They also may not. Either way, if I do manage to post, I almost certainly will be avoiding any topics except those related to what I’ll be doing (unless something really captivating occurs, like Trump gets arrested, or Benghazi!) I’m going to be heading out to Bend, Oregon (vicinity) on the 1st, working on a childhood dream.

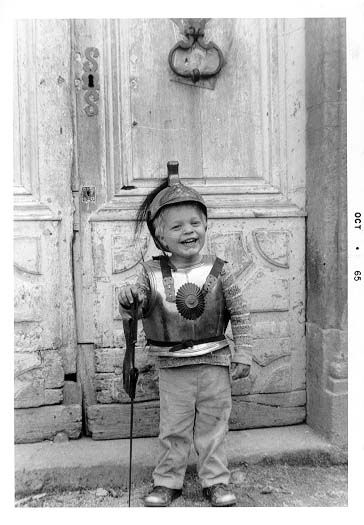

Photo by Patricia Ranum, 1965? I was 3.

When I was a kid, I saw Seven Samurai. After that, I knew what I wanted to do: I wanted to carry a sword of justice, to defend the weak against the oppression of the strong. That was before I started to think and realized that it’s all a lot more complicated than that, and that justice doesn’t come from the tip of a sword. But I was interested in swords even before then; when I would go to the Metropolitan Art Gallery in NYC I was terrified of the great big armored knights in the arms room, but I loved the swords. I have no idea, at all, why I loved the swords; there’s something about the purity and necessary practicality of the design, I think. And the simplest and most practical swords (other than the smallsword) were the samurai swords. I recall making a wooden sword as a kid; mine didn’t have a cross-hilt like a crusader’s sword, it had the round tsuba and clipped boshi (tip) of a Japanese katana. I wish I knew why I was so interested, but I was. There are dozens of swords in my house and I’d be hard-pressed to even count the knives.

My parents are pacifists so I’m pretty sure they were perplexed by me; I blame them – naturally – for hauling me to too many museums with medieval art, which is about religion, warfare, worship of power, and precious little else. When I started building things, I built working catapults (based on a design from Asterix comic books!)

Heavy weapons research; ever the sniper

I could actually put a marble onto a target at about 30 feet with that thing, with remarkable accuracy. My tin soldiers suffered endless bombardments and futile last stands; the sand dune where I used to play was endless reenactment of Fort Zinderneuf from Beau Geste and meanwhile, in the real world, the battles of Khe Sanh and Hue were raging. I was sheltered from the real world by my parents, who tried not to be over-protective, but were legitimately concerned.

Somewhere in the early 70s I got my hands on a low-powered bench grinder and made my first knife, which was of the type “prison shiv” ground out of a Solingen steel butter-knife into a wicked double-edged thing that was razor sharp and needle-pointed. I promptly dropped it onto the arch of my bare foot, where it stuck, quivering, and left a mark I still carry. That was the first of many accidental blade-marks. I probably should have been discouraged.

Around the time I got into high school, I began reading about Japanese swords; I read Stone’s Glossary of the History and Decoration of Arms and Armor and Turnbull’s The Weapons of the Samurai and concluded: “nope.” Making swords in the Japanese manner was simply out of the question because the techniques were – at that time – unpublished and closely held by Japanese crafters locked into an apprenticeship system. To learn how to do that stuff, one would have to invest most of an adult lifetime researching it and refactoring the techniques to modern tools. So I pretty much gave up on that idea; I’ve done a few knives since then, mostly stock removal, including one fancy sword-and-sorcery looking dagger that was impressive enough that I traded it 1:1 for my first motorcycle in 1982. Admittedly it wasn’t much of a motorcycle.

Since then I’ve mostly restricted myself to occasionally re-shaping and mounting machine-made (mostly CNC-cut) blades that are inexpensive in high quality from China.

oiling the handle

When I was at TomCon in Chicago a few months ago, Mike Poor pulled a credible-looking wakizashi blade out of someplace, and passed it around. He’d made it at a workshop he’d attended in Oregon, taught by a fellow who’s been doing welded steel metallurgy for several decades.

So that’s what I’m going to be up to next week. I have no idea what to expect other than that it will involve hot metal, hammers, and a lot of listening and taking notes. It’s hard for me to not approach this with a lot of crazy over-ambitious ideas; I have to work at a practical level and not fail by experimenting until I have some of the basics down.

It’s a bit intimidating and a bit of a bummer because I’m at the point in my life where arthritic joints may not really be too keen to take the impact of a steel hammer on an anvil. I’m not going to jump headlong into anything, which also means that I won’t have the kind of wild energy that I used to. I’m not as stupid as I used to be, either – the 20 year-old Marcus probably would have set himself on fire several times; I’ve learned caution and I think that’s good. When I was doing viking reenactment/SCA stuff in college, one of the guys who hung out on the fringes of the group went on to do good work as a swordsmith, and has made some lovely blades; mostly I remember the burn-marks on his hands from where he experimented with using too much flux and too high a welding temperature. I think that being older and a bit more familiar with the pain of screwing up, is going to help me listen and think and move deliberately.

I’m really excited to be trying this, though – it seems like a good opportunity to experiment using someone else’s gear and without as much of the “error” in trial and error. I don’t know how much time or energy I’ll have, and whether I’ll be part of a group that winds up dining and hanging out, or just going our own way at the end of the day. I’ll be taking camera and laptop and some remote controls and a tripod and I have no idea if I’ll be allowed to do any photography or not. So there’s a chance that you are going to be getting the blow by blow (if not every hammer-stroke) and there’s a chance I’m just going to go radio silent.

Sounds like the coastline near Bend is also really beautiful, and I’ll have a rental car. It’s oh so tempting to haul along a drone and a few more cameras… No, wait “keep it simple!”

Mostly, I’m worrying about getting my safety gear correct. This morning I went in to Clearfield to the nice folks at T&D Fabricators and collected some of the stuff that will hopefully help me keep my eyes in my head, and my fingers on my hands. I’m probably not taking the radiation meter (the orange thing in the picture) but it’s tempting – I’ve often wondered how often craft-workers wind up using re-purposed steel from Chernobyl or other places.

This is going to be a good mental break for me; the last 7 months have been a swirling toilet-bowl of awfulness and I’ve been thinking about and writing about a lot of things that I probably would be better off ignoring. I’m going to get a bit selfish and do my favorite thing: learn. Oh, the sweet, sweet feeling of learning.

I’m also taking a few books along, which I have been meaning to read or write about. But I’m going to leave the textbooks on eugenics at home, because I just don’t want to have that crap swirling around in my brain while I am trying to concentrate.

Chernobyl steel – I visited Chernobyl and Pripyat back in 2011 before the area was opened up for tourists (I.e.: when it was still edgy and hip to do so). One of the things I noticed everyplace was that “recyclers” had been at work: all the copper was gone from the nuclear reactor buildings. Did it get eaten by copper-eating bacteria, or did it get recycled into inexpensive wire sold all over Europe? Many many vehicle components were missing: transmissions, engine blocks, fuel systems, alternators – there are people driving around with mildly radioactive stuff and they don’t know it. There are huge amounts of steel – rebar, pipe, gigantic coolant pipes – that appear to have been cut out and some are stored, some evaporated. I’m a professional paranoid (and also curious) so when I encounter a piece of pattern-welded damascus steel in someone’s hand, I wonder if it’s a piece of an American Liberty ship, or a piece of a nuclear reactor.

Stacks of former water-pipe, now toxic, the vehicle graveyard, Chernobyl. mjr, 2011

Im from Portland Oregon. Bend is a many hours long drive over the cascade mountains, then through the Willamette valley, then over the Coastal mountains before you will get near the coast. At least four hours one way. But worth the trip if you’ve not been to the Oregon coast. Sounds like a good time learning some blacksmithing skills.

StonedRanger@#1:

I’m flying into North Bend, so I won’t be doing much driving up and down the coast. I do have some slack-time in my schedule so I hope I’ll be able to look around a bit. I’ll be staying in… Um.. The Metropolis of Bandon.

If anyone’s interested, the classes are here

I’m psyched but I’m worried about my joints. This may not be the retirement hobby for me.

Pack some good elbow and knee braces! It sounds like a blast; I share your obsessive love of all things sharp, shiny, pointy and dangerous. I have many many myself.

BTW, you were disgustingly cute when you were a sproglet.

The reason I recognize Bend, Oregon (I’ve never been there):

https://www.deschutesbrewery.com/

Keep an eye open on how other oldies use their hammers. There are ways of hammering without stressing your joints, and of course not all hammers are created equal. I got told off severely once by a veteran hammer wielder for having a hammer with a steel pipe handle, because I was sick of breaking cheap wooden handles. There’s as much art in a good hammer as there is in a good sword. A good hammer will vibrate in a way where the node is exactly where you hold it meaning you feel hardly anything. A well designed modern hammer with a fibre composite handle is a joy to use but costs quite a lot.

I also loved swords ever since being a child. My fascination with them started after reading Alexandre Dumas’ “The Three Musketeers”. The 10 years old me liked the idea of exciting adventures and I even fantasized about living in a world where such adventures were possible. Back then I was also too young to realize that every human culture in which swordfights existed was also extremely misogynistic and I happened to have the wrong (aka female) body.

Some years later I signed up for fencing classes. I loved them. Unfortunately, my mother tried really hard to make me quit. Ultimately she prevailed, because I ran out of pocket money savings to pay for the lessons. My mother’s problem was that I occasionally got bruises. Unlike a foil, an épée had a stiffer blade, which didn’t bend that much on impact. With protective clothes and blunt blade tips serious injuries were impossible, but bruises were pretty common. Back then my mother still hoped that she will succeed in forcing me to look and behave like a proper lady. It took her few more years to give up on that dream.

So there’s a chance that you are going to be getting the blow by blow (if not every hammer-stroke)

I would certainly be interested in that.

I’m a professional paranoid (and also curious) so when I encounter a piece of pattern-welded damascus steel in someone’s hand, I wonder if it’s a piece of an American Liberty ship, or a piece of a nuclear reactor.

This reminds me of a Russian documentary I once watched. It featured multiple people who accidentally found out that they owned some really radioactive stuff. There were some people who had a chunk of Cobalt-60 buried underground in their backyard. It was found accidentally when one curious guy who worked in a bank decided to borrow and take home his radiation meter.

There was also a Russian photographer who was informed by airport security guards that one of his camera lenses was very radioactive. Using that lens for a single day exposed him to what would be normally annual average dose of radiation. Unfortunately the documentary didn’t say who made that lens. I couldn’t recognize the manufacturer; I could only tell that it looked like one of those older manual focus only lenses.

So I’d say that paranoia is to some extent warranted. Such incidents happen very rarely though.

@Ieva before the plane starts taxiing:

I have some pictures of the radiation emitted by that stack of pipes. It was about 80/mseivert/hr Background at my kitchen at home was about 2. Background outside reactor #2 was 24. I don’t know what’s dangerous and what’s not but I think that particular steel is “nope.”

The photographer who shot footage from a helicopter down into the exploded, open, core – he died of radiation poisoning. I wonder where that lens went…

The photographer who shot footage from a helicopter down into the exploded, open, core – he died of radiation poisoning. I wonder where that lens went…

Most likely it was properly disposed of. Or, more precisely, it was stored in some place where it won’t be near any humans. You can’t really “dispose of” radioactive stuff, you can only store it somewhere.

In Russia there is a government agency responsible of disposal of radioactive stuff. That photographer with a radioactive lens gave it to that agency. And, whenever contamination is detected in some location, government will send people for cleanup. In Russia there is a law that anybody who gets exposed to radiation gets free healthcare afterwards. So the government is pretty interested in not letting radioactive stuff pile up in the wrong places.

The problem is that there are some greedy people who knowingly collect radioactive stuff and then sell it to some unlucky person (like those “smart” guys who picked up free metal in Chernobyl and sold it for scrap metal, I’m pretty certain they didn’t keep it for themselves).

And what about the pilot?

and the helicopter?

# 6 Ieva Skrebele

one curious guy who worked in a bank decided to borrow and take home his radiation meter

Ah, why does someone working in a bank have a radiation meter?

chigau@#9:

Nothing about the pilot that I know of. He may not have gotten as exposed – the photographers were leaning out to shoot right down into the core.

Scary Chernobyl story: I talked briefly with one of the security guys, who was a kid, welding on reactor #6 when #4 blew. He said they all heard a thump and then he saw weird dancing lights in his eyes for a while. I don’t know if that’s true – would there be that much radiation? Another Chernobyl story: the only people who sent help were the Japanese. They left a beautiful granite monument near the barracks they lived in, which were the barracks that we also stayed in.

[dailymail]

jrkrideau @#10

The explanation used by that bank worker was that paper money is sometimes marked with radioactive isotopes in order to track criminals. And in the bank they checked for radioactivity all paper money they handled.

When I heard that story I was more surprised by the fact that somebody could get away with borrowing and taking home stuff from their workplace. Apparently that worked just fine in Russia.

There’s no need, IMHO, to worry a lot about the whereabouts of that lens.

After the blast at Chernob’l, the nuclear chain reaction died out quickly (in a matter of milliseconds( if it hadn’t, we wouldn’t be here to bitch about it )).

The poor chap’s lens was, therefore, not exposed to intense neutron flux, which is the way of choice to make the bulk of non-radioactive stuff radioactive.

The lens may have been contaminated on it’s surface, because why not open the window of a helicopter hovering over a burning nuclear reactor? What can possibly go wrong?

Poor chap possibly died because he inhaled stuff (because of opening the window) or just from the γ-rays from some of the very short-lived decay products.

Owlmirror@#4:

I had some Deschutes with my dinner last night! Yummy!