Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, and full of wonder, emerged from their villages onto the island’s beaches and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly, the Arawaks ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts. He later wrote of this in his log:

They … brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells. They willingly traded everything they owned… . They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features…. They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane… . They would make fine servants…. With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.

These Arawaks of the Bahama Islands were much like Indians on the mainland, who were remarkable (European observers were to say again and again) for their hospitality, their belief in sharing. These traits did not stand out in the Europe of the Renaissance, dominated as it was by the religion of popes, the government of kings, the frenzy for money that marked Western civilization and its first messenger to the Americas, Christopher Columbus.

Columbus wrote:

As soon as I arrived in the Indies, on the first Island which I found, I took some of the natives by force in order that they might learn and might give me information of whatever there is in these parts.The information that Columbus wanted most was: Where is the gold? He had persuaded the king and queen of Spain to finance an expedition to the lands, the wealth, he expected would be on the other side of the Atlantic-the Indies and Asia, gold and spices. For, like other informed people of his time, he knew the world was round and he could sail west in order to get to the Far East.

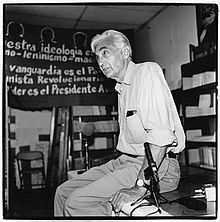

– Howard Zinn “The People’s History”

Recently there has been a resurgence of criticism of Zinn’s history, now that he is safely dead and buried and can no longer defend himself. That’s a fairly common pattern when someone who had a lot to say and was unafraid to defend their views, dies. I don’t think it’s unreasonable to consider the strategic timing of such critiques, nor is it unreasonable to ask the critic, “what do you think Howard would have said in response when he was alive?” In fact, Zinn already addressed those questions fairly well:

America’s future is linked to how we understand our past. For this reason, writing about history, for me, is never a neutral act. By writing, I hope to awaken a great consciousness of racial injustice, sexual bias, class inequality, and national hubris. I also want to bring into the light the unreported resistance of people against the power of the Establishment: the refusal of the indigenous to simply disappear; the rebellion of Black people in the antislavery movement and in the more recent movement against racial segregation; the strikes carried out by working people all through American history in attempts to improve their lives.

To omit these acts of resistance is to support the official view that power only rests with those who have the guns and possess the wealth. I write in order to illustrate the creative power of people struggling for a better world. People, when organized, have enormous power, more than any government. Our history runs deep with the stories of people who stand up, speak out, dig in, organize, connect, form networks of resistance, and alter the course of history.

In the introduction to some versions of The People’s History, Zinn explains his belief that all history is a result of the historian selecting the incidents and trends that they consider interesting and important, and weaving them together to explain something about the past. As he says, that means history is a matter as much of what is left out, as of what is put in.

In the introduction to some versions of The People’s History, Zinn explains his belief that all history is a result of the historian selecting the incidents and trends that they consider interesting and important, and weaving them together to explain something about the past. As he says, that means history is a matter as much of what is left out, as of what is put in.

I must explain my point of view. It’s obvious in the very first pages of the larger edition of The People’s History, when I tell about Columbus, and emphasize not his navigational skill and fortitude in making his way to the western hemisphere, but his cruel treatment of the indians he found here; torturing them, exterminating them in his greed for gold, his desperation to bring riches back to his patrons back in Spain. In other words, my focus is not of the achievements of the heroes of traditional history, but on all those people who were the victims of those achievements, who suffered silently or fought back magnificently. To emphasize the heroism of Columbus and his successors, as navigators and discoverers, and to de-emphasize their genocide is not a technical necessity, but an ideological choice. It serves, unwittingly, to justify what was done.

My point is not that we must, in telling history, accuse, judge, condemn Columbus in absentia. It’s too late for that. It would be a useless scholarly exercise in morality. But the easy acceptance of atrocities, as a deplorable but necessary price to pay for progress – Hiroshima and Vietnam to save “western civilization” – Kronstadt and Hungary to save socialism – nuclear proliferation to save us all – that is still with us. One reason that these atrocities are still with us is that we have learned to bury them in a mass of other facts, as radioactive wastes are buried in containers in the Earth. We have learned to give them exactly the same proportion of attention that teachers and writers often give them in the most respectable of classrooms and textbooks. This learned sense of moral proportion, coming from the apparent objectivity of the scholar, is accepted more easily than when it comes from politicians at press conferences. It is, therefore, more deadly.

Those that are accusing Zinn of stacking the deck of history are arguing that he should stack it, perforce, differently. But how? When one complains that Zinn is focusing not enough on the good things that Columbus brought, they are basically recapitulating a Monty Python sketch; “Yes but look at all the good things that the Romans have done for us!” Zinn says that he has set out to offer a different perspective on history; his critics who accuse him of using non-mainstream sources are saying that he succeeded in his stated objective, which was to use non-mainstream sources.

The Blackstone audiobook of Zinn is narrated by Matt Damon. I wish they had Samuel Jackson do it.

But that’s precisely what that historical instance shows.

Via the “official view”, given what you have written.

—

Also, the “noble savage” is a myth. People are people.