaining where the illogic lies. And often it is not the logic, it’s the facts (that they ignore) which is really against them. It’s an example of “saying it first.” They know you will say they are illogical, so they call you illogical first

@3 “So what are the superior alternatives here?” Call them LIARS and hit them with the facts! “Logical” depends on “Factual” anyway, so “Facts First.”

Labelling the specific failures in an already-presented argument is not really about discrediting that already-presented argument. It’s primarily a teaching tool to help prevent similar problems in not-yet-presented arguments.

Consider this argument:

• Indigenous ethnic group X did not independently implement Carnot engines at the same time as did Western Europe.

• Therefore, each member of X is less intelligent than those whose ancestry is exclusively from Western Europe.

I really don’t think I need to label each fallacy in there for anyone reading here to understand that it’s an invalid argument on several dimensions, do I? However, labelling the fallacies is useful in avoiding those fallacies in future arguments (inductively… and that’s yet another argumentation problem!) — after all, the probability that the readers will later have to make and/or evaluate arguments closely approaches 1.

tl;dr The labels are far less reason to disbelieve a particular argument than they are a teaching method for future arguments. (When consistently and accurately applied, that is.)

Honestly, I’ve been saying the same for years.

For sure, learn about fallacies. But you don’t need to name drop them in an argument. Have some self-awareness.

I would argue the point of highlighting the logical fallacies is not to win the argument, because in many/most cases the person making the statements are not arguing in good faith. No amount of discussion, data, evidence, logic will alter their expressed viewpoint. I think the point of highlighting these issues is for the audience that is not familiar with the creationist (or similar) talking points or are open to knowledge, learning, and/or logic.

@raven 4: you write “Correlation doesn’t prove causation”. I have always assumed that people get this wrong because (1) causation should cause correlation; and so (2) correlation is usually a very good place to look for causation. What I have seen in grant proposals is not so much the fallacy, but (2), where a research agenda might be initiated by the discovery of correlations that merit further study. In my own field, Medicine, historically correlations such as cigarette smoking and small cell lung cancer or HIV positive status and the development of AIDS, were important correlations that led to an exploration of possible causal links, and the list of such correlations leading to research on causation is pretty much endless, from a water pump in London to beekeepers and RA.

I expect Creationists to be illogical and use magical thinking. I’m far more dismayed when supposedly skeptical people are oblivious to their own faulty logic.

Case in point, ‘Dear Muslima’ was an exercise in the logical fallacy of relative privation, complete with mansplaining to women that they don’t wear headscarves or hijab, therefore sexism doesn’t exist in Western society. This event had the effect of significantly increasing the sexism in Western societies both online, and in law, and elevating actual rapists to high office. Thanks Dick!

Humans are inherently illogical creatures, which is why we need to make lists of logical fallacies.

Wikipedia includes this fallacy: Courtier’s reply – a criticism is dismissed by claiming that the critic lacks sufficient knowledge, credentials, or training to credibly comment on the subject matter.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_fallacies#Relevance_fallacies)

I’ve gotten by on stating the content of a fallacy directed at the fallacious example, and sometimes even avoiding the name of the fallacy. If they shut down cognitively over the technical language, just speak the logic out.

So someone doesn’t like that newspaper? What’s that got to do with that journalists article? Can I reject all of your sources because I feel bad about a group as a while? (Genetic fallacy).

So they’re saying things in ways you don’t like? Why are they wrong? This is politics, toughen up. (Ad hominem).

I don’t check these to disprove them. I check them to basically say, “This is clear example of X and I am no longer going to discuss it any further. Take that as a win if you want, I no longer care.”

I agree with Akira. The “humanitarian ideal” just isn’t there. We’re barely out of the jungle.

Dennis, Akira is a doomsayer who counsels despair and dismay, and has given up.

(You quite sure you agree with that take? ‘Woe is us!’)

The problem is, if your argument is wrong, it doesn’t mean your idea is wrong (or right…) Only your degree of certainty of belief should be lessened. So pointing out the flaws in arguments to ideas people hold very strongly, means their certainty of belief might just chance from absolutely certain to extremely certain.

And then they make the logical fallacy of thinking that, if their belief is right, their arguments for it must be right, and so you are wrong!

I’m actually not sure if that one is in your chart…

robert79, it’s not that simple.

cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gettier_problem

[also, self-fulfilling beliefs]

John @19: I’ve been accused of the Courtiers’ reply, once on FtB! Someone makes a claim about physics, and it becomes clear they don’t have the necessary background to make that claim. Sometimes the ‘Courtier’s reply’ is the correct one. I do try to avoid it by just explaining why they’re wrong, but they often don’t understand the explanation. Whaddaya gonna do?

[Rob, thing is that PZ gets the credit for it]

@ 22. Dennis K : “I agree with Akira. The “humanitarian ideal” just isn’t there. We’re barely out of the jungle.”

2 million odd years outta the African grasslands / woodlands really?

[interlude]

Jungle!

@29 StevoR – Metaphor. Ever hear of it?

^.. Much less in terms of living in large cities, suburbs and barely over a hundred years since air travel first made theworld much more interconnected and accessible to more people.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the Humanitarian ideal isn’t there or cannot be applied today. It is and can be..

@31. Dennis K Literally yes!

I half agree with Akira and half not. Yes, I think the situation dire and hopeless at least for the foreseeable future, but disagree on what one should do about it.

The world is still here, and we’re still here. Maybe it’s foolish to rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic, but less so to sit on one and look at the stars when all the boats are gone. I recall one of those old pop-culture books on Zen and a story about a man falling off a cliff and grabbing a delicious strawberry. Kind of a cliché perhaps, but it’s true too that unless you think there’s a god at the end of it all who will ask why you weren’t crawling on you bloody knees supplicating, you might as well. If there’s a view, enjoy it and count your luck.

https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fi/uop99576sfn9u2vnda180/iguazu-spider.jpg?rlkey=lf737tcwtro9xmcy36vtne0zg&st=e0l7aq2m&dl=0

Perhaps the poet Zbiginew Herbert had the right idea:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/48501/the-envoy-of-mr-cogito

I first learned the standard fallacies when I took Elementary Logic as a humanities elective, most of a lifetime ago (really, it’s kind of cheating allowing electrical engineering students to take Elementary Logic to fulfill a humanities requirement — half the course was Boolean algebra, but it was given by the philosophy department, so it counted). It’s useful to have these concepts explicitly laid out in your head — an array of tools on your mental pegboard, if you will, to be deployed when you’ve got an argument to take apart (including sanity-checking your own arguments). But some people seem to fetishize them, or act like, having memorized some standard list of fallacies, they’re now ninja critical thinkers. There’s more to it than that.

Somewhat tangentially: I have a hypothesis that many (most/all?) of the identified fallacies should be seen as overzealous application of perfectly respectable and useful reasoning heuristics. Since we were already talking about it, take “Correlation is not causation”: as Hume pointed out, what we subjectively perceive of causation is nothing but correlation. Reliably, A happens, then B happens, ergo A causes B. It’s how humans (and other animals) navigated the world for millions of years. I’m sure you can think of other examples. That’s what makes it so easy to fall into a fallacy: it’s the Evil Twin of some useful commonplace intuition.

[OT]

Matthew, I’m not much for poetry, but Herbert one is an expression of virtue ethics if I ever heard one.

(Hang on to your principles, no?)

[meta]

stevewatson, they’re basically informal fallacies:

“Fallacies are commonly divided into “formal” and “informal”. A formal fallacy is a flaw in the structure of a deductive argument that renders the argument invalid, while an informal fallacy originates in an error in reasoning other than an improper logical form.[5] Arguments containing informal fallacies may be formally valid, but still fallacious.[3]”

(Generally, fallacies of irrelevance)

Language games.

Causation can be defined, and correlation does not match that definition.

(Think of the implication operator in logic; nothing subjective about that)

John Morales @37:

“stevewatson, they’re basically informal fallacies:”

What is “they” referring to, in what I wrote? Please clarify.

But to reply to the point I think you are making: I would include at least some formal fallacies as Evil Twins.

E.g. Reverse Implication:

1) If P then Q

2) Q

C) Therefore P

Formally fallacious, but if P and Q are real world phenomena, and we know that P often causes Q, it becomes a respectable abduction.

The taxonomy to which the OP refers.

That’s why I quantified it as ‘generally’.

Yes.

In order of rigor, deduction, induction, abduction.

(Nice!)

Affirming the consequent. :)

Jim Brady@2–

I think the solution is two-fold. The first is what people are calling “pre-bunking”, that is, educating people on common fallacies and flaws of reasoning so that they can identify them in advance. The reason for this is it is very hard to get people to abandon a fallacy once it has an emotional hold on them. Anti-“pre-bunking”, of course, is the main target of right-wing attacks on education. They don’t want people to understand when they’re being lied to.

The second solution is not to call out fallacies by name but to present the best evidence you can for your position and to explain the main flaws (not every flaw, just the main ones) in any false reasoning, not by naming the fallacy but by showing why the argument is flawed in this case. (Having said that, naming the fallacy can be very effective for an audience that understands the fallacy and is willing to recognise it.)

Neither solution is perfect.

@35–

Causal studies can provide actual evidence of causation. Of course they’re not perfect — the study design can be poor, the cause may be a confounder rather than what the experimenter thinks it is, the inference can be wrong — but it would be perverse to say that the overwhelming evidence of a causal link between, say, spirochaetes and syphilis is nothing more than a strong correlation.

If there is no way of distinguishing causation from correlation, then what would be the point of doing research to distinguish the two?

Please give the full quote in context, with attribution.

“I never met a phor I didn’t like” – Will Rogers

New congressional report: “COVID-19 most likely emerged from a laboratory”

In the near future, the situation in the USA is indeed dire and nearly hopeless.

Societies with 345 million people are like aircraft carriers, meaning they don’t turn very fast or easily. And they reelected some guy they turned out of office 4 years ago for incompetence.

But we haven’t always lost.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, we won a lot. Abortion was legalized, the war in Vietnam ended, Nixon impeached, Johnson didn’t run for office, women were recognized as full US citizens, etc..

Then Reagan. Enough said.

The 1990s with Bill Clinton was another good time. for Progressives and the marginalized majorities of the USA.

Then, our national nightmare of peace and prosperity was ended by electing George Bush who spent 8 years wrecking the USA with a pointless war and the Great Recession.

The last election ended up being a lot closer than we thought. Trump didn’t even get 50% of the vote.

It is always possible that the USA will have another few terms favoring the majority of the population.

As a Boomer though, it might well not be in what remains of my lifetime.

I’m not waiting up for it.

Nope. Nixon resigned before he could be impeached.

Compensating for inadequacy of the status they feel entitled to with anti-intellectualism and xenophobia, expressed through rote sloganeering ingrained by grifty media that eroded away any individual personality they once had and alienated them from peers and family?

Reginald Selkirk@43–

The same process was behind the Cass Report into transgender health.

Causation is just a correlation with thermodynamic irreversibility. :)

@Raven (44):

https://missedstations.tumblr.com/post/766441875994476545/when-people-say-we-have-made-it-through-worse

@John Morales (36):

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there. (W.C.Williams)

Aristotle thought about causes, back in the day.

“Proximate Causes: Immediate causes that directly bring about an effect. For example, striking a match to produce a flame.

Ultimate Causes: The underlying reasons or purposes behind a series of events. For example, the desire to create light as the ultimate reason for striking the match.

Material Cause: The substance or matter from which something is made. For example, the wood and phosphorus in a matchstick.

Formal Cause: The form or essence of something. For example, the shape and structure of the matchstick.

Efficient Cause: The agent or process that brings something into being. For example, the act of striking the match.

Final Cause: The purpose or goal of something. For example, creating a flame to provide light.”

@49 Matthew Currie

Great poem.

I liked it a lot, that about sums it up.

Its important to know and understand the fallacies. To deploy them in a conversation though you need to have ways to make them comprehensible, at the least to the audience if not the person you appear to be talking to.

My favourite example is with the burden of evidence, which creationists try to misconstrue. Sometimes they ask why it matters. My go to is this :

I claim that you owe me $1 million. Provide evidence that you don’t, or pay up.

If you think that I should have to be the one to provide evidence of the debt then you are beginning to understand the burden of evidence.

A summary of the elections of fools and why we have kakistocracies:

“As democracy is perfected, the office of the president represents, more and more closely, the inner soul of the people. We move toward a lofty ideal. On some great and glorious day, the plain folks of the land will reach their heart’s desire at last, and the White House will be adorned by a downright moron.” — H.L. Mencken