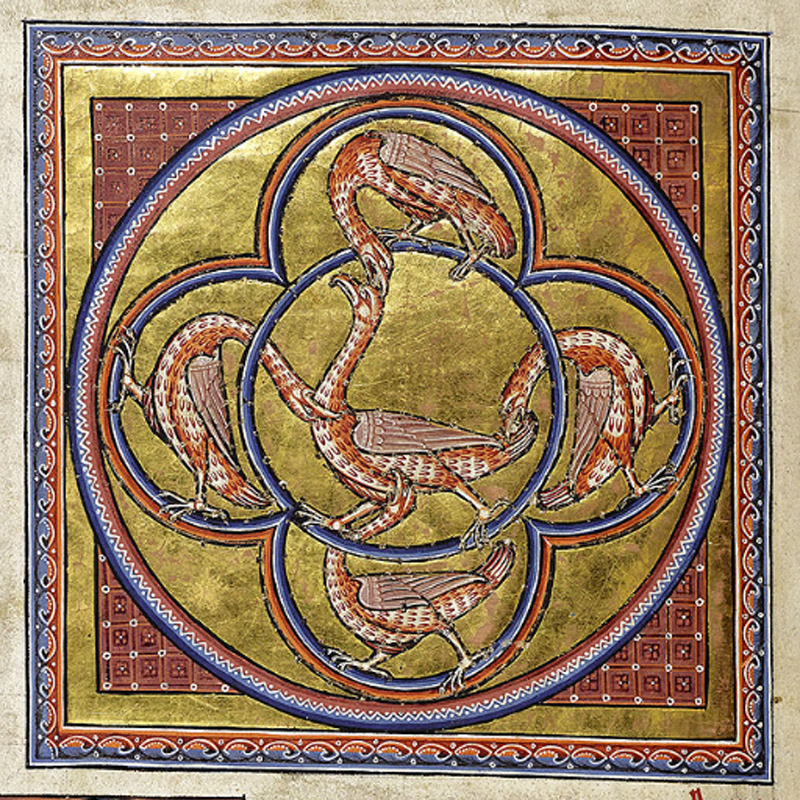

Portrait of the owl. This owl ‘bubo’ is tawny brown and beige with a flat face and prominent ears like horns. Bubo, as described by Aristotle (buas or bruas in Greek) was as large as an eagle which must indicate the relatively rare eagle owl. It has prominent ear tufts as shown but it is tawny all over and does not have a flat face. The long eared owl has a flat face and ears but is also tawny all over. The barn owl is closest in colouring to the illustration and also has a flat face, but it does not have ears. As projecting ears or horns are not mentioned in the Bestiary text they may derive from a much earlier source which was still aware of the connection between bubo and the eagle owl.

Text Translation:

Of the owl Isidore says of the owl: ‘The name owl, bubo, is formed from the sound it makes. It is a bird associated with the dead, weighed down, indeed, with its plumage, but forever hindered, too, by the weight of its slothfulness. It lives day and night around burial places and is always found in caves.’ On this subject Rabanus says: ‘The owl signifies those who have given themselves up to the darkness of sin and those who flee from the light of righteousness.’ As a result it is classed among the unclean creatures in Leviticus (see 11:16). Consequently, we can take the owl to mean any kind of sinner.

The owl gets its name from the sound it makes, because its mouth speaks when its heart is overfull, for what it thinks about in its mind, it utters with its voice. It is said to be a filthy bird, because it fouls its nest with its droppings, as the sinner dishonours those with whom he lives, by the example of his evil ways. It is weighed down with its plumage, as the sinner is with an excess of carnal pleasure and with fickleness of mind; but it is truly hampered by the weight of its sloth. It is hindered by the weight of its idleness and sloth, as sinners are lazy and slothful in acting virtuously. It spends its days and nights around burial places, as the sinner delights in sin, which is like the stench of decaying human flesh. For it lives in caves like the sinner who will not emerge from darkness by means of confession but detests the light of truth.

When other birds see the owl, they signal its presence with loud cries and harrass it with fierce assaults. In the same way, if a sinner comes into the light of understanding, he becomes an object of derision to the virtuous. And when he is caught openly in the act of sinning, his ears are filled with their reproaches. As the birds pull out the owl’s feathers and tear at it with their beaks, the virtuous censure the carnal acts of the sinner and condemn his excesses. The owl is known, therefore, as a miserable bird, just as the sinner, who behaves in the way we have described above, is a miserable man.

Folio 50r – the blackbird, continued. De bubone; Of the Owl.