This post was inspired and cobbled together from an internet comment that accidentally grew into a novel. I’ve attempted to include citations where possible, but the majority of this information comes from working in adoption services research at the Fabulous Unspecified Internship last year and is not easily accessible for citation. Add salt as necessary.

That being said, I’m not an adoption counselor (or any kind of counselor, actually). I’m also not a lawyer, a parent, or a zebra. What I have done is work and research in this field. I am slightly more qualified than your average zebra, but this is not medical, familial, psychological, or lion-avoidance advice.

As a second note, it’s worth saying that I like adoption! I am not discouraging it as an institution or way of having children! I am significantly more likely to adopt than have non-adopted children. There’s a reason the Fabulous Unspecified Internship was amazing, and much of it had to do with working in adoption services. What I am opposed to is telling people to adopt with very bad arguments and misinformation. And one I hear slung about is that of All The Babies Waiting To Be Adopted. (It’s lesser cousin, You’ll Have To Wait A Million Years For A Baby To Adopt is rarer*, and worth it’s own post.)

I’ve heard both arguments–there are hundreds of babies out there waiting to be adopted! and you could be waiting years for a child! The former seems to be the go-to for guilt-tripping people who want to have their own children, the latter for sighing in disapproval at the people who do decide to adopt. And I would like us to stop guilt-tripping people for having their own children.

While less complicated than say, designing a literal Stork Delivery System, adoption is somewhat more complicated than deciding you want a baby and then walking home with a small human. This has something to do with a confusion of language–we call all sorts of ways of getting legal custody over a child that you didn’t contribute genetic material to ‘adoption’.

1. Uncle Joe and Aunt Jane legally adopt Abusive Niece Sally’s son, not wanting him to end up in the foster system? Adoption.

2. Sarah and Jeremy are infertile. They find out about a daughter of a family friend who’s going to have a baby but wants to put it up for adoption and set up a legally binding agreement through a lawyer to adopt that baby. Also adoption.

3. What about Bethany and Emily, who go to an agency, answer lots of questions about their lives, get put on a waiting list, and adopt Baby Andrew a year later? Adoption.

4. Nicole and Noah foster a number of children. They are able to make a ‘forever home’ with one of them–Jason. You guessed it…that’s also adoption.

[What you are experiencing now is semantic satiation.]

When people encourage adoption, or talk about all the babies out there waiting for homes, they seem to be thinking about the experience of #3, with the numbers of #4, and a poor understanding of all. (For the sake of sanity and manageable sentences, we’re going to call #3 ‘adoption’ and #4 ‘foster-adoption’.) They seem to be expecting that there are lots of children who are up for the take-home-forever adoption, in a way that is experientially equivalent to having your own kids: they won’t look like you, but that’s about the only difference, yeah?

Not….really. I’d even venture to say not…at all, and those differences are what make me extraordinarily wary of pressing people who aren’t already eager to adopt to do so.

Foster adoption (#4) is geared towards getting the child back to relatives. That is, the approach is not to locate a new family, but to place the child in a stable situation while their current family stabilizes, or an extended family member can be located. If, and usually only if this doesn’t work out, they’re placed with a new adoptive family.** So, sure, there’s LOTS of kids, and it would be lovely to see them placed in homes that were stable. But you’re effectively telling parents to attach to children they cannot expect to keep, over and over, in the hopes that they someday, will get to keep a child. That’s not a thing many people can or should be expected to cope with. Not to mention, I only want people who can do what it takes to be a good foster parent emotionally doing it.

So what of not-foster adoption?

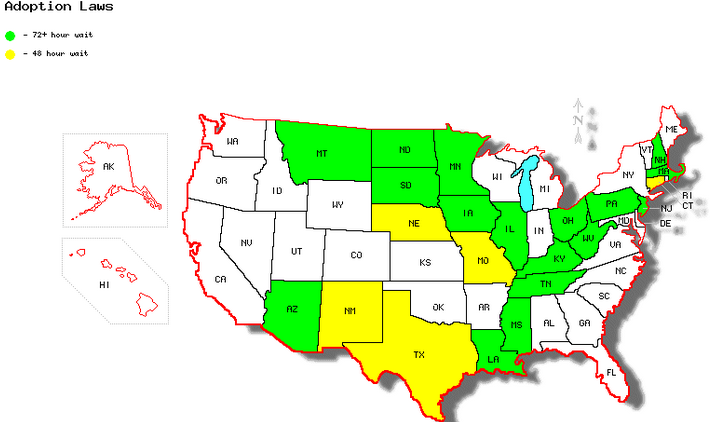

Well, there just aren’t bunches of babies waiting around to be adopted, as evidence by standard wait times. (In the link, time is measure post-portfolio creation, meaning that you’ve interviewed with the agency, gone to training, gotten references, been approved and processed, and created a portfolio, all before the clock was started.)

Adopted healthy-at-birth children, just like nonadopted healthy-at-birth children, can go on to develop mental or physical issues not known at birth. However, parents of nonadopted children might know of the issues in advance–inherited conditions and the like, or because Aunt Jane and Cousin Sally didn’t walk until much later, so no worries when Child Sarah’s motor skills lag a little. Whether or not the parents should be concerned, whether or not Cousin Sally’s delay in walking has anything to do with Child Sarah’s delay, there’s a reference point, and probably an expectation that we, Healthy Parents, were fine, so our child will be!

In fact, I’m willing to bet that this mechanism is partially why adopted children are twice as likely to have contact with a mental health professional. Uncertainty and what if we missed something, and what if this is indicative of problems later and a dash of hyperawareness, combined with on-average higher incomes/class status, and you have greater chances that James’s minor issue will merit getting things checked with your local psychiatrist/psychologist/occupational therapist/etc. But also, referring to that same study–plain English writeup here–adopted children are more likely to end up with a set of disorders called ‘externalizing‘ and are extraordinarily overrepresented in psychiatric care. Friends who have worked in the field confirmed that this was common knowledge.

This is something agencies prepare parents for, of course, but saying to parents “you should adopt a child, who’s at higher risk for issues you aren’t prepared for, and haven’t necessarily seen play out in your own family, and you should do this instead of having a child because there are children who can be adopted” seems incredibly dangerous–those children are suddenly at risk of abuse from overwhelmed parents. (Yes, we should definitely better prepare parents and people at large to interact with people with disabilities. I am 100 percent on board with this! However, given the condition of people’s attitudes and behavior towards disabilities as well as a general wariness at using children as pawns and teaching tools, adopt children! seems like a Very Bad Solution to ableism.)

A note on international adoption: Adoption of children from outside the US is really limited, actually. If you want a closely regulated adoption through the Hague (you want this, this means less chance of false/missing information about the child), there are few countries, and they’re generally closed to you if you’re not young, married, straight, and have no health problems.

Advocate for adoptees! Advocate for less ableism! Create better and more effective treatments for infertility! Improve the foster system! But please stop being inaccurate and guilt-tripping parents who prefer to have children the ‘traditional’ way.

*It’s likely that it’s just rarer in my social circle. In fact, since I started writing this post, it’s become more common.

**Somewhat oversimplified, because bureaucracy.

Other notes:

(1)As a general reference, studies of children adopted after 1990 are more representative than those of children adopted earlier than 1990. Open adoption became the standard practice unevenly, but so far as I can tell, by 1990, everybody figured out that not keeping big secrets and doing a dramatic reveal that radically changes your child’s sense of belonging is usually a better plan.