Most Americans don’t know that reparations for slavery has already been attempted. It didn’t work. But that’s because the US did it wrong.

George to slavers: any questions?

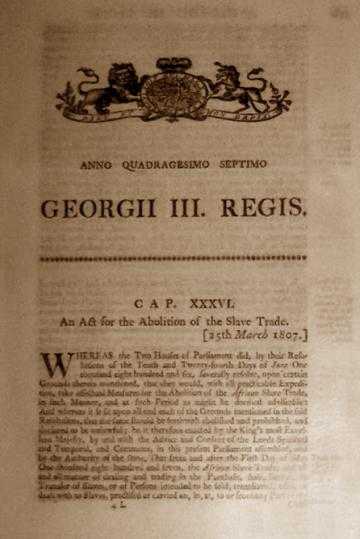

In the British empire, slavery was officially made illegal by the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act of 1807,[wik] making official the crown court’s decision in Somerset V. Stewart in 1772, [wik] which made slavery unenforceable in the empire. I’ve written elsewhere on the possible impact of Somerset V. Stewart on the North American colonies, which seceeded afterward, claiming that their liberties were being infringed. [stderr] Basically, the American colonists made the same argument that the US South states made: “you are taking away our freedom to hold other humans as un-free chattel, because we think freedom is super important when it’s our freedom we’re talking about.”

Notably, even after the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act was passed, there was still a great deal of slave trading going on in the Caribbean – including Caribbean plantation owners offloading their inventory of slaves to slave-owners in the US South. It took another law, the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 to impress on the British Empire’s various colonies that, “no, this time we really mean it, wot wot!” – although the act of 1833 exempted the “Territories in the possession of the East India Company” because the East India Company had really good lobbyists. To save you having to look up on a map, that’s most of what we’d call India today. The act of 1833 abolished slavery in Jamaica but slavery continued in Jamaica until 1838.

The legal thrashings-about of the British Empire, with regard to slavery, are an illustration of how much money there was tied up in the slave economy. You can’t just say “you are all free now!” Well, actually, you can, but what happens to the former slave-owners and the former slaves? Can you expect the former slave-owners to just roll up their sleeves and start cutting their own sugarcane? Not a chance. Can you expect the former slave-owners to sit down at a brotherly table of negotiation and offer the former slaves appropriate pay for the work that they used to do for “free”? That’s not going to happen, either. The grim reality of slavery is that it’s like snorting cocaine for your economy: it’s great for a while until you have to come down and take stock of reality. I don’t know about you, but my heart does not exactly bleed with pity for the former slave-owners but because of their reliance on slavery, they were also the economic powerhouses in whatever jurisdiction was looking at emancipation. In the US that translated into powerful plantation-owners in the South saying “when we free them they are going to run amok and kill and rape and drink and loot!” I.e.: do what they did. That was the great fear of slave-owners, and that fear was whipped up to a crawling existential dread when Georges Biassou and Toussaint L’Ouverture conclusively demonstrated that white people are not inherently superior by leading Haiti to a successful revolution in 1791 [wik] – notably the former slaves in Haiti agreed to continue working, after all, they needed an economy, but they refused to allow themselves to be whipped any more. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Haiti on the mental landscape of the slave-owner, and it also informs us somewhat of the impact of John Brown’s attempted slave rebellion on the Southern psyche.

So, what do you do? You offer reparations!

The Slavery Abolition Act of 1933 created a pool of £20,000,000 – according to [this] calculator that’s about £2.2 billion in today’s money, to compensate slave-owners for their losses: [wik]

Half of the money went to slave-owning families in the Caribbean and Africa, while the other half went to absentee owners living in Britain. The names listed in the returns for slave owner payments show that ownership was spread over many hundreds of British families, many of them (though not all) of high social standing. For example, Henry Phillpotts (then the Bishop of Exeter), with three others (as trustees and executors of the will of John Ward, 1st Earl of Dudley), was paid £12,700 for 665 slaves in the West Indies, whilst Henry Lascelles, 2nd Earl of Harewood received £26,309 for 2,554 slaves on 6 plantations.

That’s almost a Trumpian looting of the state’s wealth, but oligarchs gotta get paid, right? The slaves were getting their priceless freedom (to work) and the rich title-holders to the plantations got richer. This all happened well before Jim Crow in the US South, so lynching wasn’t a “thing” yet, but the less peace-loving of us might think that perhaps it was the wrong people decorating the trees. The surge of guillotining known as “The Terror” following the French Revolution accounted for a few thousand blue-blooded heads rolling; in my opinion the British and Americans probably needed a similar culling of their oligarchs. But that’s not how things ever work out; it’s always the slow and weak that take it on the chin; as you can see the wealthy British slave-owners were comfortable back in England, getting compensation from the crown for the slaves that were being freed at their investment properties in the Bahamas. The plantation bosses offered the newly freed workers chump change and grumbled that they couldn’t use the whip or rape anymore.

As oligarch Winston Churchill said, “The Americans always do the right thing, but only after all other options are exhausted” – speaking as one who knew. The US made similar attempts at reparations.

An Act for the Release of certain Persons held to Service or Labor within the District of Columbia

In the District of Columbia, Abraham Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act on April 16, 1862. [wik] That was three years, almost to the day, before he was shot to death (April 15, 1865) – compensated emancipation was not good enough for the slave-holders in the south.

The passage of the Compensated Emancipation Act came nearly nine months before the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. The act, which set aside $1 million, immediately emancipated slaves in Washington, D.C., giving Union slaveholders up to $300 per freed slave. An additional $100,000 allocated by the law was used to pay each newly freed slave $100 if he or she chose to leave the United States and colonize in places such as Haiti or Liberia.

and:

As a result of the act’s passage, 3,185 slaves were freed. However, the older fugitive slave laws were still applied to slaves who had run from Maryland to Washington, D.C. The slaves were still subject to the laws, which supposedly applied only to states, until their 1864 repeal.

See what Churchill meant about “exploring all the options”? Lincoln, the great emancipator, was basically offering to free a few slaves on condition that they’d fuck off out of the United States. And, even then, escapees like Frederick Douglass would not be safe in Washington where they were subject to capture under the fugitive slave laws.

We should not be discussing reparations, we should be discussing punitive damages.

Re: the second paragraph – it was the slave trade that became illegal in British territory in 1807, not slavery itself. The US made importing slaves from outside the US illegal around the same time, but that just encouraged the growth of a massive internal slave trade within the US.

There’s something really perverse about the notion of slave owners being paid restitution for no longer being able to own other human beings.

#2

@LykeX

Yes. But Lincoln’s view was that emancipation was cheaper than war. He offered compensated emancipation to the South, which refused.

Transatlantic slave trading became illegal in 1807 in the US. That did not mean it stopped.

Slaves were smuggled in from Cuba. The trade from Africa to Cuba stopped soon after the US Civil War. Wonder why….

So the people who had already reaped all the profits a slave’s labour got three times what the slave got, whose meagre compensation came with harsh conditionals attached? Truly Lincoln was the greatest president. It’s no wonder there’s a giant statue of him where thrifty capitalists can bow their heads in great respect.

The linked calculator says those 100$ would be equivalent to 3300$ today. While I have no idea what travel cost back then but given the lack of no frills airlines I’m not even sure that would get you to Liberia, or leave enough spare cash to start a new life. I suppose you could work for your passage, which would be a phenomenally bad start to an emancipated life. “The state set me free and paid me off to go away and I still can’t afford to go home!”

I suspect (or wildly surmise) that noone in Liberia was eagerly anticipating a wave of former slaves coming “home”, and that the US government chose this country by the very stately process of playing “pin the burden” with a map of Africa. Either that or using some weak argument amounting to something among the lines of, “well, that’s where we put all the people we had abducted on the boats.”

3300$ would be enough to exercise your second amendment right – form a militia of like-minded people in a similar situaton and an inclination againt tyranny – but I know better than to think the US constitution applies to everyone equally. Nope, I couldn’t stifle a chuckle at that ridiculous notion.