Content Warning: Torture

After this, I am going to stop posting about torture, and resume being my usual fake happy soap-making, nihilist, anarchist, technology strategy-loving self. I promise.

Content Warning: Torture

After this, I am going to stop posting about torture, and resume being my usual fake happy soap-making, nihilist, anarchist, technology strategy-loving self. I promise.

I wanted to finish sunday’s piece on Epicurus’ asceticism with a lengthy quote from G. K. Chesterton’s Four Faultless Felons. [gutenberg] Chesterton can be relied upon to flip things beautifully on their head, and he does so.

When someone says “Epicurean” what comes to mind? Usually, it’s hedonism – life spent in the pursuit of pleasure. If we were raised in a christian tradition, we might even hear “Epicurean” as slightly louche or sexually promiscuous. Epicureans, many of us think, are the sort who wear velvet smoking jackets and snort cocaine off the upturned buttocks of prostitutes.

“That’s not fair!”

We seem to be on the fence about fairness: we want some things to be fair but not at our expense; suddenly it’s unfair to be taxed to support something we don’t agree with, when we would have happily paid the same taxes to support something we do like. I instantly spiral down into linguistic nihilism when I try to think through “what is ‘fair’?” in most cases, because all that I seem to be encountering is other people’s strongly-held opinions. But if we’re going to re-balance society, or decide who gets which slice of cake, we have to have a way of talking about what is fair.

A poster over at Charles Stross’ diary made a comment about nazis[1] that stuck in my mind for days, because he’s very right:

I started writing this as a sort of open snark-gram to Caitlyn Jenner, but I just couldn’t do it. As I started to think things through from different angles, I just got more and more depressed. So, I hit “Move to Trash” and tried again.

Root cause analysis, for me, always comes back to privilege, which is an instance of exceptionalism.

I grew up reading feats of military derring-do, and watching films like “Seven Samurai” and “Harakiri” – books and movies about martial glory and the character of the warrior. I noticed early on that a big piece of military glory and heroism is the stand against great odds – the acceptance that one’s mission will probably cost one’s life, but that’s a secondary concern: doing the right thing matters more. I read a lot about the samurai and bushido, and I always deeply felt the distinction between katsujin ken (the life-giving sword) and setsunin-to (the life-taking sword). Somehow it all ties together in my formative anarchy as part of something basically anti-authoritarian, because the authority and the establishment usually are the “powers that be” against which the life-giving sword must work.

Novelist Walter Mosley is a widely-published author of crime fiction, children’s books, and stories. He did a talk at “Politics and Prose”[Mosley] about his book “Folding the Red Into the Black: Developing a Viable Untopia for the 25th Century”[amazon]

I don’t like the term “common sense” because it’s an oxymoron – what is common is usually not sensible, and what is sensible is seldom common. Mosley dishes out something that is probably uncommon sense.

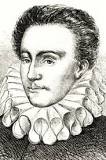

Étienne de La Boétie

This is not the first time, nor probably the last, that I will take you to visit the words of Étienne De Boétie. In 1549, De Boétie wrote one of the great essays in political philosophy[text] – a self-admittedly meandering piece that pondered the question why people follow dictators.

I wish you all a good year! Health and safety first and foremost, then all the other good things. I also wish you special strength and skill at one all-important task: telling fact from opinion.