In the last few months we’ve seen attempts by Kurdistan and Catalonia to gain independence. Both attempts were shot down with non-lethal but overwhelming military force. That’s clearly one difference between those break-aways and the more successful on in Crimea. These events ought to force any thinking person to ask “what is a ‘nation’?” and to wonder how nations establish their legitimacy.

There is a huge body of political philosophy around the topic of “what is a nation?” The prevailing attitudes are shaped by Locke, Hobbes, Rousseau, and their followers and interpreters. Locke and Hobbes were engaged over the topic of where the authority of the state comes from – is it force, the nature of power, divine will, or something else? At the core of the discussion is the issue of how people went from being ungoverned to governed. It appears that the question of origin of government is resolved: humans never were ungoverned. We evolved as social animals, and society, hence leadership, and thus government, evolved along with us. The thinkers of the enlightenment were still distracted by religion, with its myth of the Garden of Eden and a time where people were not in a society – a myth that is not true: there never was a “state of nature” in which man was un-led and un-governed. If you look at Rousseau’s The Social Contract in that context, he was concerned with explaining how it was that people came to accept government; how they came to voluntarily make themselves subjects.

From what we can see of some of our primate cousins, and the bones of neanderthals (and possibly austrolopithecines) it appears that one of the first things humans did was war upon eachother; it’s possible that enlightenment thinkers had things exactly backwards – war caused government; leadership was necessary because of conflict, and tribal cohesion was necessary because a solitary human was prey. Hobbes was wrong with his idea that the state of nature was “war of all against all” – solitary humans were not fully human; not politically, anyway.

Staigue stone fort, ~300AD, photo by mjr, 2004

Forts are made so that groups of humans can defend themselves against other groups; it’s a gigantic investment in resources and time to build something like that, but the alternative is worse.

While Hobbes imagines that anarchy would look like solitary humans hunting each other, he ignores the obvious fact that humans hunt in packs; we always have hunted in packs. And, with apologies to the enlightenment thinkers, those packs were proto-monarchies. Humans and government co-evolved; there never was a time when there was no organizing principle in force over groups. When do we switch from calling someone a “tribal chief” to a “ruler”? The only distinction is the number and capability (for war) of their subordinates.

Rousseau’s idea of the social contract was ground-breaking for its explanatory power, even though it was wrong about how governments came into being in the first place: he says government gains its power from the consent of the governed.

[Side-discussion: Many Americans interpret the words “social contract” as a literal contract in the modern usage of the word, as if it were a legal agreement that both parties have negotiated, accepted, or rejected. Rousseau’s use of “contract” is more like “arrangement” or “agreement” there is none of the legalistic baggage of signatures and point-by-point itemization of issues that we might assume come along with a modern contract. I mention this because often I hear people say “I didn’t sign the social contract” – which is usually short-hand for something like “I don’t agree with society’s rules or the government’s laws.” I don’t think that’s a very strong position to take against government legitimacy, and neither do governments. [stderr]]

The idea of the social contract, as an arrangement that allows people to live and cooperate under a government, is that the individual gives up some of their natural rights [per grotius] in return for the benefits of living in society. Society guarantees protection, our right to some degree of personal liberty, maybe the pursuit of happiness – and in return we agree to sometimes risk our lives to defend it, or at least pay our taxes. A cynic would say something like: “we agree to become a cog in the vast machine, in return for the machine’s guarantee that we’ll at least be periodically oiled.” A more profound cynic would argue that the arrangement is similar to that of the shepherd who guards the flock and protects them from wolves, so they can live longer wolf-free lives until the shepherd decides their wool is no longer worth shearing and turns them into mutton stew.

That original old anarchist, Epicurus, withdrew from the civilization that surrounded him, because he did not wish to be part of a government built upon compulsion or force. He didn’t opt out of the social contract entirely, because he remained a civilized man – but he built his own little society around his villa and his garden, based on no coercion at all. Naturally, had the government of Athens wished to prove Epicurus’ point, they could have sent a few troops around and encouraged them to volunteer to re-join Athenian society in lieu of a spear in the guts. That would prove Epicurus’ point but it would not be much of a victory for his little band.

Inner ramparts at Staigue fort. mjr, 2004

Epicurus and other anarchists (like: almost all of them!) bring a complaint against government that it does not have legitimacy because it ultimately rests its case on coercion. To them, Rousseau, to put it mildly, was wrong: government is not established by and for the people, in operation it is more like a gang that talks softly but carries a big stick.

Robert Paul Wolff’s argument against government is along the axis of opposing government’s collective nature against individual autonomy. Personally, I find it impeccable. How can I give up my autonomy to a government in return for its promise to protect the autonomy it demands I give up?

The language of social contract is particularly relevant today, because the dominant power in the world, the United States, is founded on a bunch of documents that indirectly reference the social contract; it was a very influential idea at the time the North American colonies declared their independence.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

Never mind that the US’ founding fathers didn’t act in accordance to a whit of what they wrote, it’s an important document that has had global influence – if only as a result of the US being the world’s superior military power. This: “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed” is a statement that the social contract is the foundation of government authority. It’s a leap from Louis XIV’s “L’état c’est moi.” “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government” – at the time Rousseau published The Social Contract, it was censored and he was threatened with arrest, because the book was a tacit approval of revolution. Since Rousseau was arguing that the divine right of kings was not the source of sovereignty, and the sovereign had to represent the people; a sovereign who did not represent the people had no legitimacy. The founding documents of the US express that sentiment: “That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government” – in other words, Rousseau had published a blueprint for revolution.

It’s a deeper cut into the authority of the state than Wolff’s opposition of autonomy and state authority, since it is contingent on the state’s behavior, not a fine point of philosophy. Anarchists who warn us that the state is founded on the threat of violence are right, but Rousseau’s charge is that the state that is not meeting its ends of the bargain is not legitimate; what is the bargain? It is to seek the general good. That’s all expressed in the form of the rule of law, the detailed bill of rights that enumerates what the citizen gets from the state in return for the loyalty they show, and the liberty they give up. And that is where I see the deep rifts forming in the nations we see, today, confronting democratic popular uprisings.

It’s a deeper cut into the authority of the state than Wolff’s opposition of autonomy and state authority, since it is contingent on the state’s behavior, not a fine point of philosophy. Anarchists who warn us that the state is founded on the threat of violence are right, but Rousseau’s charge is that the state that is not meeting its ends of the bargain is not legitimate; what is the bargain? It is to seek the general good. That’s all expressed in the form of the rule of law, the detailed bill of rights that enumerates what the citizen gets from the state in return for the loyalty they show, and the liberty they give up. And that is where I see the deep rifts forming in the nations we see, today, confronting democratic popular uprisings.

The first case is the US. Since the beginning of the red scares and the J. Edgar Hoover Federal Bureau of Investigation, the US has begun to increasingly shamelessly violate its own rule of law. We have seen tremendous erosion of the constitutional requirement for Congress to control war and the budget. We have seen violation of the 4th amendment, and the government continues to assert its unconstitutional power to inflict capital punishment. We had COINTELPRO. We have Gitmo, and drone assassinations of US citizens, approved by a classified court. The US government has stomped all over the rule of law, in ways too numerous to list – and that’s without even talking about slavery, the breaking of treaties with the Indigenous People, and the disenfranchisement of the Jim Crow period (which continues today). When you throw in things like asset forfeiture and violent, racist, policing, it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the US is a failed state; that it is not living up to its part of the social contract.

That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it

Powerful words. Lies, from a failed state.

I’m thinking of this in particular because of the Kurdistan independence vote, which was quashed with military supremacy, and the Catalan independence vote, which was suppressed by violent policing and an internal purge. The Spanish Government said the Catalan independence vote was “unconstitutional” – by which they meant there is no provision in the rule of law – but Rousseau has written them a justification for dissolving the political bonds between Catalonia and Spain. The same justification is written for Kurdistan. When the cops began to beat the protesters, the Spanish Government had tacitly admitted it had no legitimate claim to govern (else, why would the cops need to beat protesters?) and when the Iraqi Government deployed artillery and American-made M1 Abrams tanks against the Kurds they admitted they had no legitimacy to govern, either (after all, why else would they need Abrams tanks?). The razor blade hidden in Rousseau’s justification of democracy through a social contract is that most governments don’t meet the high standard that he set.

It is not good for him who makes the laws to execute them, or for the body of the people to turn its attention away from a general standpoint and devote it to particular objects. Nothing is more dangerous than the influence of private interests in public affairs, and the abuse of the laws by the government is a less evil than the corruption of the legislator, which is the inevitable sequel to a particular standpoint. In such a case, the State being altered in substance, all reformation becomes impossible. A people that would never misuse governmental powers would never misuse independence; a people that would always govern well would not need to be governed.

If we take the term in the strict sense, there never has been a real democracy, and there never will be. It is against the natural order for the many to govern and the few to be governed. It is unimaginable that the people should remain continually assembled to devote their time to public affairs, and it is clear that they cannot set up commissions for that purpose without the form of administration being changed.

In fact, I can confidently lay down as a principle that, when the functions of government are shared by several tribunals, the less numerous sooner or later acquire the greatest authority, if only because they are in a position to expedite affairs, and power thus naturally comes into their hands.

Jean Jacques Rousseau The Social Contract, book III chapter IV

It’s not quite cut and dried: the other people in a country have some interest in the fortunes of the state; if a supermajority of the population in a region vote for independence, what about the other citizens on the other side of the country? There were massive majorities for independence in Catalonia, Kurdistan, and Crimea; the rest of the countries did not have similar majorities. In other words, the rest of Spain did not agree. How do we resolve this? In Spain, the government has charged the Catalan independence leaders with sedition and rebellion and is trying to have them extradited from Belgium so that they can be punished. Authoritarianism and fake democracy continue to dominate the world’s politics.

“We are all just prisoners, here, of our own device.”

I need to note that Rousseau appeared to be arguing that the only democracy worth of the name was direct democracy – one person, one vote. Which, in Robert Paul Wolff’s analysis, is also the only democracy that has a chance of balancing the autonomy of the individual against the nation – however, Wolff argues that a direct democracy must be based on a heavy supermajority (on the order of 95%) so that there is no possibility for a “tyranny of the majority” to arise. Wolff uses that unlikelihood as a reason to disqualify direct democracy as a legitimate political system.

Rousseau was a complex man – probably he’d be diagnosed with a disorder like schizophrenia, today – full of contradictions and grudges. Contradictions: he wrote one of the first books on child-rearing, but abandoned his own offspring to a poorhouse and never met them. Grudges: he was from Geneva, Switzerland, where his father had come into conflict with a fake democracy; Geneva operated based on a political system that looked like a democracy, but was actually run by a secret “little committee” that controlled all the votes. There was no popular vote; the franchise was only available to the bourgeoisie, and even they didn’t realize their votes weren’t counted in any way. Rousseau appears to have formed a lasting suspicion of representative democracy. Rousseau would quickly recognize the US as a pseudo-democracy; his senses were already attuned to detect them.

I included the pictures of the Staigue Fort because it’s emblematic, to me, of early government. Doubtless some leaders were trying to foster the good for their people, and they built fortresses because they had to, to defend themselves. Yet, to what degree was “self-defense” their desire to preserve their own power? Kings and lords have always known what happens to defeated kings – it’s not good for them, or their people, unless they’re bad kings. The bad kings are the ones, in days gone by, who had lost the favor of the gods. War is inextricable from the state. As an anarchist, and a skeptic, I don’t see states as doing much else of importance. Neither, it appears, do they – they always keep the swords sharp so they can turn them on the enemies of the people, or the people, whichever, whenever, whatever.

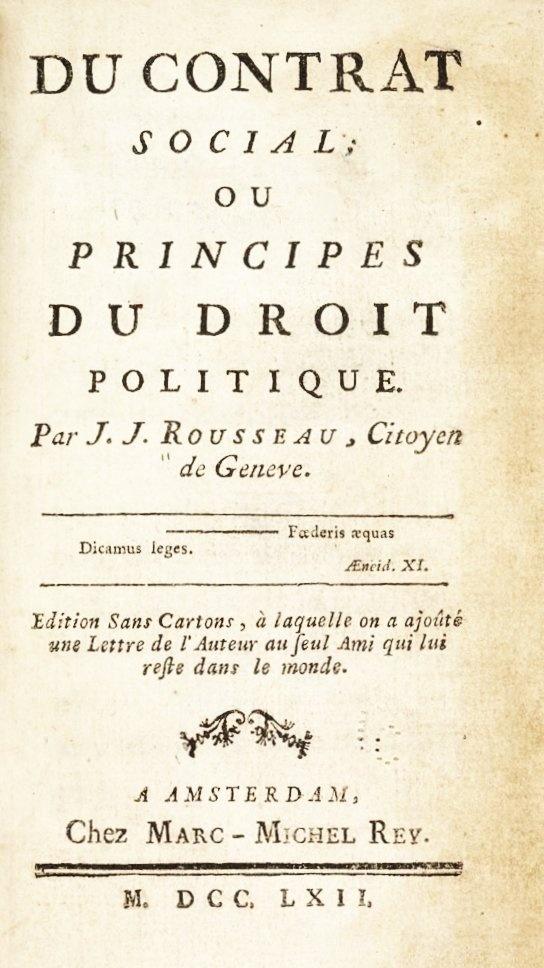

The cover of the copy of Rousseau that I included is interesting. Translated roughly, it reads:

Edition without cover-boards, with an additional letter from the author to the only friend left to him in the world.

I believe it is an 18th century bootleg.

Tangent: I’ve always thought it worth pointing out that the bible uses the “shepherd” metaphor for God/Jesus in significant places. Yet shepherds do not look after their flocks out of any kind of selfless love for the sheep. How did that metaphor ever get the positive connotation it has, given that the writers and readers must have been familiar with shearing, and mutton?

Speaking of contradictions, I’ve always thought it significant that Jefferson could use that unqualified phrase “all men” while owning men whose rights were indeed alienated. Or did he think that black men were implicitly not “real” men; that “men” implicitly meant “white men”?

Typo above in the afterward about Rousseau: “offspring offspring”

Owlmirror@#1:

I’ve always thought it worth pointing out that the bible uses the “shepherd” metaphor for God/Jesus in significant places. Yet shepherds do not look after their flocks out of any kind of selfless love for the sheep. How did that metaphor ever get the positive connotation it has, given that the writers and readers must have been familiar with shearing, and mutton?

That has always beaten the shit out of me, too. It sounds as if god is using its followers as some sort of Matrix-style prayer batteries, which only run for a short while before being discarded in the dustbin of heaven. The whole metaphor is horrible at every level and from every angle.

Speaking of contradictions, I’ve always thought it significant that Jefferson could use that unqualified phrase “all men” while owning men whose rights were indeed alienated. Or did he think that black men were implicitly not “real” men; that “men” implicitly meant “white men”?

I don’t know what Jefferson thought, but I don’t think Jefferson was anywhere near the great political philosopher some try to make him out to be. As I’ve tried here to slyly imply, much of the ringing language of the Declaration is Rousseau’s (Rousseau had a great way of putting things together) Jefferson appears to have lifted chunks of it and not examined them very carefully, cherry-picking his way to a justification for American pseudo-democracy.

Typo above in the afterward about Rousseau: “offspring offspring”

(Grabs his

Strike Pen)Afterthoughts:

I try to write these “Sunday Sermon” pieces quickly, to give them the flow of a spoken rant. Often, I’m tired or it’s late, or I’m stuck in an airport departure gate somewhere and I’m tired and it’s late. I’m not making excuses, I’m explaining. If sometimes it seems I’m meandering more than usual, that’s not deliberate, but it’s to be expected.

A topic like this requires a book-length treatment, and a library of references. I have the latter but I’m not capable or interested in producing the former. I suspect myself of confirmation bias, but whenever I find myself inclined to reject the legitimacy of the state (which is often) I reach for Robert Paul Wolff and Epicurus and there is simply no way I can contribute anything to the discussion that they have not, except for little scraps. For example, I think that some skeptical explanation of the whole “state of nature” trope is worthwhile – anthropologists should be providing it, but generally I think they steer away from political philosophy. I’m willing to be the fool that rushes in, here.

When I write these things and I am tired, I sit and hammer away while ideas bubble up like steam in a pot of marinara – sometimes they burst and vanish, other times I manage to collect them in the right sequence and add them to the piece. When I come back and read the whole piece the next day, I often think “Arrgh! I completely forgot (some piece)” So, in that spirit, here is a bit of mini-rant that I intended to fit somewhere in there, but didn’t. I think it’s a point worth reminding people of:

The purpose of a society, a nation, is – according to Rousseau – the general good. Without floundering into the swamp trying to define general good can we say that these are elements of the general good:

– Providing for common defense

– Establishing laws and maintaining a system of justice

– Protecting the weak

– Restraining the strong (implied in protecting the weak)

– Preserving order

Anthropologists seem to agree with my premise above, that human societies and tribes exist for those reasons, and probably always have, since before when austrolopithecines huddled together for warmth, or hunted together in packs. In that sense, a society, tribe, or nation, is a form of extended family. Like an extended family, we care for our fellow hunter who has broken a leg, feeding and helping them until they recover. Or we care for our ageing tribal elder, who is perhaps a repository of wisdom and wit, though their eyes have grown dim and they can no longer use a spear. Perhaps we support the unusual member of our tribe, the one who is clever with their hands and mind, who has such silly ideas like “what if we got on the back of the 4-legged runnerbeast?” or “what if I used strips of hide to attach a sharp pointed rock to the end of my throwing stick?” There are also certain communal activities that are inherently more efficient if they are done in a group: one person with a spear might bring down a deer but cannot eat or process it all single-handed before the meat spoils – the hunter shares with the tribe so that the entire tribe does not have to hunt individually. “Specialization of labor” is not how austrolopithecines would have explained it 2 million years ago, but they probably would recognize the concept.

I am arguing that the general good of a civilization includes:

– Reducing interior conflict (Justice system)

– Fostering innovation (Research and development)

– Caring for the sick and elderly (Social Security)

– Division of labor and specialization

I believe that one could probably make a good argument that division and specialization of labor is what society is all about (one specialization being military).

Now, let us step back and look at the United States of America in 2018: it is the wealthiest and most powerful nation on earth. In part, because of fortunate geography and natural resources, but also because it effectively fostered innovation, minimized interior conflict (repressively, I’m sad to say) divided labor effectively, and fostered a certain amount of sharing between the strong and the week, the well-to-do and the needy. In the last few decades, however, we have seen a scary new trend, for the top tier of society to reject the social contract. The elites (this is not a partisan issue, all the elites are doing it, it’s just a question of degree and aggressiveness) have decided:

– To have their own justice, which is more generous to them than the rest of the population

– To have a massively disproportionate share of the economic benefits

– To reduce sharing by cutting down their support for the weak and needy

– To stop scientific research and development except where it benefits them

– To bypass any form of meritocracy in favor of inherited privilege

In other words, the top tier of the United States Of America has turned against the common good, and is working only for its own good. They have become a nation of their own, a parasitic nation, with its own rules and its own economy. They have not merely broken the social contract, they have utterly destroyed. it.

Maybe. Or maybe, like Rousseau, Jefferson had a problem with proclaimed high ideals and values, and contradictory actual behaviors implied by the negation or absence of those ideals.

I might have a rant or two on that topic, at some point.

I like to imagine a wiki-based direct democracy, but I fear it would be vulnerable to Russia-type tampering.

Emu Sam@#5:

I like to imagine a wiki-based direct democracy, but I fear it would be vulnerable to Russia-type tampering.

Since the current system is vulnerable to such tampering (it always has been, first through the “representative democracy” then through the two party system, and finally through gerrymandering and vote suppression) it can’t get any worse – why not try something else? Russia-style tampering is small beer compared to what the two party system does and has always done. They’re just pissed off that the Russians got a seat at the table without paying for a ticket.

(The obvious answer is that the government will demonstrate how illegitimate it is, the second the citizens try to stand up to it)

Owlmirror@#4:

Maybe. Or maybe, like Rousseau, Jefferson had a problem with proclaimed high ideals and values, and contradictory actual behaviors implied by the negation or absence of those ideals.

That’s a fair point. It’s possible to see more clearly what we think is right because it’s not what we actually do.

Aspirational politics are a problem because we don’t generally get to see how they work in practice. We can sit mired in an aristocracy and think Marxist/Leninism sounds pretty good, but I don’t think it worked very well (though I know Marxists who’d say “they didn’t try hard enough!”)

Happy birthday, Marcus!

it’s possible that enlightenment thinkers had things exactly backwards – war caused government; leadership was necessary because of conflict, and tribal cohesion was necessary because a solitary human was prey

Not necessarily. Leadership is necessary also for the “hunter” part of the “hunter and gatherer”. As wolves and lions can attest, killing your dinner is a lot simpler when you aren’t hunting alone.

“I don’t agree with society’s rules or the government’s laws.” I don’t think that’s a very strong position to take against government legitimacy, and neither do governments.

“I don’t agree with society’s rules or the government’s laws” is a weak argument against state legitimacy. “I and majority of other citizens don’t agree with society’s rules or the government’s laws” is the strongest argument there is. Unfortunately governments can choose to not care, because they have gunpowder.

it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the US is a failed state; that it is not living up to its part of the social contract

Of course. I wonder whether on our planet we actually have any states which aren’t this, which are living up to their part of the social contract. I’d say we have the same problem for every country in existence, the only difference is in degree. For example, Sweden is doing better than USA which is doing better than North Korea.

I see Kurdistan and Catalan situations very differently. Independence is pretty much the only decent option when you are oppressed by tyrannical regimes. But when it comes to Catalonia, they are part of a relatively decent country, they have autonomy, their language is has an official status, they can freely express their culture (whatever “culture” even means). So the inevitable question is what their problem is.

OK, I might accept that you don’t need any “problems” like oppression; majority of people living in any region should have a right to leave some country and make another one even if the larger country was utopian.

But it’s not that simple with Catalonia. 92% of voters in favor of independence might sound convincing, but that’s only before you realize that the voter turnout was only 43%. And these 43% of voters are definitely not representative. Before the referendum opposition parties (who are in favor of staying with Spain) urged their voters to boycott the referendum. Opinion polls (which are a lot more representative than a boycotted referendum) suggest that the number of people in favor and opposed to independence is close to 50/50. So we don’t even know what the majority of population wants.

Such a close result means that if there was another decent referendum (without boycotts of the opposition and without police crackdowns), the result would be determined by swing voters who have no strong opinion about the issue and who could get swayed by politician rhetoric.

And politician rhetoric is a whole different problem. One of the main arguments in favor of independence revolves around money. Catalonia is one of Spain’s wealthiest regions. Taxpayers send a lot of money to Madrid and they get back less. So people feel like Madrid is ripping them off. Sounds simple — just get independence and you’ll have more money. I suspect that all those people talking such bullshit fail to understand the basics of economy. Majority of Catalan exports are to other Spanish regions and to other European Union countries. If Catalonia became independent in such a way that pissed off Spain, they would lose their export markets (Catalonia wouldn’t automatically get an EU membership and Spain could put a veto on Catalonia joining EU). Moreover, whenever some region faces political instability, some businesses relocate. And the region loses investments. “Get out of Spain, get richer quickly” scheme wouldn’t work for Catalans, instead it would end up with the exact opposite consequences. So the question is whether voters even understand the full consequences of independence (the same question I kept wondering about during the Brexit vote).

By the way, I have no opinion about whether Catalonia should become independent. I also know reasons in favor of independence. For example, police brutality and persecutions of Catalan politicians. My point was that I don’t think that this whole Catalan question is so simple. So I wouldn’t equate Catalonia with Kurdistan. And Crimea was yet another totally different situation.

When the cops began to beat the protesters, the Spanish Government had tacitly admitted it had no legitimate claim to govern (else, why would the cops need to beat protesters?)

Yes, I can agree on that one. Shortly after the referendum I participated in a debate tournament where one of the debate topics was about Catalan independence. Sides were decided by a lottery and I had to argue against Catalan independence. Back then that seemed like an easy position to defend. But now after all those stupid things Spain did I’d probably prefer to argue in favor of Catalan independence.

There were massive majorities for independence in Catalonia, Kurdistan, and Crimea;

Not really. I already addressed Catalonia, even if there’s a majority, it’s anything but massive. And in Crimea this wasn’t about independence, it was about leaving Ukraine and joining Russia. And there was some ridiculously serious voter fraud going on. That so called “referendum” was a fucking joke. Russia employed pretty much every vote rigging and ballot box stuffing technique there is. And all the vote rigging was well documented. And even the ballot papers themselves were ridiculous. On the ballot papers voters had to choose between two options and none of those options was about maintaining the status quo within Ukraine. That referendum was just a farce, you cannot take it seriously as representing the desires of Crimean people.

OK, I know opinion polls suggest that majority of people living in Crimea actually wanted to join Russia. So probably a legitimate and correctly conducted referendum would have given the same result. But I still have a serious problem with all that vote rigging that is going on in every election in Russia. To paraphrase your words: “When Putin began to rig votes in every election and referendum, he had tacitly admitted he had no legitimate claim to govern (else, why would Putin rig votes?)”

the rest of the countries did not have similar majorities. In other words, the rest of Spain did not agree

I’d say this is irrelevant. People living in other regions should have no say about these questions.

War is inextricable from the state. As an anarchist, and a skeptic, I don’t see states as doing much else of importance.

Healthcare, education, public transportation, infrastructure, legitimate protection from crimes (like theft, murder etc.), protection of nature, regulating corporations and limiting their greed, helping the disabled, elderly, unemployed, orphans and so on. Oh, and some countries actually give money to artists and pay for art museums. So I’d say that states have a lot of important functions.

I liked Robert Paul Wolff’s book. I can agree with his arguments that states aren’t legitimate. But that doesn’t change the fact that after agreeing that states suck we are still left with all those pesky practicalities, for example, how do we educate children born in poor families without a state which pays for their education.

whenever I find myself inclined to reject the legitimacy of the state (which is often) I reach for Robert Paul Wolff and Epicurus and there is simply no way I can contribute anything to the discussion that they have not, except for little scraps.

I reject the legitimacy of all the states we have on this planet. Not just often, but all the time. There are problems inherent in the very core of how a representative democracy is supposed to function. Even if we lived in a perfect representative democracy (the wealthy not abusing their money, the leaders actually caring for people and so on), I still would see it as illegitimate. Still, I don’t consider myself an anarchist. Whenever I read authors arguing against the legitimacy of the state I’m always confronted with the same problem. My response goes approximately, “Duh, of course our states are illegitimate; you don’t have to try to convince me about that. Now that we have agreed about states being illegitimate, let’s tackle the real issue — how do we make something different, something better, something that would be legitimate? We need some system, some institution that fulfills human needs like healthcare, education, protection for the weak and disadvantaged and so on.” So far I haven’t read any anarchist able to demonstrate how any alternative system could actually work and fulfill these needs. So I’m stuck with accepting all our shitty and illegitimate states as necessary, because we just cannot live without them. The only thing we can possibly do is try to make some minor improvements in order to make our real life representative democracies closer to what would be an ideal representative democracy — reduce corruption, stop things like gerrymandering, tax the rich, increase welfare payments for the poor and so on.

I’d agree with Ieva Skrebele – your position is hardly surprising, given that you live in a failed state. Try living somewhere where a broken leg wouldn’t bankrupt you, where university education is free, and where trains are worth having and just work. It might adjust your opinion.

Nothing to add to the debate as what I would have added has already been said, but Staigue Fort is amazing isn’t it?

I agree that some kind of government is pretty much inevitable for humans as long as we’re a social species. That’s an interesting position for an anarchist to take, though!

When it comes to governments, I tend to be a pragmatist. Sure, one can always come up with philosophical reasons why governments are not legitimate, but in practice they’re always going to exist, so the real question for me is how well they do at creating the conditions for a good life for their citizens. Answering that gets very complicated because people disagree about what a good life even is.

jazzlet@#11:

Staigue Fort is amazing isn’t it?

It really is. The design is very simple but very effective. I didn’t get a decent picture of the entry, but it’s designed so that you can only get through by bending over, which means you’re basically helpless to defend yourself. 2 or 3 people could hold the entry on the inside against an army. The rocks are laid so tightly together, it’d be hard to climb (I tried, but not seriously)

If you want to see a really amazing Irish iron-age fort, check out Dun Aengus. I was going to visit there in 2012, but the weather was awful and nobody in Galway wanted to take a boat out. Then, when I looked at the water, I didn’t want to go in a boat.

Dun Aengus, “when retreat is not an option.”

springa73@#12:

I agree that some kind of government is pretty much inevitable for humans as long as we’re a social species. That’s an interesting position for an anarchist to take, though!

It’s a painful one, for me. In principle I think all governments are corrupt and violent, but (I suppose that’s the point of this piece – if it has one) civilization and government are the necessary conditions for each other. Rousseau, in his eagerness to argue against the authority of illegitimate government, imagines that man, in a “state of nature” lived a sort of edenic existence. Anthropology appears to show that Rousseau was, as he often did, making stuff up.

When it comes to governments, I tend to be a pragmatist. Sure, one can always come up with philosophical reasons why governments are not legitimate, but in practice they’re always going to exist, so the real question for me is how well they do at creating the conditions for a good life for their citizens. Answering that gets very complicated because people disagree about what a good life even is.

Agreed.

While we’re waiting for the moral philosophers to plug their moral facts into their moral calculus and tell us what the good life is, I believe we should restrict government’s power – not necessarily “little government” but maybe “weakened government” – I don’t care if I have Big Brother as long as Big Brother is a moron.

Ieva Skrebele@#8:

Leadership is necessary also for the “hunter” part of the “hunter and gatherer”. As wolves and lions can attest, killing your dinner is a lot simpler when you aren’t hunting alone.

I divide “leadership” from political power, because leadership is usually contextual and temporary. It becomes political power, even government, when it decides to preserve itself and assert its authority whenever it can. In other words, if we go hunting and you lead (because you are more skillful) you’re not trying to maintain power and authority over me – you’re just doing what is most efficient in that context. If you then tell me “I am the hunt-leader and I say you should not eat the snozzle-berries!” then it’s attempting to extend leadership into authority.

“I don’t agree with society’s rules or the government’s laws” is a weak argument against state legitimacy. “I and majority of other citizens don’t agree with society’s rules or the government’s laws” is the strongest argument there is. Unfortunately governments can choose to not care, because they have gunpowder.

A case in point: a plurality of citizens in this country do not agree with the War On Drugs, because they smoke weed anyway. They do not agree with national speed limits because they break them all the time. Etc.

I don’t agree that saying “I don’t agree with society’s rules” is weak. If I have any autonomy at all, then I ought to be able to stand opposed against the rest of my civilization. For who is to say I am wrong? (if it is a matter of opinion) And, naturally, the final argument of kings applies: might makes right. But, that’s just authority. If the state asserts its authority against me with force, then it’s an occupying power – as Robert Paul Wolff points out: I am wise to obey coercion but I owe no obedience when the coercer turns their back. I’ll observe that a lot of people act that way, in many small ways: they reject society’s coercion in favor of their own autonomy.

I wonder whether on our planet we actually have any states which aren’t this, which are living up to their part of the social contract. I’d say we have the same problem for every country in existence, the only difference is in degree. For example, Sweden is doing better than USA which is doing better than North Korea.

It appears to me that Sweden (I have spent some time there) and Norway (as another example) show a commendable concern for the common good; they seem to me to be some of the most legitimate states on Earth. Naturally, they may engage in coercion when necessary (ask Anders Brievik) but, again, the focus seems to be on the common good. In the US, the focus is on the good of the 1/10% and their minions in the 1%. In North Korea, the common good appears to extend to the Kim family and close hangers-on.

But it’s not that simple with Catalonia. […] So we don’t even know what the majority of population wants.

True. I infer from the use of armed riot police against civilians that Spain isn’t particularly interested in learning what the majority of the population wants.

To me it gets complicated – so complicated I have no idea what I think. For example, Catalonia became part of Spain under Franco; so it’s part of Spain by right of conquest…? It seems that the Catalans could fairly easily argue that they were a separate state until they were conquered (variously by France, Spain, the moors, etc) and that occupying powers may come and go but they are not owed any loyalty. That doesn’t appear to be the tack the Catalans were taking, they seemed to trust the EU’s words about “democracy” perhaps too much.

My point was that I don’t think that this whole Catalan question is so simple. So I wouldn’t equate Catalonia with Kurdistan. And Crimea was yet another totally different situation.

Fair enough. I am equating them only to the degree that there were popular referendums of some degree or another, with all the fol-de-rol of democracy sprinkled about until authoritarian regimes decided to step up and show that Rousseau was talking through his hat.

And in Crimea this wasn’t about independence, it was about leaving Ukraine and joining Russia. And there was some ridiculously serious voter fraud going on. That so called “referendum” was a fucking joke. Russia employed pretty much every vote rigging and ballot box stuffing technique there is. And all the vote rigging was well documented. And even the ballot papers themselves were ridiculous. On the ballot papers voters had to choose between two options and none of those options was about maintaining the status quo within Ukraine. That referendum was just a farce, you cannot take it seriously as representing the desires of Crimean people.

Agreed.

But, what else is there? I’m OK with saying “let’s wash our hands of democracy, that bullshit doesn’t work.” Because it does not appear to work.

One nitpick: saying ‘we want to leave this country and join that country” would be an act of achieving independence (if it were done democratically) because first there is “leave” then there is “join” and one must have the independence of leaving to have the independence to join.

In Crimea, it’s a moot point. I put Crimea on that list because its an example of how bogus the process can be. I could have as easily pointed to Kosovo.

I still have a serious problem with all that vote rigging that is going on in every election in Russia. To paraphrase your words: “When Putin began to rig votes in every election and referendum, he had tacitly admitted he had no legitimate claim to govern (else, why would Putin rig votes?)”

Agreed. And I like your paraphrase.

I’d also argue that any election in which it is necessary to vote-rig, vote-suppress, or propagandize the people cannot result in a legitimate state. After all, if one needs to lie to the people, or manipulate their vote, or fool them – then one is admitting in advance that one knows one doesn’t reflect the popular will.

I am not defending Russia at all. It’s one of the big three pseudo-democracies that dominate the world right now. (Well, the Chinese don’t exactly bother to pretend very much)

I’d say this is irrelevant. People living in other regions should have no say about these questions.

I think they do, to some degree, as it may affect them. Of course it’s complicated. Iraq is an example: the Kurdish zone has been part of Iraq for a longish while. But there’s a lot of important oil there. So if they declare independence they are whacking great chunk out of the rest of the Iraqi economy. We can’t just have any old ethnicity declare independence around an oil field or a gold mine – it does affect the rest of the country.

I don’t know how to answer that question except that I think that we can analyze the way regions entered into a nation. For example, if California wanted to secede from the US and return to Mexico, I think they’d have a better case than if they wanted to secede from the US and just take half of the US economy along with them. California was taken from Mexico by force of arms; but since they haven’t exactly been fighting an anti-US insurgency since that time, I don’t think they can fairly say they want to treat the US as an occupying power.

As someone who sees nationalism as a great big lie, trying to think this stuff through makes my head hurt. It doesn’t make sense and it never made sense.

Healthcare, education, public transportation, infrastructure, legitimate protection from crimes (like theft, murder etc.), protection of nature, regulating corporations and limiting their greed, helping the disabled, elderly, unemployed, orphans and so on. Oh, and some countries actually give money to artists and pay for art museums. So I’d say that states have a lot of important functions.

Sure! I didn’t break my list down to that fine a level of detail because I was trying to keep my description of “the common good” at the basic level of common goods without which we haven’t even got a civilization. A civilization that can’t preserve order doesn’t get around to building hospitals or roads or art museums. Nor does one that is unable to defend itself from predatory nations, and gets conquered. I would say those things are extremely desirable parts of the common good, for sure. The big items are the ones without which you haven’t got a state.

Put differently: Somalia is a “failed state” because they cannot preserve order, not because they don’t have art museums. Actually, they don’t have art museums because you can’t have art museums if you cannot preserve order.

I liked Robert Paul Wolff’s book. I can agree with his arguments that states aren’t legitimate. But that doesn’t change the fact that after agreeing that states suck we are still left with all those pesky practicalities, for example, how do we educate children born in poor families without a state which pays for their education.

I agree with that, though if we were to say that offering equal education for the poor was one of the common goods required to be a legitimate state, there are very few legitimate states on Earth. I guess I was deliberately keeping the bar low at “preserve order” and such. Education? Argh, the US has re-segregated its schools very effectively but stealthily. I’ll believe I’m seeing equal education in any country when I see no private schools attended by mostly kids of wealthy parents, and a few tokens.

Ieva Skrebele@#9:

I reject the legitimacy of all the states we have on this planet. Not just often, but all the time.

Me too. It’s why I call myself a “post nationalist.” I do not believe the nationalism system results in governments worth having. In a few cases it results in governments that look great when compared to the worst of the lot. But ultimately governments try to offer us hobson’s choice, or a boot in the face.

We need some system, some institution that fulfills human needs like healthcare, education, protection for the weak and disadvantaged and so on.” So far I haven’t read any anarchist able to demonstrate how any alternative system could actually work and fulfill these needs.

Agreed. I think the situation is worse than that, even. Take, for example, Leninist Russia post-revolution. The leninists screwed it up pretty horribly (as did Mao in China) but it appears clear to me that even if they had created a workers’ paradise, the capitalist oligarchies that ran the rest of the world would not have allowed them to succeed. So, things like education and healthcare are down on the list after somehow protecting against predatory other nations. That is why I don’t think anarchism will work in practice: the Athenians can always march a few hoplites down to Epicurus’ farm and poke them with spears until they rejoin the body politic.

Here’s a shitty scenario: an anarchy might work if they had weapons of mass destruction that could keep predatory nations at bay. But that’s negative liberty, not positive liberty (per Isaiah Berlin) and I don’t think one can build a legitimate state by threatening everyone else with destruction.

The only thing we can possibly do is try to make some minor improvements in order to make our real life representative democracies closer to what would be an ideal representative democracy — reduce corruption, stop things like gerrymandering, tax the rich, increase welfare payments for the poor and so on.

That brings us right back to that evil motherfucker Winston Churchill’s “it’s not the best form of government, but it’s better than the others.” I do believe that if enough brain-power were applied, we could come up with significant patches to democracy – make it much much better than it is. There has been very little effort expended (other than by Rawls) in trying to devise better ways to build democracies. That’s, rather obviously, because the psudodemocracies that run the world don’t want anything like that; it would disempower their rulers and we can’t have anything like that.

When do we switch from calling someone a “tribal chief” to a “ruler”?

When they’re white. Bleh. See also, “Tribal Warlords”. We all know which area of the world the news commentator’s talking about.

We pretend that the government is legitimate because we’d rather not have a demonstration of illegitimacy. This –> But ultimately governments try to offer us hobson’s choice, or a boot in the face.

I’m privileged enough to be left to live my life as I choose without daily brutality and direct oppression. Sticking my head in the sand and just living my life is complicity and aggression against people who don’t have that luxury.

I don’t agree that saying “I don’t agree with society’s rules” is weak. If I have any autonomy at all, then I ought to be able to stand opposed against the rest of my civilization.

OK, I’ll accept that.

Still, I would never say that “I don’t agree with society’s rules”, because that sounds like an “argument” a child would use in a discussion against their parents. Instead I would opt for “the existing society’s rules are harmful/unfair etc., therefore they should be changed”.

It seems that the Catalans could fairly easily argue that they were a separate state until they were conquered (variously by France, Spain, the moors, etc) and that occupying powers may come and go but they are not owed any loyalty. and I don’t know how to answer that question except that I think that we can analyze the way regions entered into a nation. For example, if California wanted to secede from the US and return to Mexico, I think they’d have a better case than if they wanted to secede from the US and just take half of the US economy along with them. California was taken from Mexico by force of arms; but since they haven’t exactly been fighting an anti-US insurgency since that time, I don’t think they can fairly say they want to treat the US as an occupying power.

I have a problem with this line of reasoning. I know that it is used extremely often whenever people in some region are dissatisfied with being part of whatever country, but this argument is just so problematic. And you can use it to prove pretty much anything. “One hundred years ago region X was part of country Y, therefore also today it should be part of country Y. But wait, two hundred years ago region X was part of country Z, therefore X should belong to Z. No, three hundred years ago X was an independent country, therefore X should be an independent country also now.” WTF? Who cares what sort of political institution people had in this region several centuries ago? What matters is what people currently living in this region want rather than how their long dead ancestors lived. This is just a form of argumentum ad antiquitatem logical fallacy. And historically all borders on maps were drawn based on which king’s army went how far. Or based on which princess married which prince thus joining their kingdoms. Or which king had two sons thus separating the kingdom.

In 1918 both Russia and Germany were weak, people living in Latvian territory decided that they don’t like being part of any of these countries, seized the chance and made a new country. The problem was that historically there had never been anything remotely similar to a Latvian country. So in order to make the new creation appear more legitimate, history was “interpreted” and new mythology got invented. Since 13th century Latvian territory was controlled by Germans, Poles, Swedes, and ultimately Russians. Before 13th century there were only multiple rivaling tribes who lived in territory that had very different borders than current Latvian country. Of course these tribes had different languages and they didn’t always get along very well (that’s why German crusaders could successfully conquer the region). This didn’t make a good origin story. The newly made country needed a better story, thus actual history got reinterpreted. Leaders of all these small Baltic tribes were turned into kings. The fact that these tribes didn’t always get along was forgotten. The fact that they spoke different languages was ignored (the word “dialects” got used instead). And somehow this stupid story about Baltic kingdoms who supposedly existed 700 years earlier and where people lived in utopian conditions without all the evil Germans and Russians was supposed to make 20th century Latvian country more legitimate. WTF? Why do people even seek such bullshit stories? What mattered were the wishes of people currently living in the region.

I think they do, to some degree, as it may affect them. Of course it’s complicated. Iraq is an example: the Kurdish zone has been part of Iraq for a longish while. But there’s a lot of important oil there. So if they declare independence they are whacking great chunk out of the rest of the Iraqi economy. We can’t just have any old ethnicity declare independence around an oil field or a gold mine – it does affect the rest of the country.

The logical extreme of your example would be a millionaire who buys a private island, discovers oil underneath it and decides to declare independence, because he doesn’t feel like sharing the oil revenue with other citizens of the country. Of course I wouldn’t be OK with that. But where do we draw the line? At which point do people have a duty to share their natural resources with their neighbors?

I’m very willing to accept the idea of solidarity. People who happen to live on top of natural resources should share their wealth with other people who happen to live in resource poor areas. That increases the overall wellbeing for humanity. But if we enforce solidarity, I really want to see consistency.

A quick glance at the Middle Eastern map will reveal that there are a bunch of small countries which are literally sitting on top of oil fields. How comes that, for example, Qatar has no duty to share their old revenue with all the people who live in neighboring regions and are poorer? Kurds have a duty to share their oil fields with the rest of Iraqi citizens. Qatar has no duty to share their old fields with their neighbors. Why? Because of those magical lines drawn on a map. Qatar is a separate country, so they can keep all their oil fields. Iraqi Kurds don’t have a separate country, so they must share. Why? What’s so magical about those arbitrary lines drawn on a map?

I like to keep my opinions consistent. If solidarity ought to be enforced, then it ought to happen always not just when it’s beneficial for whoever has the largest military. Saying “Kurds cannot leave now, because that would make the rest of Iraqi citizens poorer” enforces past land grabs. Just how did Kurds end up in Iraqi territory to begin with? This can lead to “two hundred years ago X invaded your land, therefore now X’s opinion should be taken into account when deciding about what happens with the oil fields above which you live”. I see this whole argument just as a fig leaf for “I have the biggest military, therefore I decide”.

In case you haven’t already noticed, I don’t know what my opinion about all this mess is. I see logical reasons for different positions and I’m not sure which arguments seem more important for me.

I’ll believe I’m seeing equal education in any country when I see no private schools attended by mostly kids of wealthy parents, and a few tokens.

That’s pretty much what we have in Latvia. Yeah, private schools do exist, but there are only few of them. They are either religious schools or they are some experimental weirdness (for example, there’s one Waldorf school https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waldorf_education ). All the best and most prestigious schools are state schools. The problem is that some state schools are better than others. Firstly, the amount of money each school gets depends on how many children they have, because state gives schools a fixed amount of money for each child they educate. A school with 1000 children gets five times more money than a school with 200 children. In the countryside with low population density schools are generally small and thus underfunded. Another problem is the human factor, because some schools just happen to have better teachers. I attended one of the most prestigious schools in the whole country. For example, my history teacher wasn’t just an excellent teacher, she was also the author of our history textbooks. My mathematics and physics teacher was very good too, she routinely sent her pupils to international olympiads.

It’s similar with universities. All the best universities are state owned. Private universities exist, but they are generally seen as diploma stores. Students who are too lazy to study in a state university just pay money to some private university where they can get a pretty paper without having such strict requirements for decent academic performance.

Anyway, school children have to attend whichever school happens to be closest to their home. Very determined rich parents can game the system by renting/buying a home next to the best school. Poor parents can only live wherever they can afford to. State universities accept students based on their results in standardized exams. Each study program has a fixed amount of maximum available study places. If too many potential students apply, the ones with the best exam results get accepted. Rich parents can more easily hire private tutors for extra lessons to ensure that their kids do well in the standardized exams. So it is possible for rich parents to ensure that their children have better chances within the system. But, frankly, I cannot think of any better system where the rich couldn’t just throw money at a problem. You cannot forbid parents from choosing to live next to their chosen school, nor can you forbid parents from hiring private teachers.