The pitch of a note is determined by its frequency, and frequency can vary within a continuous spectrum. And yet, in the western music tradition, we only use frequencies with discrete values. That’s not a bad thing, but it implies a whole world of possibilities not explored. Microtonal music, also known as xenharmonic music, sets out to make use of the unused frequencies.

I recently tried listening to a lot of microtonal music, because I discovered that you can find lots of it through the microtonal tag on Bandcamp. Sure, a lot of it isn’t very good because anyone can put music on Bandcamp, but there were enough gems that I continued to peruse the tag. I’ll share just two examples. First, I selected Brendan Byrnes, because I think his music has the most pop appeal, while also being unapologetically microtonal.

I showed Brendan Byrnes to a few people, and some of them couldn’t tell that he was making use of microtonal frequencies at all. It seems fairly obvious to me, because I have enough ear training to tell when a note is out of tune (even if I can’t identify the note). But not everyone has that ability. So for my second example, I tried picking something that was so in your face, that it would be hard to miss even if you don’t have any musical training. I present Cryptic Ruse:

These two examples are from the psych-pop and prog-metal genres respectively. In looking for microtonal music, I very quickly learned that you can combine it with any genre. There’s microtonal folk, microtonal classical, microtonal hip hop, microtonal punk, microtonal psychedelic rock, microtonal drone, microtonal black metal, and so on. Of course, the most common genre tends to be electronic, because it’s easy to make electronic sounds of any frequency, while most other instruments would have to be specially customized.

If you’d like to find other examples, I also suggest The Mercury Tree, Sevish, ILEVENS, ZIA, and King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard.

Theory

I don’t want to emphasize the theory of microtonal music too much, because you don’t really need to understand it to enjoy it. Nonetheless, some basic understanding helps us appreciate it more. Also, I like talking about math if you haven’t noticed.

Listening to music is a bit like staring down a cemetery with perfectly aligned gravestones:

Source: Wikipedia

Patterns emerge: along certain directions, gravestones seem to line up. The directions where they line up are related to rational numbers, and so it is with music. Certain pitches seem to line up because the ratio between their frequencies is close to a rational number. Technically every number is close to a rational number, but we care most about the rational numbers with small numerators and denominators (e.g. 2/1, 3/2, 4/3, 5/4, 6/5, and 5/3). Typically, the smaller the denominator, the more consonant the pitches sound together, and the higher the denominator, the more dissonant the pitches sound together.

That is a bit of a simplification. There are objective ways to measure consonance and dissonance (see this paper or that one), and it doesn’t just depend on the denominator, but I won’t bore you with the details. Note that “dissonant” is not the same as “bad”, and basically all music relies on some degree of dissonance.

Since our tuning system is based on pitches that are evenly spaced from one another, you might think hitting rational numbers is easy. But in fact, our musical system is based on pitches that are evenly spaced on a log scale. Our system takes an octave (the ratio 2/1), and divides it into 12 equal parts. This tuning system gets very close to the all-important 3/2 ratio, and most people can’t even hear a difference that small. But it’s not quite there.

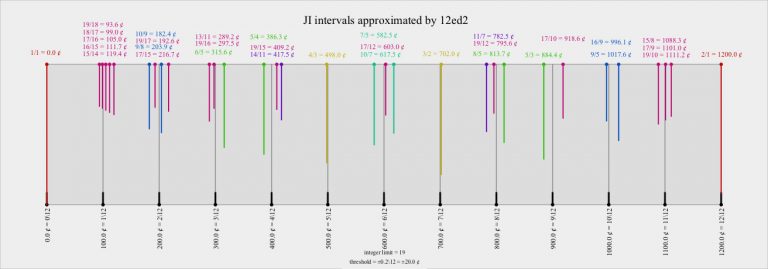

The colored lines at the top show perfect ratios, with the length of the line roughly indicating how consonant the ratio is. Black lines at the bottom indicate standard (12EDO) tuning. Everything is plotted on a log scale. Image taken from a longer article by Dave Tremblay, who adapted it from the xenharmonic wiki (where the text should be more legible).

In microtonal music, there are two common ways to select an alternative tuning system. One way is called “just intonation”–simply select the ratios you want, and play them exactly. This is the method used in the Brendan Byrnes example. The other way is called “equal divisions of the octave” or EDO. The standard tuning system is 12 EDO, but microtonal artists use other tunings like 19 EDO, 22 EDO, 24 EDO, and so on. The Cryptic Ruse example uses 15 EDO.

There are also more exotic systems, and if you’d like to learn more, I recommend 12tone on youtube, who really likes talking about it.

Finding microtonality everywhere

One possible response to all this, is that so-called “microtonal” music is really about westerners rediscovering musical possibilities that have been used in musical traditions everywhere in the world since ancient times. And yes, that’s precisely what it is. No getting around that.

But one of the most interesting things I learned from all this, is that among the world traditions that use microtonality… one of them is the American musical tradition! Specifically, blues has a tradition of “blue notes”, which are in between the pitches used in a standard tuning system. Note that both rock and jazz were derived from blues, and blues derived from African American traditions. Microtonality continues to be used in popular music today, most often by vocalists, although we don’t often talk about it.

So I was thinking back to one of my old favorites, Pyramid Song by Radiohead. I used to wonder what the high note at the 0:31 mark was, whether it was G sharp or G natural. And after my exploration into microtonal music, I came to a quiet realization: it’s neither. I’ve been listening to, and loving microtonality for a long time without realizing it.

You get quarter tones in middle eastern music.

Ah, maybe this is why I love a lot of Indian classical music.

robertbaden @1: I’d never thought about it, but apparently so did Ginastera, Penderecki, and other 20th century Western composers I’ve heard and (sort of, sometimes) liked.

I don’t know anything about this stuff, but I’m guessing that traditional Balkan music might do that too. Like this, maybe?

@Rob Grigjanis

The Shruti system looks very interesting. It looks like a just intonation system with frequent use of the Pythagorean comma (3^12/2^19), a ratio that gets tempered out in 12EDO. I’d be interested in listening to some of that.

I like it.

I’m not sure I would have identified it as microtonal if I hadn’t seen the title of the post though. Perhaps I’m more used to dissonance (I mostly listen to, and play, jazz, including a lot of “weird” sounding stuff. The “blue note” in jazz can be seen as slightly microtonal) I’m hearing this mostly as some recognisable chord progressions with some weird sounding variations on top.

“But in fact, our musical system is based on pitches that are evenly spaced on a log scale.”

This is only a ‘recent’ invention. The first logarithmic table was made around 1600, but their incorporation as a musical scale came MUCH later. Bach used a rational based scale, and played around a lot with the different sounds different bases would have. (In a logarithmic scale, a C major and a D major sound the same, scaled up, unless you have absolutely perfect pitch. Most people have relative pitch, they only hear intervals, not absolute frequencies. In a non logarithmic scale, C major and D major would sound different.)

In fact, even now, most non-electronic instruments have rational scales due to the constraints of physics. A trumpet without its keys pressed can only play frequencies which are integer multiples of its base resonant frequency, as a result it’s effectively tuned in a rational scale. (One can play around with embouchure a bit…) This is why a Bb-tuned trumpet sounds a bit different than a C-tuned trumpet.

Siggy:

Well, you might say there are two options: EDO or not EDO. Those are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive, but “just intonation” is not the right term for failing to be an EDO system. In other words, if you pick any real numbers for your frequencies which don’t divide the octave evenly, it should be clear that this will not always be just intonation.

Also, technically, the specific system we’d call “just intontation” could itself be implemented in multiple ways. What tends to happen is that it’s sort of a starting point, which will then be “corrected” in various ways, to derive something slightly different. (And without modifying, one could use only a subset, for example). That said, the standard thing to do is still to treat it like one thing, so don’t worry too much about what I just said.

Robert79 @5,

I’m sure that our musical background greatly affects our subjective perception of the consonance/dissonance. I have some classical training, so the 5/4 ratio sounds slightly out of tune to me, despite being more consonant (in an objective sense) than 12EDO’s major third.

consciousness razor @6,

I wasn’t trying to exhaustively list every possible tuning system, just the common ones. There are also a few common ones that are neither EDO nor just intonation–for example, the Bohlen-Pierce scale uses equal divisions of 3/1. ZIA has some examples of that. This is all a bit abstract to me though, because I can’t identify any of these tuning systems by ear, except 12EDO and 24EDO.

No, not really. Something like “an attempt at 12-EDO” was already in fairly wide use before that time, more in the range of 1400-1500 I guess. (N.B. I couldn’t say much about places outside Europe, so this is all I’m referring to…. China might have been an early adopter, as it so often was.)

Not everybody used it (some still don’t, obviously), but the idea of spacing the 12 notes evenly was definitely not new. In some sense it had just been assumed all along, until some of their more adventurous harmonic experiments began to expose the issue. They couldn’t precisely calculate 2^(1/12) of course — that’s also not what musicians today ever do either, it should be noted, except implicitly when using electronic tuners. But it’s not hard to devise more practical ways of approximating the same thing, to allow for playing in twelve different keys essentially (without having to retune your instrument). And that’s basically what a lot of people did.

Right, well, Pythagorean and meantone would be the next most common ones, if we’re talking about whole systems.

It’s also very common for vocalists in particular to use arbitrarily “out-of-tune” notes (as in Pyramid Song), which aren’t in anything like a system…. There are some other less drastic modifications, like a “blue third” you’d find in blues music. It’s a lowered major third, almost like substituting with an element from 24-EDO (aka quarter tones); but it doesn’t need to be exactly halfway between the diatonic major and minor thirds. (Same thing may happen with the seventh scale degree, as well as the fifth.) This is very common, but of course the rest of the system is basically unchanged, with only small alterations in select places.

Rob Grigjanis:

I’ve run into them with music for an Armenian duduk.

I don’t know how seriously to take this, but it seems like there’s sort of a divide in the microtonal world (perhaps the music world more generally), between what I’ll describe as “liberal” attitudes/goals versus “conservative” ones. The political labels here are just meant to be evocative … I don’t know how well they’d correlate with their musical counterparts, although the thought processes do seem similar/related, hence why I’m using them for lack of a better set of terms.

On the one hand, conservatives want to bring things back to the good old days. We’ve strayed somehow from the true path. Pythagoras (or some other figure) had it right. He knew the deep mysteries of harmony. There are small rational numbers which have something to do with “what sounds good” to human beings. And so forth. Sometimes such people delve into all sorts of woo: numerology, esoteric mysticism, and the like. But aside from that, it’s not all completely unreasonable. There definitely are physical and psychological/sociological reasons why certain things sound good, as well as social/cultural ones … it just should be taken as a given that science ought to confirm what people had historically/traditionally believed all along.

The liberal isn’t necessarily engaged in that kind of thinking at all. They’re very open to new experiences. And microtonal stuff is one way to get variety, diversity, entirely new realms of music to explore, etc. You spice things up by adding more/different notes. Let a thousand flowers bloom. Don’t let the man get you down. Make your own path. Think different (but don’t buy an Apple). Be free. And so on.

The types of music they’ll make, and the reasons underlying their musical choices, are very different. There are “conservatives” who just want to do stuff like historically-informed performances of medieval music. They’re not about breaking new ground, and that’s not what microtonality is for, as far as they’re concerned. It’s more about growing the perfect ingredient to make the perfect meal, as God intended it, so to speak. The “liberals” are doing something else: microtonality is for making something genuinely new that doesn’t fit into the traditional establishment mold (which is taken to be 12-EDO, common practice tonality, or something along those lines).

correction:

“it just should not [I claim] be taken as a given that science ought to confirm what people had historically/traditionally believed all along.”

consciousness razor @11,

When I took a look at the xenharmonic alliance on Facebook, there were some fairly noticeable divisions, often manifesting as disagreements between people who like just intonation, and people who like EDO. I was rather surprised by this, because I would have thought in a xenharmonic community, those arguments would very quickly get old and played-out, and everyone would learn to live with the fact that different people have different aesthetic preferences.

But I’m not sure that the division I saw was necessarily the same as what you’re talking about. The xenharmonic alliance is mostly made up of creators who want to create something new–so more on the “liberal” side as you’ve described it. I’m not sure how likely “conservative” microtonal creators are to even join that sort of community. But I’m just speculating–it’s fairly hard to read a culture by just looking at a few facebook posts.

In the microtonal tag on Bandcamp, there appear to be several distinct philosophies on microtonality, not always on the axis you describe. But I’ve seen a few artists that go heavy on the mysticism.

Obviously I’m more on the liberal end; I’m interested in microtonal music for the new possibilities that it explores (even if those possibilities are only new to me). And I’m more interested in the expanded pallet of dissonance, than in the expanded pallet of consonance.

Sure, they probably do tend to move in different circles, online and offline. I’ve got a standard academic background in classical and jazz. That means formally studying music theories (plural!), history, traditions in other times/places … the whole shebang.

That by itself puts a person in certain social settings and groups, not much like the ones that converge around bands that would fit into various “pop” genres (including rock, metal, country, rap, electronica, you name it). It’s hard to characterize in a totally satisfactory way, but many don’t read music, don’t study it systematically or extensively, don’t use the same practices, etc. You meet up with some friends in your garage and start thrashing away on your guitar — that’s the picture. It’s not a thing you’re doing at university, and you’re not making connections with various people/institutions there. And it wouldn’t surprise me if you join different facebook groups too.

So, yeah, the “conservatives” are probably more concentrated in academia. But even beyond that, there is a tendency for people in general to give Pythagoras and co. a sort of quasi-mythic status, as if they proved a whole lot of things, with a whole lot of physical/psychological implications, that in fact they didn’t even come close to proving. Or if it may not be Pythagoras explicitly, but they think that the proper theoretical building blocks are the supposedly “consonant” intervals like “pure” third or fifths, as compared to “dissonant” ones. And then it devolves into something like a Sunday school lesson about “happy” sounds and “sad” sounds….. You might have these kinds of thoughts, no matter what sort of music you make. It’s far too simplistic, but it also takes a fair amount of sophistication to understand how this becomes problematic and how to break away from it.

Anyway, I guess it’s (partly) because of how music is usually taught to young children and/or beginners. Scales and triads and tonality are baked in right from the beginning, because nursery rhymes and folk songs and such will be easy to play/sing. You can quickly start to develop technical skills related to reading and performing and so on, without having a clear idea of how it all actually works (because they’re definitely not giving you that). So, with just that sort of elementary knowledge at hand, people don’t really know how to think of harmony in any other way, and they may just assume that what they were taught is more or less the Gospel truth.

I don’t want to be too critical here…. There are good pedagogical reasons for doing things this way, as I said, and it’s not like you should think of it as lying to children or whatever. But it can easily lead people astray, if they take their lessons too seriously or try to draw too many conclusions from them. Not so different from math, I guess. Plenty of things have to be re-learned or put somehow into a bigger picture, once you get to the more advanced stuff. (You know what I mean… sometimes “multiplication” isn’t commutative, three cube roots of 1, etc.) The trouble is that people will eventually receive something better than a 3rd grade math education, at least when their education system isn’t a total garbage fire, while that’s not how it typically works in music.

consciousness razor @14,

Well now you seem to be describing just intonation purists, of which I saw a few on the xenharmonic alliance page. LOL, I see that now the page is having backlash against the purists, which maybe means it was just a few recent bad apples. Hmm, maybe I should stop looking at internet communities that I have no involvement in, it feels so voyeuristic.

I can also recommend Syzygys, a Japanese duo who play pop music in Harry Partch’s 43-tone scale (one of the first tunes you may come across while searching for their music is “Fauna Grotesque” which is not particularly representative of their output – whether that’s a good or a bad thing depends on the listener). Also Philipp Gerschlauer has released some microtonal jazz with his group Besaxung.

I’ve done a bit of messing around with xenharmonic music, I found the Bohlen-Pierce scale an interesting one to work with – it’s a non-octave tuning that divides the “tritave” (3:1 frequency ratio) into 13 steps. Both equal temperament and just intonation versions exist (as I understand it, the scale was derived using just intonation and the equal temperament version – sometimes written 13-EDT – was created later). Sevish used it on the piece “Mashroon”, which is well worth checking out.

That was something new for me! Thank you Siggy and Kommentariat!

That’s super interesting. Now I am going to try to find microtonal operatic gothic music.

Is microtonal what Arvo Part is doing in pieces like Stabat Mater or is that just “weird chords”? What’s the term for that?

Thank you for opening up some new world to me.

Marcus Ranum @18,

I listened to some of Stabat Mater and did not detect any microtonality, although I could have easily missed it.

Microtonal operatic singing might be difficult to find (and goth? Who knows?). I think the place to look for that is among classical composers, which means Bandcamp might not be your place. The xenharmonic wiki has an impressive list of western classical composers, although not much information about each composer.

I just learned that Ligeti’s Clocks and Clouds is microtonal, although I think in an informal way.

That’s all 12-EDO. There are some elements that were much more common in the Renaissance and may seem unusual to you, mixed in with much more modern stuff that may also seem a bit unusual. But in a lot of ways, it’s fairly normal/not-weird. Just different.

Microtonal music (not 12-EDO) is pretty rare in general. Normal people (assuming you would count as one, in this respect) don’t hear much of it in their lives. There is a notable exception. It’s a lot more typical in film music, especially in the last few decades. So, if you want a taste, your chances are actually pretty decent if you go listen to a movie. (But many wouldn’t do this or wouldn’t notice, because of the explosions/magic/etc. on the screen.) Sometimes it’s on TV, but with shorter production times, less work goes into music for television, which constrains what composers are likely to do. It’s also sort of risky (read: the studio might lose money!), because it’s unfamiliar and people tend to dislike unfamiliar things, except in very specific circumstances. Sometimes you expect a certain sort of tension: far-out spacey mind-blowing shit, high drama, and whatnot … maybe in a horror flick, a fight scene, a death scene, or something of that nature.

Here’s a good one from Terry Riley: A Rainbow in Curved Air (40:26)

Riley plays multiple keyboards, slightly out of tune with each other, along with some percussion. Then soprano sax comes in … not sure if he played that too. Anyway, it goes to a bunch of strange places, especially in the second part (the B side).

Surprised that in a discussion of microtonality, Easley Blackwood’s 1980 “Twelve Microtonal Etudes for Electronic Music Media” hasn’t been mentioned.

YouTube link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HbuFPpiJL1o