The theist exclaims, “Be careful not to worship the ferocious and strange God of theology; mine is much wiser and better; He is the Father of men; He is the mildest of Sovereigns; it is He who fills the universe with His benefactions!”

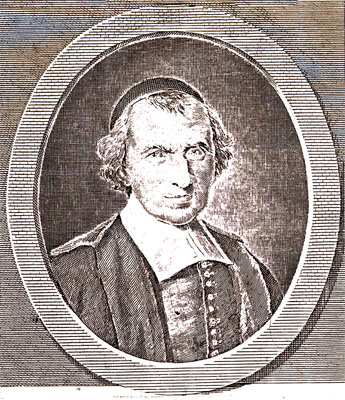

Your host, Jean Meslier

But I will tell him, do you not see that everything in this world contradicts the good qualities which you attribute to your God? In the numerous family of this mild Father I see but unfortunate ones. Under the empire of this just Sovereign I see crime victorious and virtue in distress. Among these benefactions, which you boast of, and which your enthusiasm alone sees, I see a multitude of evils of all kinds, upon which you obstinately close your eyes.

Compelled to acknowledge that your good God, in contradiction with Himself, distributes with the same hand good and evil, you will find yourself obliged, in order to justify Him, to send me, as the priests would, to the other life. Invent, then, another God than the one of theology, because your God is as contradictory as its God is. A good God who does evil or who permits it to be done, a God full of equity and in an empire where innocence is so often oppressed; a perfect God who produces but imperfect and wretched works; such a God and His conduct, are they not as great mysteries as that of the incarnation? You blush, you say, for your fellow beings who are persuaded that the God of the universe could change Himself into a man and die upon a cross in a corner of Asia. You consider the ineffable mystery of the Trinity very absurd Nothing appears more ridiculous to you than a God who changes Himself into bread and who is eaten every day in a thousand different places.

Well! are all these mysteries any more shocking to reason than a God who punishes and rewards men’s actions? Man, according to your views, is he free or not? In either case your God, if He has the shadow of justice, can neither punish him nor reward him. If man is free, it is God who made him free to act or not to act; it is God, then, who is the primitive cause of all his actions; in punishing man for his faults, He would punish him for having done that which He gave him the liberty to do. If man is not free to act otherwise than he does, would not God be the most unjust of beings to punish him for the faults which he could not help committing? Many persons are struck with the detail of absurdities with which all religions of the world are filled; but they have not the courage to seek for the source whence these absurdities necessarily sprung. They do not see that a God full of contradictions, of oddities, of incompatible qualities, either inflaming or nursing the imagination of men, could create but a long line of idle fancies.

Today’s deist might reply to Meslier that he is strawmanning their god; a god might create the universe in all its vastness then go take a long long break at Starbuck’s and more or less forget about it. There is no need for such a god to be concerned with justice and right and wrong – it’s the “god that walked away.” I’ve never had much respect for that opinion, either, since such a god is a useless god and serves simply as a placeholder for the coward who cannot cope with the idea that the universe has no meaning other than what we assign, and it very much appears to have sprung into existence rather suddenly billions of years ago – and the laws of physics are what shape and constrain it. “Where did those physical laws come from, then?” We may never know, and who gives a shit, anyway?

I have discussed this with deists, who declare that it’s a reasonable position for a skeptic to take. But I think it’s not – a more reasonable position for a skeptic to take is that there is no god at all, because there is no sign of one and never has been. The universe does not require a god to poof it into existence – it appears to have done that fairly well on its own. The skeptical deist should be able to offer evidence that their god exists, which is better than the evidence that black holes exist. Poor benighted deists wind up worshipping the universe itself.

Finally, deism becomes a god of the gaps argument – there must be something because nothing comes from nothing. That’s just human small-mindedness; how can we look upon something as Sagittarius A* and say “something as awesome as that cannot have simply created itself by absorbing stars and light and dust!” Yet, that’s exactly what it did. If there is a deist’s god, it did not create the universe for us, anyhow, it created the universe for the black holes. The god that walked away sure loves some black holes.

There is a thing at the center of that mass of suns, that weighs so much that the entire mass orbits around it. Perhaps the deists’ god wandered into a supermassive black hole and that’s why nobody has heard from it since the big bang.

Its mass is only between 10^-5 and 10^-6 times the mass of the galaxy. If it magically disappeared, most of the galaxy would carry on with minor orbital adjustments.

Rob Grigjanis@#1:

Its mass is only between 10^-5 and 10^-6 times the mass of the galaxy

That’s heavy, right?

So is the galaxy sort of a vortex-like swirl that creates the black hole because it’s at the center of the vortex? I thought that the supermassive acted more like a drain that the galaxy is swirling down. From your comment it appears I have my gravitic cause/effect backwards?

I remember reading somewhere that Sagittarius A* is about the size of our solar system out to the orbit of Saturn. And, because of the angular momentum of stuff falling into it, it’s probably spinning at close to light speed. Supermassive black holes are so awe-inspiring I think they may be worth worshipping a bit.

Marcus:

…

You seem to neglect the gravity of the dark matter, suns, dust, etc. outside of the black hole. Black holes arise by collapsing matter at the center because of the gravity of the whole galactic system. Then they just become part of it.

I’d say he was addressing theists, not deists. For all I know, he may have thought deists weren’t even worth his time.

If that marks the first moment of time — it may not, we don’t yet know — then there was nothing “sudden” about it. Or protracted. Because you could only say something like that of a process which occurs over a (long or short) period of time.

I think that’s a silly question. First, it’s not literally meant to a be “where” question, of course, but more like “how” question. But on a more serious note, there’s a lot of philosophy on this already. Many people see a lot of problem with the that physical laws constrain the world (or “govern” or “tell it how it should behave” like political laws), since it’s not clear what the hell kind of thing could possibly do that, if one is claiming it exists. And you can add “how they came to be” onto this, but your troubles really only start there.

So, some take a position which is inspired by Hume. (And they’ve really run with it over the centuries … to me, Hume seems the kind of guy who’d be okay with it.) The Humean view is that physical laws are not extra things you need to account for, on top of all of the other existing stuff (i.e., the universe). They’re just particularly interesting facts about it, but not metaphysically different from any other boring, old, mundane facts like what you had for lunch last Thursday. They’re interesting to us, because they summarize a whole lot of things about the world in a very efficient form. It’s worth emphasizing that, as summaries which are doing a certain kind of job for us in science, they’re made by people and put in a language and a form we can understand and use (mostly math).

So, there is no further question about where the laws came from or how they do what they do. You can ask such questions about the universe or things exising in it; but to the extent you consider such things settled, then you don’t need to fuss about laws. Because they just sort of come along for the ride, and we make them up in the process of trying to answer questions about the world.

They’re not playing the role of a God which is reigning over it all and dictating how all of it should be. Of course, that’s what the word “laws” might suggest, but that’s just for historical reasons – way back when, many important scientists/philosophers did think God governed the world, so from that starting point, it’s straightforward to think it works according to laws he put in place. But for us, “laws” is nothing more than a sort of funny word to be using for “extremely useful, simple, factual summaries.”

Well, Rob might want to chime in, but “cause and effect” aren’t really what you need here. If we just assume Newtonian gravity for simplicity, two masses attract one another — inverse square law, you know the drill. Anyway, it’s not like one mass is the cause and the other is the effect. They both just move around in a certain way. The Earth is “pulling” down on you; but you are also pulling up on it.

So you should picture the whole mass distribution in the galaxy, ask where it is and which way individual things will fall in that big mess. (Hopefully, if you’ve got the right picture, it will do just as you should expect. Doing some actual calculations should back that up, with corrections for GR obviously.) Like Rob said, the black hole isn’t doing all that much by itself, but that’s compared to everything else in the entire galaxy. So I guess if we’re comparing it to other random things in the galaxy (every one of them smaller), then sure, it’s doing more than its fair share. It’s a rich guy, but one who lives in a very large economy.

Marcus @2:

Heavy is relative. It’s millions of times heavier than the sun, yeah. But it’s misleading to say the rest of the galaxy orbits the BH in the sense that the planets orbit the sun. It’s the biggest bit player in a cast of hundreds of billions.

I don’t know enough about galaxy formation to say which came first; the galaxy or the BH. But I don’t think it’s like stuff swirling down a drain. Far enough away from it, it’s just another massive object, with stuff orbiting it.

Consciousness Razor@#4:

The Humean view is that physical laws are not extra things you need to account for, on top of all of the other existing stuff (i.e., the universe). They’re just particularly interesting facts about it, but not metaphysically different from any other boring, old, mundane facts like what you had for lunch last Thursday. They’re interesting to us, because they summarize a whole lot of things about the world in a very efficient form. It’s worth emphasizing that, as summaries which are doing a certain kind of job for us in science, they’re made by people and put in a language and a form we can understand and use (mostly math).

I agree with that. I’d probably say that they are “emergent properties” – all this stuff (including black holes at the center of galaxies) are emergent organization that results from the way things are. I agree with you that it’s Humean, but it’s also almost Epicurean [Epicurus spoiled and otherwise great exercise in saying “meh” by making up a lot of his own physics, which was a bunch of more or less good guesses]

You can ask such questions about the universe or things existing in it; but to the extent you consider such things settled, then you don’t need to fuss about laws. Because they just sort of come along for the ride, and we make them up in the process of trying to answer questions about the world.

I like your description of that, and I agree. Theists (and arguably deists who want a god that did more work than pushing a button and walking away) sometimes try to leverage the facts about the universe, i.e.: “gosh it’s so big!” to imply a god was necessary. I may not have adequately conveyed my attitude, which is “gosh it’s so big! that’s awesome! who needs to understand where it came from?!” I mean, it would be nice. But the fact that there are supermassive black holes does not imply a god and it certainly does not imply a god that fetishises self-murder using Romans as the instrument of its transcendence.

But for us, “laws” is nothing more than a sort of funny word to be using for “extremely useful, simple, factual summaries.”

Right, and I agree. Physical laws are descriptions of the way things actually work; they’re a way of organizing our understanding. It’s much easier to say that all objects appear to behave in a certain way than to be specific unless it’s necessary to be specific because they don’t appear to behave that way. My impression of “physical law” is that it’s the most parsimonious explanation for our understanding of observed reality.

Theists seem to think that “law” conveys some special imprimatur, which I think I’d blame on the legislative slant of judeo-christian religion. You know: physical law is like the ten commandments, only it’s right more often. Something like that.

Like Rob said, the black hole isn’t doing all that much by itself, but that’s compared to everything else in the entire galaxy. So I guess if we’re comparing it to other random things in the galaxy (every one of them smaller), then sure, it’s doing more than its fair share.

Yup. I don’t think that there’s anything special about a supermassive black hole other than “damn, that’s supermassive.”

Rob Grigjanis@#5:

But it’s misleading to say the rest of the galaxy orbits the BH in the sense that the planets orbit the sun.

I did not understand that, before, and now I do. Thank you. [Well, I understand that I did not understand. That doesn’t mean I understand galaxy formation!]

I think my brain was tripped up by the similarity to water going down a drain, and the whole “gravity well” thing. It looks to me like the galaxy is swirling down the black hole. Of course all the water swirling down the drain is what makes the drain a drain; there’s no drainfulness without the water.

I think the concept that is most useful in physical mechanics is that of the center of mass, or barycenter. Once you start thinking of things like the solar system as a collective of bodies with a center of mass that is not static, but something that changes over time, and can be inside the sun or a short distance from the sun (collective effect of the outer giants), it becomes a lot easier to explain heliocentrism: “While it is true that you can model the motions of the bodies of the solar system as from the center of the Earth (relativist Tychonian geocentrism), you can also model those motions from the centers of the Moon, or Mercury, or Mars, or even a putative teapot between Earth and Mars. But the center of mass of the solar system is nevertheless inside the sun, or very near the sun.”

And the same goes for understanding the motion of the suns in galaxy. They are not orbiting the black hole just because it’s the most massive thing around, but because it’s at the center of mass of all their masses, which is why “If [the central black hole] magically disappeared, most of the galaxy would carry on with minor orbital adjustments.”

OK — I waited.

Um, he certainly ain’t talking about what I would call Deism.

The anthropomorphism of the concept of a ‘break’, for instance, cannot apply to a Deist deity, any more than the concept of a ‘personality’.

—

Were that way inclined, I’d fancy more a committee with a higher-than-usual membership of the clueless as an explanation for our reality, moreso than some singular entity. A cheap kludge, but good enough for government work.

This is one of the reasons that I’m quite fond of the Norse pantheon – yes, there are gods, but they’re drunk all the time and they fight amongst themselves a lot.

Astrophysicist Ethan Siegel compares black holes to the Cookie Monster:

“No, Black Holes Don’t Suck Everything Into Them“