Last week, I gave a talk at UNLV titled “A counter-revolutionary history of evo devo”, and I’m afraid I was a little bit heretical. I criticized my favorite discipline. I felt guilty the whole time, but I think it’s a good idea to occasionally step back and think about where we’re going and where we should be going. It’s also part of some rethinking I’ve been doing lately about a more appropriate kind of research I could be doing at my institution, and what I want to be doing in the next ten years. And yes, I want to be doing evo devo, so even though I’m bringing up what I see as shortcomings I still see it as an important field.

I think of myself as primarily a developmental biologist, someone who focuses on processes in embryos and is most interested molecular mechanisms that generate form and physiology. But I’m also into evolution, obviously, and recently have been trying to educate myself on ecology. And this is where the conflicts arise. Historically, there has been a little disaffection between evolution and development, and we can trace it right back to Richard Goldschmidt and the neo-Darwinian synthesis.

There is minimal consideration of development in the synthesis. The big man in the interdisciplinary study of evolution and development at the time of the formulation of the synthesis was Goldschmidt, who actually raised some grand and important issues. He was interested in sex differences; the same genome can give rise to very different forms, male and female. He was interested in metamorphosis; the same genome produces both a caterpillar and an adult moth. And he was interested in phenocopies; the same genome can generate alternative forms under the influence of environmental factors. He had some very speculative ideas about global systemic mutations that haven’t really panned out, and his ideas were tarred with the label “hopeful monsters”, which didn’t help either. It was non-Darwinian! It argued for abrupt transitions! I’ll defer to Gould’s defense of Goldschmidt, though, and would say that those weren’t good reasons to reject some challenging ideas.

The charge that stung, though, was Ernst Mayr’s accusation that Goldschmidt believed that new species could arise by a single fortuitous macromutation in a single individual, that Goldschmidt had abandoned or failed to grasp one of the most essential principles of evolutionary thought: that evolution occurs in populations, not individuals. He did not understand the concept of population thinking. I don’t think he was entirely guilty of that, but I have to concede that there was a disjoint there: as a developmental biologist, Goldschmidt would wonder first and foremost about the kinds of genetic rearrangements that would generate an evolutionary novelty, and just assume that a superior morph would propagate through the population, a process of relatively little interest; while an evolutionary biologist would be less interested in the developmental details of the generation of the phenotype, and much more interested in the mechanics and probabilities of its spread through a population.

Evolutionary biologists and developmental biologists think differently, and that creates a conflict between the evo and the devo. I’m not unique in noting this: Rudy Raff included a table in his book, The Shape of Life, which I’ll reproduce here, with a few modifications of my own.

| Quality | Evolutionary Biologists | Developmental Biologists |

| Causality | Selection | Proximate mechanisms |

| Genes | Source of variation | Directors of function |

| Target | Trans elements (coding sequence) |

Cis elements (regulatory) |

| Variation | Diversity & change | Universality & constancy |

| History | Phylogeny | Cell lineage |

| Time Scale | 101-109 years | 10-1-10-7 years |

|

Modified from Raff, 1996 |

Those different emphases can lead to biases in where we place the importance of various processes. I’ll focus on just two: causality and variation.

When we’re looking at the process of change within our domains, evolutionary biologists have already mastered the art of population thinking: everything is about propagation of patterns of variation within a population. There aren’t explicit mechanisms that generate subtypes to fit the range of roles available. Instead, a cloud of forms is created by chance variation and the unfit are selected out. Developmental biologists, on the other hand, see an organism with a constellation of necessary and dedicated functions — there must be a nervous system to regulate behavior, there must be a gut to process food — and specific molecular mechanisms to programmatically generate them. Embryos do not proliferate a mass of cells with random variants, and then use the ones that secrete digestive enzymes for the gut and the ones that generate electrical impulses for the brain. A lot of development papers really do talk about nothing but proximate sequences of causal interactions that lead to a specific function or fate.

To an evolutionary biologist, variation is the stuff of interest: populations with no variation are not evolving (it’s a good thing such populations don’t exist, or if they do, chance will swiftly change the situation). To your average developmental biologist, variation is noise. It clutters the interpretation of the data. We want to say, “Here is the mechanism that produces this tissue type,” not “Here is the mechanism that sometimes produces this tissue type, in some organisms, sometimes with other mechanisms X, Y, and Z.” We generally love model systems because they allow us to establish an archetype and see a reliable pattern. In the best case, it gives us a solid foundation to work from; in the worst case, we forget altogether that there is more complexity in the natural world than is found in our labs. I would be the first to admit that laboratory zebrafish, for instance, are tremendously weird, inbred, specialized creatures…but they’re still extraordinarily useful for getting clean results.

I will also be quick to admit that the above is a bit of a caricature. Of course many developmental biologists reach out beyond the simplistic reduction of everything to linear, proximate causes. Raff, in that book, goes on to discuss specifically all of the problems of model systems and how they distort our understanding of biology; I could cite researchers like David Kingsley who specifically study variation in natural populations; Ecological Developmental Biology, which describes the interactions between genes and environment; and of course there are all those scientists at marine stations who aren’t staring at tanks full of inbred specimens, but are going out and collecting diverse forms in the wild. I am admitting a bias, but the best of us work hard to overcome it.

And then…we sometimes slip. I highly recommend Sean B. Carroll’s Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo as an excellent introduction to evo devo, I even use it in my developmental biology course. In reducing the discipline to a popular science book, you can see what had to be jettisoned, though, and unfortunately, it’s that whole business of population thinking and environmental influences (clearly, Carroll knows all that stuff, but in distilling evo devo down to the basics, that developmental bias is what emerges most clearly). Here, for instance, is the admittedly sound-bitey one sentence summary of what evo devo is from the book:

The Evo Devo Revolution

“The comparison of developmental genes between species became a new discipline at the interface of embryology and evolutionary biology—evolutionary developmental biology, or ‘Evo Devo’ for short.”

Sean B. Carroll, 2005

Again, this is not a criticism of the book, which does what it does very well, that is, describe the mechanistic process of development and the regulatory logic behind it, but notice the missing words in that abbreviated description: populations and environments don’t really come into play. All we’ve got there (and this is a bit unfair to Carroll) is comparisons of genes between species, which is enough to show common descent and relationships between the phyla, but it doesn’t say how they got that way — which is an unfortunate deficiency for a discipline that is all about how things get that way!

That’s what I’m concerned about. Right now, evo devo is far more devo than evo; we really need to absorb some more lessons from our colleagues in evolutionary biology. A more balanced evo devo would weight variation far more heavily, would be far more interested in diversity within and between populations, and would prioritize plasticity and environmental influences far more. If we did all that, it wouldn’t be a revolution — because it would embrace everything that is already in evolution — but would be what Pigliucci calls the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. What we’d have is a better appreciation of this well-known aphorism:

“Evolution is the control of development by ecology…”

Van Valen, 1973

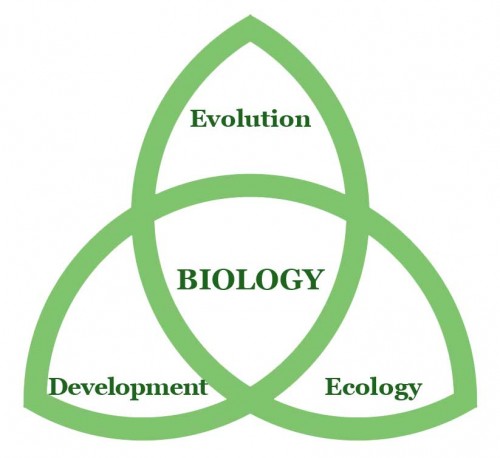

That’s the holy trinity of biology: evolution, ecology, development. Our goal ought to be to bring all three together in one beautiful balance.

(Yeah, I stole the triquetra. We’ll use it far more wisely than the religious.)

(Also on Sb)

This nicely shows why the accusation that reductionism goes nowhere (mainly from religious people, but there are other holists as well) is so wrong. Unification of theories is the ultimate goal (and is what brings eternal fame; it’s not that scientitst are altruistic).

It happens, just not so much in birds.

Interesting reading here, PZ, and I think you are mostly right*. Evo-devo has made good use of phylogeny as a basis for comparison, but (at least to my knowledge) hasn’t examined shifts in variation at a population level.

*And where I am not sure, I am not sure that I’m right either. I’m probably not.

Where in that triquetra does cell chemistry and the internal functioning of bodies fit? I recall substantial portions of my biology classes that I can’t fit into those categories.

Great post (and timely too since I just got into a discussion about reductionism on the tails of this paper, The Fate of Darwinism: Evolution After the Modern Synthesis where there is just a lack of understanding of all the subjects on evolution. It’s like a person criticizing the Atkins diet and then saying “Dieting therefor doesn’t exist”

Nice post. There are parallels with other organismal-to-molecular-level fields like functional morphology and comparative physiology. Variation–among individuals, sexes, sizes, and ages within populations, among populations within species, and among species–is really the only tool we have for studying the evolution of phenotypic function and, I’d now add, its ontogeny.

Well, and a little bit of paleophysiology is also possible.

Cell biology and physiology are subsets of developmental biology.

Obviously.

So, we’re concerned about the development and evolution of evo-devo.

If the ID junk keeps riding on the backs of worthless e-journals, we’re going to have to worry about the ecology of evo-devo as well.

Glen Davidson

Tables need titles.

***

This was very interesting, and it sounds like your emerging research program will be as well.

That was my best guess. Is that literally true of the field, or how the breakdown into these three aspects goes?

I suppose genetics goes there as well. But that’s surely an overlap with evolution. What of ethology? That surely can’t be understood without all three parts.

lowpro: I think your link is borked. Or you are playing a trick on us.

jeez with the ‘triquetra’. It does not encompass the whole of biology. obviously.

Callinectes: Try applying each discipline to the example of sickle cell disease in humans, for instance: a simple human genetic disease resulting from a single point mutation and manifesting in the morphology of a single cell type, said mutation being more prevalent in some subpopulations than others because of an ecological cause – namely a parasite vectored by an insect prevalent in warm, humid environments.

There’s almost a textbook per phrase! ♥

One area that brings these three disciplines together well, albeit at a sub-organismal level, is cancer biology. Given that you said that you were teaching a course in this I did initially wonder if that’s where you might be going. Cancer uses a lot of developmental pathways to achieve growth over which there are variable (all too often incomplete) levels of control. Environment clearly plays a role in terms of triggering mechanisms (chemical, viral and hormonal carcinogenesis being obvious examples) and also of tumor promotion. Tumor ecology and its control is an area where many of the sorts of interactions seen in plant and animal populations (competition, predation, cooperation, mutualism, etc) play out between different cell types. Systems biology and the incorporation of mathematical biologists and their modeling approaches make this a truly fascinating area right now (or would if NCI were given enough funds to support the enterprise). Plus there are some nice model systems out there.

Something that I’m seeing more of is an acknowledgement that we’re(*) not on our own during evolution – see this month’s SciAm article on bacterial mutualism and a posited sexual selection driver based on the mutual attraction of intestinal microfauna. (Paraphrased.)

Yes, co-evolution has been talked about for a while, but mostly in the context of predator/parasite-prey/host or flower-pollinator. I thought this direction was novel & interesting.

I don’t follow biology in depth, so I don’t know what the actual scuttlebutt is in the labs and conferences, but it’s good to see that the internal environment is being considered as well as the external one.

(* Okay, not us as individuals, or humans in general, but the populations out there changing.)

If this is orthogonal or skew to the post, that is because the post is too long and I didn’t read the whole thing …

Nice post Prof. I think that detailed consideration of ecological factors can be particularly fascinating in the context of hominid evo-devo, with wider relevance to linguistics, social and cultural development. For example, we know that areas of the globe with highest biodiversity also have highest linguistic and (at least historically) cultural diversity. How has ecology influenced evolution and development in this regard? It also has huge relevance and opens up exciting possibilities for research into ecosystem function-feedbacks. e.g. how natural selection has influenced the development and resilience of ecosystems and the flow of ecosystem goods and services. Looking at evo-devo in this context (accounting for ecological factors) can have profound implications for the concept of keystone species. Perhaps the most important species in terms of ecosystem function, resistance and resilience are not just those currently seen as (e.g.) ecosystem engineers or those locked into key predator-prey relationships, but those whose evolution and development have influenced the succession and spread of ecosystems (which can include extinct species), or whose genetic diversity is essential to future adaptation and evolution.

The hell, the link IS borked, but it was working during my preview; maybe I truncated the link.

http://www.springerlink.com/content/845x02v03g3t7002/

lowpro: Thanks for the fixed link. I’m going to have to read that back at school tonight. Controversial.

So, did the rebels run, or what?

I love science.

I want to read it but I can’t get that article through my University for some reason =\ usually I can get things from Springer too.

If you can step away from the multicellular organisms, try explaining the life histories of the parasites from an evo-devo perspective.

After having my innocence ruined by the campus art, you expect me to be able to look at a triquetra without seeing…seeing…

Someone put a sheet over it!

Let me first say that this post was awesome! thanks for writing it. Even though I am only an undergraduate student studying evo-devo, I think population thinking can be introduced by the inclusion of genetics into development more thoroughly. When we study variation within the population, we mean genotypic and phenotypic ones, but natural selection for example can’t see the genotypic one, so we must understand phenotypic variation. Which is the noise in development. Also, other evolutionary forces are only understandable from developmental point of view like sprandles. I am not sure if all genetic changes are fully included in developmental biology, like neutral change that doesn’t affect the phenotype at all – it is a form of evolution after all. So it might be a holy square: genetics, development, ecology and evolution. This whole thing is music to my ears, thnx again PZ.

[OT + meta]

CuervodeCuero, I am a native Spanish speaker, so your ‘nym is obvious to me.

lowpro: I got the article, had a few minutes to skim it. I think that it essentially boils down to the statement that insights into development render modern evolutionary theory inadequate. These insights seem to extend from the finding of multiple sources of phenotypic plasticity, developmental canalization, and epigenetic changes.

They seem to differ from Fodor and Piattelli-Palmarini only in the view that “Darwinism” isn’t dead but needs substantial revision.

There is discussion of Kant.

Frankly, this will require more careful scrutiny than I have the mind to give it this evening. Nonetheless, this:

ignores much of the findings of evolutionary-developmental biology and quantitative genetics over the last 15-20 years. Little (or maybe none) of this work is cited, which deals with the evolution and dissembly of major coadapted gene networks, and the fitness consequences thereof.

So far, meh. I’ll give it a deeper read.

Ohhh, just wait ’til Comfort and his cronies/partners in cherry-pickin’ crime get a load of this!!

“Evolution in crisis”

“The science is WRONG”

“See, it’s not settled”

“I like a thick banana in my hand…” (cheap, I know – but iresistable!)

The only parts I got to read other than the abstract came from Christian websites and were cherrypicked lines. My make irk is that they say the current view of the Modern Synthesis cannot answer the question of self organization and life, which it can (thermodynamics helps a lot too -.-) so I’m wondering what they address specifically to come to the conclusion.

The whole of the paper is being taken to say that “evolution cannot answer the complexity of life” or so say the creatards, but I can’t read the paper to tell what it actually says.

It seems to be a sort of “meta-analysis” than anything else.

Considering most mathematical models of evolution involve coding sequence (quasispecies equation) or much more often genes and alleles, it would be interesting to see how regulatory elements work into those models.

Forgive me for a biology dilettante, but what’s the story with laboratory zebrafish?

Variation in development –

I am concerned that there is unmeasured data from the spontaneous abortions that are not seen. If we have a genetic mutation, in a usable final function, it can be stopped in the development stage due to timing problems. But those timing functions are also subject to variation and at some point, the functional form will pop out – does that not put the “hopeful monster” – or at least the “hopeful function” back on the table.

So looking at the failure in development and counting them as a population of function options – but at a much lower frequency.

That would be something to measure

“I’m hot for teacher.”

Van Halen, 1984

golkarian:is there any reason that regulatory elements couldn’t be represented in standard allelic models?

Thanks, PZ! I’m a lurker, for the most part, but let me speak up and say that I really love it when you write about the science that you’re involved with, or even just thinking about. You crack me up with your occasional rants and political peeves, but I’m a lover of science and I love to learn. I learned more from this post this morning than I do on an average day, so please keep it coming, when you are so inclined. (I trust that you won’t let up on the fundies either.)

Have you checked the scienceblogs version? that’s content specific to the more sciency stuff.

I have had the suspicion that population models of complex quantitative traits were fairly well-established by the 1980s, although I don’t remember much* about the particulars of these models. However, they do exist, as my handy Hartl and Clark Principles of Population Genetics explains in an entire chapter. The math at first blush appears hairy. I don’t know if I will have an opportunity to look at this anytime soon.

*F me. Anything.

For those looking for more science and less politics, see the original Pharyngula, which continues here:

http://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/

The version of Pharyngula that you’re enjoying at freethoughtblogs.com was spun off for the benefit of readers who are more interested in skepticism than in biology.

“The problem with evo devo” was posted on both sites.

Development show up much later in biology, than ecology and evolution, no?

Synfandel: Hence the link following the OP.

Everything posted on the ScienceBlogs version is also posted here – but that doesn’t include the comments!

Nah, just legends. “Table 1: Comparison of evo and devo.”

All those places are rather impenetrable and fragmented geographically. They lack wide open spaces – they’re not deserts, savannas or tundras – and they aren’t otherwise uniform like a boreal or temperate forest (temperate rainforests excepted).

Most parasites are multicellular, unless you count all the pathogenic bacteria with their entirely unremarkable life histories.

Good post. Thanks.

I’d call that a title (or a legend – no big distinction). Yours wouldn’t be specific enough, I don’t think.

@David Marjanović #38

Hi David. I’m not sure what your general message there is, but you’re wrong on these points. Biodiversity hostposts that coincide with cultural and linguistic diversity (at least historically) include massive contiguous ecosystems, and have included vast grasslands (the epitome of wide open spaces such as America’s Great Plains and the Caucasian Savannas), deserts (such as Chile’s Atacama and much of the Horn of Africa), expansive temperate forests (such as in the California Floristic Province, South Africa’s Maputaland temperate forests and Mexico’s Madreana Pine Woods), and alpine / montane tundra or scrubland or desert (such as in the Himalayas, Central and East Asian Mountains, Eastern Afromontane Region and the Levant). Many of these are definitely not impenetrable (even the “impemetrable” areas of the Amazon and Central African forests are full of multiple ethnic groups and language clades, and we know from recent evidence that the majority of the Amazon was once under human settlement). Most are uniform (i.e. not fragmented) but heterogenous (i.e. ecologically diverse) because they cover such vast geographic and geological (and climatic) areas.

These areas are high not only in biological endemism, but in cultural endemism and linguistic diversity. The link between biodiversity and cutlural evolution is pretty well established, and is a hugely important factor in assessments of hominid evolution and dispersal.

A colleague has just pointed out to me that the evidence for links between biodiversity and cultural evolution is strong enough that the UN Convention on Biological Diversity considers cultural and linguistic diversity to actually be a part of biological diversity. Which, for me, makes the whole evo-eco-devo thing even more intriguing, as it feeds into international policy on the environment, economics and social welfare.

When the table itself explains enough, there’s no need to repeat what it says.

Ah. Maybe my implied definition of “hotspot” was too restrictive.

By “Caucasian Savannas”, do you mean the Eurasian steppe???

Shouldn’t these be described as widely separated microhabitats?

Yes, and I tried to said so. They have a common cause: when neither humans nor other organisms can easily and quickly move across the whole expanse, they start to differentiate regionally. (Or vertically in a forest or a mountain range.)

Hi David (#43),

No, the Eurasian Steppe includes some of the Caucasus Steppe but is much more massive and extends across Mongolia and into China. The Caucasian Savannas are limited to the Caucasus.

Oh holy baby Jebus no! Microhabitats? No no no. Microhabitats are relatively small (or tiny) niches within larger monotypic habitats in which particular organisms are found. Like a leaf pile is a microhabitat for certain collembola within a deciduous woodland. Biodiversity hotspots are often massive, and typically include mosaics of several habitats and ecosystems which may or may not be connected to various degrees. Separation of habitats is not a defining factor. The Atacama desert is a massive desert ecosystem, unfragmented over perhaps 40,000 sqare miles.

Well, yes sometimes, but mostly no. Evolution is not dependent on an inability to move quickly or easily across a whole expanse (of whatever) (look at the classic example of Larus gull species evolution in the Arctic Circle – 7 or 8 species which have evolved within a defined region, and which travel long distances and interact). Species isolation, confinement and inability to disperse tends to lead to extinction more often than evolution, due to inbreeding, higher vulnerability to disease, reduced resilience to climatic stresses etc. Sure, locally it can also lead to relatively higher rates of mutation (also perhaps through inbreeding, stress etc) but within a hotpost this is not a driving factor for the evolution of diversity, since isolation and niche-forming are not necessarily limiting.

The reasons for the evolution of high biodiversity are not fully understood. But in terms of hominid evolution, particularly cultural development in Homo sapiens and probably H. neanderthalensis, the “cause” of cultural diversity is directly linked to the diversity of living resources (and so usually only proximately linked to the cause of that biodiversity). Look at the Great Plains – hardly a restrictive physical environment, but one that was easily traversed by communities, and which still saw the development of literally dozens of language familes, with perhaps 100 distinct dialects, ethnically discrete customs and art forms etc. Its the same with the Niger-Congo linguistic region in Africa – almost 1,000 languages in a narrow strip that includes the Guinea Forest hotspot, and in which movement is not restricted (many communities interact by travelling along the coast as well as through woodland).

A defining factor in cultural evolution is that many languages have their roots in the development of vocabulary to describe species, seasonal variation and landscape features which were frequently encountered or utilised. The more species, habitats and ecosystems that a community encountered, and in particular the greater the diversity of critical (and culturally significant) living resources, the greater the diversity of linguistic roots (e.g. primary lexical units). When communities settled (voluntary isolation, not necessarily enforced by the landscape) then different language families and local dialects developed.

It might be more self-explanatory to people in these fields, perhaps, but this is a blog post. Your suggestion merely states that it’s a comparison, but there are many bases for comparison. (It’s clear from the table that it’s a comparison, so your suggested title would just restate the obvious.) A title should be more descriptive about what’s being compared – “The Different Emphases of Evolutionary and Developmental Biologists” or “How Evolutionary Biologists and Developmental Biologists Approach…” – with possibly a few more descriptive words within the table itself. The information in tables is condensed, but the reader can and should still be guided through it as well as possible.

21-word, descriptive title.