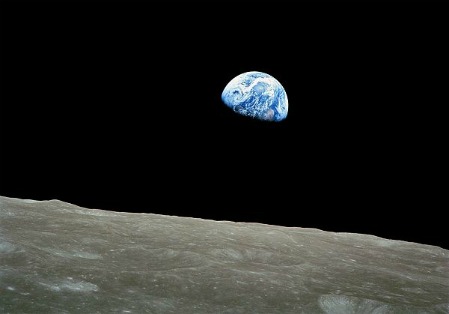

I remember it like it was yesterday: speeding through the empty north Texas prairie en route to a holiday rendezvous, Dec 25th, 1968 at 2 AM. I was lying above and behind the back seat, my seven-year old body easily stretched out on the old fashioned rear console, staring up through the slanted glass of a Ford sedan at a crystal clear nightscape. The winter stars were poured thick that night, spilling across the sky like powdered sugar. In a moment of pure synchronicity the radio replayed a newly arrived, static filled season’s greeting carried a quarter million miles on the gossamer wings of invisible light:

We are now approaching lunar sunrise and, for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you. … In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth …

My wonder aroused, the rest of the family dozing, I listened intently to mankind’s first message from another world, and asked my father about those brilliant stars burning cold in the night. He began to explain to me quietly, patiently, using analogies of distance a child could grasp. Something clawed up from the subconscious, an extraordinary stew of agoraphobia and wonder gripped me. And I fell into the sky.

In a jolt of acceleration it was as though I were flung out of the car and thrown head over heels off into the endless heavens, a mote of consciousness lost in immensity. It was terrifying, turning to exhilarating; then it was glorious. Who knows what cocktail of neurotransmitters was unleashed in my virgin brain that night. But one dose was all it took. I was mainlining cosmic eternity, and like a latent alcoholic feeling that first warm rush of bourbon, after my transcendental ride ended all I could think was I want some more.

The Apollo 8 reading of Genesis from the moon was the most watched and listened to broadcast in the world up to that time. People of every age and background were profoundly moved that night by the same transmission. It would later win an Emmy, the highest award given by the Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

Millions more the world over were affected in the same way in the years before and in the years after by the drama of human spaceflight. In the late 1950s, legions of excited onlookers flocked to dark pastures and barren desert to catch a fleeting glimpse of Sputnik and other early satellites racing among the stars. Russian school children still learn songs praising Yuri Gagarin, the first person in space. Millions of Americans proudly watched John Glenn lift off in a tiny capsule called Friendship 7 and listened in as he circled the world. Millions of ordinary people joined me in spirit in 1968 when Apollo 8 sent us a cosmic season’s greetings from the back side of the moon.

It is said that during Apollo 11, a billion people listened to radios or watched TV to share in the culmination of one of mankind’s greatest dreams. For a brief moment, the political turmoil and bitter debate dividing Americans from one another and the chilling prospect of cold war melted away, leaving us united not just as a nation, but as a world and a species. Even the failures generated intense interest: the world watched, holding its breath, as NASA battled to bring a severely wounded Apollo 13 and crew back to earth safely.

The effect on those of old enough to remember the triumphs of Apollo were profound. To this day many in my generation think of ourselves as space-race kids. The Children of Apollo. There are a lot of us. The interest in natural science spurred in children by the space-race is matched only by their fascination for dinosaurs. Our celestial inheritance included the belief that with hard work and brainpower, we could do anything. It wasn’t a cliché for us, repeated by teachers and parents hoping to see their children excel. It was innate, imprinted for life.

As impressive as all that is, many following the space program as youngsters in the 60s and 70s confidently assumed vacations on rotating space stations by the year 2000, a base on the moon, and great ships plying the interplanetary space lanes between earth and Mars. Wonder junkies and space race kids even have a cynical catch phrase for our disillusionment: dude, where’s my flying car? And yet so far, only a few hundred of earth’s billions have gone to space. Only 24 lucky people have ventured beyond low earth orbit and no one has crossed that boundary or visited the moon since 1972.

That’s all about to change in the decades ahead. There is a new wind blowing, part technological, part ideology. It is driven by Silicon Valley pioneers who have amassed great fortunes, fueled in part by the innovative spin offs of NASA come full circle, and the great wonder inspired by Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong’s one small step. These men and women are not content to wait on short-sight politicians fighting over the bones of NASA. They are not just obsessed with building the rockets and spacecraft that will guide us through our next small step. Readers of this blog will soon meet some of the visionaries determined to actually make that leap.

The effort to expand into the solar system until it becomes economically and culturally irreversible is known simply as Newspace.

I’ve enjoyed your columns on KOS for years, and have been an avid follower of the space program from the time Sputnik was launched in the 50’s. I must admit, though, that my impressions of that reading you refer to from Apollo 8 were quite a bit different than yours, and, I would suspect, most of the rest of the country. I had just returned from a tour in Vietnam, and was beginning a career in the computer industry primarily dealing in the aerospace marketplace. My impression of that reading was: Why is he reading a myth, a fairy tale, a story for children, when he should be reading some sort of tribute to the centuries of science that put him in the position he was in the first place. The earth-moon system his craft was navigating is 4.5 billion-years-old, not a few thousand, and it wasn’t the scribblings of bronze-age nomads that put him there, it was generations of work by people like Isaac Newton, Robert Goddard, Willey Ley, and thousands of others who shared the same vision.

I was struck by the incongruity of it all. A triumph of science, perhaps one of man’s greatest achievements, reduced to meaninglessness, and trivialized by NASA’s desire to pander to the vast majority of Americans’ who are afraid of the dark and terrified by the unknown. It was a real opportunity to educate, inform and inspire, but instead they chose to perpetuate fear, ignorance, and superstition.

Pete Soderman