This is a piece I stumbled across a few years ago; it’s interesting, especially considering when it was written: 1949. The author was looking back at Europe’s successive troubles and accurately saw the disturbance as an effect of the economics of the industrial revolution. The analysis seems pretty simple to me: imperialism was waning and the vast changes in the European powers’ economies brought on by new industrial processes (in particular, weaponry) created a perfect storm of events that – for a time – discredited capitalism. The Russian revolution was through the process of turning into Stalin’s dictatorship – discrediting communism in turn. Aristocracy, in the form of the family of elite pinheads who destroyed Europe, didn’t look particularly good, either.

Innumerable voices have been asserting for some time now that human society is passing through a crisis, that its stability has been gravely shattered. It is characteristic of such a situation that individuals feel indifferent or even hostile toward the group, small or large, to which they belong. In order to illustrate my meaning, let me record here a personal experience. I recently discussed with an intelligent and well-disposed man the threat of another war, which in my opinion would seriously endanger the existence of mankind, and I remarked that only a supra-national organization would offer protection from that danger. Thereupon my visitor, very calmly and coolly, said to me: “Why are you so deeply opposed to the disappearance of the human race?”

I am sure that as little as a century ago no one would have so lightly made a statement of this kind. It is the statement of a man who has striven in vain to attain an equilibrium within himself and has more or less lost hope of succeeding. It is the expression of a painful solitude and isolation from which so many people are suffering in these days. What is the cause? Is there a way out?

It is easy to raise such questions, but difficult to answer them with any degree of assurance. I must try, however, as best I can, although I am very conscious of the fact that our feelings and strivings are often contradictory and obscure and that they cannot be expressed in easy and simple formulas.

Man is, at one and the same time, a solitary being and a social being. As a solitary being, he attempts to protect his own existence and that of those who are closest to him, to satisfy his personal desires, and to develop his innate abilities. As a social being, he seeks to gain the recognition and affection of his fellow human beings, to share in their pleasures, to comfort them in their sorrows, and to improve their conditions of life. Only the existence of these varied, frequently conflicting, strivings accounts for the special character of a man, and their specific combination determines the extent to which an individual can achieve an inner equilibrium and can contribute to the well-being of society. It is quite possible that the relative strength of these two drives is, in the main, fixed by inheritance. But the personality that finally emerges is largely formed by the environment in which a man happens to find himself during his development, by the structure of the society in which he grows up, by the tradition of that society, and by its appraisal of particular types of behavior. The abstract concept “society” means to the individual human being the sum total of his direct and indirect relations to his contemporaries and to all the people of earlier generations. The individual is able to think, feel, strive, and work by himself; but he depends so much upon society – in his physical, intellectual, and emotional existence – that it is impossible to think of him, or to understand him, outside the framework of society. It is “society” which provides man with food, clothing, a home, the tools of work, language, the forms of thought, and most of the content of thought; his life is made possible through the labor and the accomplishments of the many millions past and present who are all hidden behind the small word “society.”

It is evident, therefore, that the dependence of the individual upon society is a fact of nature which cannot be abolished – just as in the case of ants and bees. However, while the whole life process of ants and bees is fixed down to the smallest detail by rigid, hereditary instincts, the social pattern and interrelationships of human beings are very variable and susceptible to change. Memory, the capacity to make new combinations, the gift of oral communication have made possible developments among human being which are not dictated by biological necessities. Such developments manifest themselves in traditions, institutions, and organizations; in literature; in scientific and engineering accomplishments; in works of art. This explains how it happens that, in a certain sense, man can influence his life through his own conduct, and that in this process conscious thinking and wanting can play a part.

Man acquires at birth, through heredity, a biological constitution which we must consider fixed and unalterable, including the natural urges which are characteristic of the human species. In addition, during his lifetime, he acquires a cultural constitution which he adopts from society through communication and through many other types of influences. It is this cultural constitution which, with the passage of time, is subject to change and which determines to a very large extent the relationship between the individual and society. Modern anthropology has taught us, through comparative investigation of so-called primitive cultures, that the social behavior of human beings may differ greatly, depending upon prevailing cultural patterns and the types of organization which predominate in society. It is on this that those who are striving to improve the lot of man may ground their hopes: human beings are not condemned, because of their biological constitution, to annihilate each other or to be at the mercy of a cruel, self-inflicted fate.

If we ask ourselves how the structure of society and the cultural attitude of man should be changed in order to make human life as satisfying as possible, we should constantly be conscious of the fact that there are certain conditions which we are unable to modify. As mentioned before, the biological nature of man is, for all practical purposes, not subject to change. Furthermore, technological and demographic developments of the last few centuries have created conditions which are here to stay. In relatively densely settled populations with the goods which are indispensable to their continued existence, an extreme division of labor and a highly-centralized productive apparatus are absolutely necessary. The time – which, looking back, seems so idyllic – is gone forever when individuals or relatively small groups could be completely self-sufficient. It is only a slight exaggeration to say that mankind constitutes even now a planetary community of production and consumption.

That’s an excellent summary of the situation; human nature and nurture, natural inequality (per Rousseau) and social inequality. Obviously this is an argument that carries weight with me (let me repeat it):

It is “society” which provides man with food, clothing, a home, the tools of work, language, the forms of thought, and most of the content of thought; his life is made possible through the labor and the accomplishments of the many millions past and present who are all hidden behind the small word “society.”

To me, the set-up is to acknowledge that selfishness, or a zero-sum attitude toward cooperative participation in society, is an implicitly anti-social form of selfishness.

I have now reached the point where I may indicate briefly what to me constitutes the essence of the crisis of our time. It concerns the relationship of the individual to society. The individual has become more conscious than ever of his dependence upon society. But he does not experience this dependence as a positive asset, as an organic tie, as a protective force, but rather as a threat to his natural rights, or even to his economic existence. Moreover, his position in society is such that the egotistical drives of his make-up are constantly being accentuated, while his social drives, which are by nature weaker, progressively deteriorate. All human beings, whatever their position in society, are suffering from this process of deterioration. Unknowingly prisoners of their own egotism, they feel insecure, lonely, and deprived of the naive, simple, and unsophisticated enjoyment of life. Man can find meaning in life, short and perilous as it is, only through devoting himself to society.

The economic anarchy of capitalist society as it exists today is, in my opinion, the real source of the evil. We see before us a huge community of producers the members of which are unceasingly striving to deprive each other of the fruits of their collective labor – not by force, but on the whole in faithful compliance with legally established rules. In this respect, it is important to realize that the means of production – that is to say, the entire productive capacity that is needed for producing consumer goods as well as additional capital goods – may legally be, and for the most part are, the private property of individuals.

That second paragraph is powerful stuff:

We see before us a huge community of producers the members of which are unceasingly striving to deprive each other of the fruits of their collective labor – not by force, but on the whole in faithful compliance with legally established rules.

The author is perceptive; anarcho-capitalism has resulted in societies in which the rich have written the laws to read:

1) The rich get richer

2) Screw you

For the sake of simplicity, in the discussion that follows I shall call “workers” all those who do not share in the ownership of the means of production – although this does not quite correspond to the customary use of the term. The owner of the means of production is in a position to purchase the labor power of the worker. By using the means of production, the worker produces new goods which become the property of the capitalist. The essential point about this process is the relation between what the worker produces and what he is paid, both measured in terms of real value. Insofar as the labor contract is “free,” what the worker receives is determined not by the real value of the goods he produces, but by his minimum needs and by the capitalists’ requirements for labor power in relation to the number of workers competing for jobs. It is important to understand that even in theory the payment of the worker is not determined by the value of his product.

Private capital tends to become concentrated in few hands, partly because of competition among the capitalists, and partly because technological development and the increasing division of labor encourage the formation of larger units of production at the expense of smaller ones. The result of these developments is an oligarchy of private capital the enormous power of which cannot be effectively checked even by a democratically organized political society. This is true since the members of legislative bodies are selected by political parties, largely financed or otherwise influenced by private capitalists who, for all practical purposes, separate the electorate from the legislature. The consequence is that the representatives of the people do not in fact sufficiently protect the interests of the underprivileged sections of the population. Moreover, under existing conditions, private capitalists inevitably control, directly or indirectly, the main sources of information (press, radio, education). It is thus extremely difficult, and indeed in most cases quite impossible, for the individual citizen to come to objective conclusions and to make intelligent use of his political rights.

The situation prevailing in an economy based on the private ownership of capital is thus characterized by two main principles: first, means of production (capital) are privately owned and the owners dispose of them as they see fit; second, the labor contract is free. Of course, there is no such thing as a pure capitalist society in this sense. In particular, it should be noted that the workers, through long and bitter political struggles, have succeeded in securing a somewhat improved form of the “free labor contract” for certain categories of workers. But taken as a whole, the present day economy does not differ much from “pure” capitalism.

Production is carried on for profit, not for use. There is no provision that all those able and willing to work will always be in a position to find employment; an “army of unemployed” almost always exists. The worker is constantly in fear of losing his job. Since unemployed and poorly paid workers do not provide a profitable market, the production of consumers’ goods is restricted, and great hardship is the consequence. Technological progress frequently results in more unemployment rather than in an easing of the burden of work for all. The profit motive, in conjunction with competition among capitalists, is responsible for an instability in the accumulation and utilization of capital which leads to increasingly severe depressions. Unlimited competition leads to a huge waste of labor, and to that crippling of the social consciousness of individuals which I mentioned before.

This crippling of individuals I consider the worst evil of capitalism. Our whole educational system suffers from this evil. An exaggerated competitive attitude is inculcated into the student, who is trained to worship acquisitive success as a preparation for his future career.

The whole piece is worth reading, and I won’t quote it all because it’s probably worthwhile for you to know where it can be found – you may want to send links to your favorite anarcho-capitalists or aristocrats, should you know any. It’s at Monthly Review [mr]

The whole piece is worth reading, and I won’t quote it all because it’s probably worthwhile for you to know where it can be found – you may want to send links to your favorite anarcho-capitalists or aristocrats, should you know any. It’s at Monthly Review [mr]

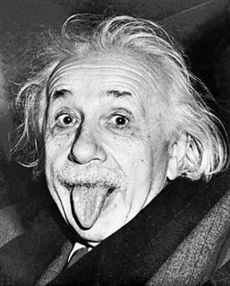

The author is Albert Einstein.

I have occasionally heard arguments to the effect that central planning for economies is not efficient. What’s interesting is that such arguments presuppose that capitalism is efficient. The problem with that reasoning is that capitalism is efficient for the capitalists – a free market is an efficient way of maximizing the market-maker’s profits. But, oddly, capitalists frequently create “winner take all” situations in which the customer-base is going to be divided in hopes that competitors can co-compete by building a duplicated, incompatible, set of offerings. Think VHS versus Betamax, AT&T versus Verizon, some shitty airline with cramped seats versus another shitty airline with identically cramped seats. This is a monopoly by two instead of a monopoly by one, and the end result is no better than if there was a centrally planned economy planned by imbeciles who said “let’s build two phone companies, with parallel infrastructure, and allow them to be exactly as bad as they can be and still survive” where is the efficiency in that? In the US, today, we do, in fact, have what amounts to a centrally planned economy – the entire economy has been distorted, as Einstein says, to serve the interests of the capitalists. They planned it that way.

In case any of you are concerned that I am making an argument from authority, I am not: I am not saying “this is right because it’s Albert Einstein.” I am saying “this is right and – oh, hey, look! It’s by Albert Einstein!”

Words that actually exist: duopoly

Two thoughts on arguments from efficiency:

Firstly, what do we mean by “efficiency”? Efficiency is a ratio of some output to some input. Surely it must be obvious that there are many different efficiencies, and that an arrangement which is efficient in one sense is going to be inefficient in others? We’ve largely been conditioned to think of efficiency in very narrow terms, defined by the owners of capital.

Secondly, is efficiency (however you define it) really the most important consideration anyway?

I’ve noticed this as well. I think there’s a reasonable argument for saying that profit business constitutes theft. The worker is never paid the actual value of the work done. If they were, there’d be no profits to skim off the top.

LykeX@#3:

I think there’s a reasonable argument for saying that profit business constitutes theft. The worker is never paid the actual value of the work done. If they were, there’d be no profits to skim off the top.

You’ve identified one of the big problems with Marxian theory that a lot of people have spilled ink over. Basically, Marx is trying to establish a theory of the value of labor so that we can talk about what is a “reasonable” profit. So, if you take 16 tons of ore and use labor to turn that into steel – Marxians want to be able to connect the value of the labor to the value that was created when the ore was turned into steel: the higher price of the steel ought to reflect the cost of the labor that refined it. And, when that steel is turned into a bridge, also with labor, the value of the bridge ought to be greater because the labor that turned those I-beams into a bridge was an incremental addition of value. The whole argument about the value of labor was because Marx (correctly, IMO) identified that the owners of the means of production were using that as leverage to control labor.

I haven’t done a write-up about it, yet, but a crucial book in forming my attitudes on this issue was Meet You In Hell [amazn] which is about Carnegie and Frick and the rise of American industrial capitalism. Reading about them made me understand what Marx was reacting to, and what Landes was describing in The Unbound Prometheus – massive social upheaval as agricultural economies changed into industrial economies and those who controlled the means of production made unbelievably fast fortunes at the expense of the laborers they exploited. Today, we can look at Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk…

So, the question “profit constitutes theft” hinges on your theory of labor value. Because otherwise the capitalist says (as they do!) “look at the jobs I created!” and “hey, they chose to work in my steel mill!” while labor has to point out that the jobs created were shit jobs and the capitalist carefully constructed the situation so there was no alternative. It’s tricky. And, natually, the apologists for capitalism are well-funded and well-educated and aligned with the media that carries their message.

If they were, there’d be no profits to skim off the top.

Right. The capitalist says (as they do!) “that is my fair share, because I created these jobs and I provided the means of production, uh, thank me.”

Reginald Selkirk@#1:

Words that actually exist: duopoly

Yeah. I liked the way it sounded, better, the way I wrote it. And I was also thinking of mentioning that there are more than 2 phone companies, more than 2 air lines with cramped shitty seats, etc. We don’t quite have duopolies – we have a clusteropoly where all the alternatives (thanks to market pressure) are more or less the same and all suck about equally.

Dunc@#2:

Firstly, what do we mean by “efficiency”? Efficiency is a ratio of some output to some input. Surely it must be obvious that there are many different efficiencies, and that an arrangement which is efficient in one sense is going to be inefficient in others? We’ve largely been conditioned to think of efficiency in very narrow terms, defined by the owners of capital.

Yes, it’s coincidentally convenient that “efficiency” means what is efficient for the rich. It’s as though they get to control our language, as well as our economy.

Secondly, is efficiency (however you define it) really the most important consideration anyway?

I don’t think that the capitalists make a very good argument for that. They assert it and move on.

What about an inefficient society in which everyone was happy? Well, there might not be enough surplus production for capitalists, politicians, and elites to divert for their own purposes, and then there’d be considerable unhappiness in that sector of the economy. Labor, naturally, would say, “you can grab that shovel over there and get busy!” but, you know, these hands weren’t made to work with a shovel.

Props to Dr. E. for this sarcastic usage of “so-called”, viz:

There’s even a word for that: it’s caled oligopoly.

wereatheist@#8:

There’s even a word for that: it’s caled oligopoly.

My new word for the day!

I wanted to get “cluster” in there to imply “clusterfuck” – I don’t think that the competition arrangement in, say, mobile communications industry, has resulted in anything remotely resembling efficiency. When I think about it, it’s mind-boggling: we’ve built, what, 3 completely separate parallel wireless networks? What’s the infrastructure cost for that? (It may be 5 for all I know but with the peering partnerships it’s hard to tell)

Yeah, but it should have been ‘polypoly’. :)

—

OTOH, it’s a redundancy — why have all the eggs in one basket?

John Morales@#10:

OTOH, it’s a redundancy — why have all the eggs in one basket?

Actually, because they are non-integrated competitors, each of them is internally redundant. So they didn’t just build data networks that’d get the job done, they build multi- redundant data networks. If we have 5 carriers, we have 10 networks.

It is “society” which provides man with food, clothing, a home, the tools of work, language, the forms of thought, and most of the content of thought; his life is made possible through the labor and the accomplishments of the many millions past and present who are all hidden behind the small word “society.”

To me, the set-up is to acknowledge that selfishness, or a zero-sum attitude toward cooperative participation in society, is an implicitly anti-social form of selfishness.

At school my mother was taught to be selfless, to always devote herself to others, to work hard for the benefit of the state so that people could finally build the promised communist utopia. At first she bought the ideology. Then she noticed that everybody around her was pretty selfish and she was the only selfless fool who got abused and exploited by everybody else. This resulted in my mom teaching me to always be selfish and to never care about others.

Personally I see this as a form of prisoners’ dilemma. If I’m part of a society (or a smaller subgroup) where everybody cares about others and behaves selflessly, then I’m willing to do so as well. However, if I end up in a group of selfish people, I refuse to be the only fool who gets exploited by others. I have witnessed and been part of different groups with various norms and generally I just adjust my behavior to match that of others.

Man can find meaning in life, short and perilous as it is, only through devoting himself to society.

No, I’d say this is not correct. There are multiple ways how a person can find meaning in their life (in my case that would be hedonism and entertainment for myself).

I have occasionally heard arguments to the effect that central planning for economies is not efficient. What’s interesting is that such arguments presuppose that capitalism is efficient.

It’s pretty easy to argue against this argument. In plenty of countries there are government owned hospitals, universities, drinking water supply systems etc. It’s pretty obvious that governments can provide goods and services, which are cheaper and better than privately offered alternatives. Up until recently I could buy my electricity from only a single source (state owned). Now, thanks to capitalists, I can buy electricity from many sellers, but all of them demand more expensive prices compared to what I had before. Communists made plenty of other mistakes that caused their economic problems (fixed prices, inability to adjust supply to the demand, stupid five year plans and so on).